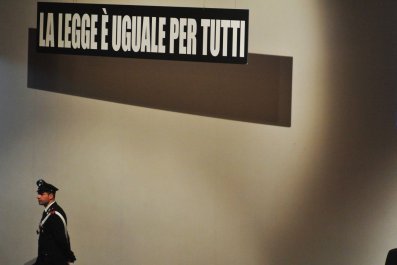

Eight people were sentenced in a Moscow court on Friday, February 21, to between two and a half and four years in prison. They are the first of two groups to be tried in the largest Russian political trial of the past half century. All were charged with attacking policemen during a march on May 6, 2012, the protest that ended Russia's short-lived Snow Revolution. Their case is emblematic of the current Russian crackdown on dissent: The defendants seem to have been chosen almost at random to dissuade people from protesting.

The Snow Revolution began in December 2011, when hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets of Moscow and other Russian cities to protest rigged elections and the seemingly endless presidency of Vladimir Putin. The outpouring shocked both organizers and police; both sides feared violence, chaos and the potential for a large gathering to turn into a mob. Activists and police quickly learned to cooperate, negotiating the placement of temporary metal barriers, the number of metal detectors used by police and their locations, the exact list of banned items (water bottles were a perennial sticking point), and the timing of each march.

They did all of this on the eve of the May 6 protest. Passions had cooled since the winter, when it seemed like the hundreds of thousands in the streets would force Putin to abandon his plan to stay in power perpetually by switching back and forth between the offices of president and prime minister. But in March, Putin declared his re-election for a third, six-year term as president and some of the air seemed to seep out of the protest movement. People still came but in smaller numbers.

On May 6, the eve of Putin's inauguration, the weather was beautiful. People gathered slowly. Many came with children, so if one looked beyond the stern protesters with large banners who led the way, the gathering felt like a leisurely weekend family stroll. To a newcomer, the setup might have looked odd: The protest took place in a cordoned-off area. There could be no casual onlookers, except for the residents of buildings that lined the march route. No one who didn't attended the protest would ever hear its message - unless she logged onto one of the opposition websites or watched the lone independent cable and satellite television channel. A few critics said this arrangement killed the point of the protest, but organizers insisted this was the only way to keep the demonstrations legal. Police permits were issued for the exact route, time and even number of participants. This way no one would get arrested or beaten.

The setup at the beginning of the route looked like it always did: There was a row of metal detectors through which every protester had to pass. But at the end of the route, something looked terribly wrong. Originally people were supposed cross the short but wide small stone bridge and disperse into Bolotnaya Square, drifting either into the park to the right, where the rally would be, or doubling back by way of the park and leaving through one of a couple of different routes. But as the police cordon now stood, protesters coming off the small stone bridge, marching a hundred or more abreast, would have to take a 90-degree turn into the park, walking no more than five or six across. It seemed designed to create a bottleneck, and the march came to a standstill almost immediately after the first protesters came to the narrowing.

When marchers staged a sit-in, the organizers' security did several things: They called their comrades at the stage and scanned the crowd for people with children and led them away through a small opening the police provided. To those they led away from the protest, the security volunteers said, "Something could happen. Better to get away from here."

At first nothing happened. For nearly an hour, some people sat on the pavement, and thousands of other protesters stood more or less still as the police gradually reinforced their ranks. Behind the rows of the Moscow police and riot police stood hundreds of Interior Ministry troops.

Then many things happened in quick succession. Some protesters broke briefly through the cordon in one spot. The police started driving wedges through the crowd. Someone threw a Molotov cocktail, and someone's clothes caught on fire. The fire was put out. Smoke bombs were thrown; one landed at the feet of a riot police officer, and he picked it up and threw it back into the crowd. The police began arresting people, picking men out of the crowd. A series of small riots broke out. By evening, hundreds of people had been detained, the stage had been destroyed and all sound equipment taken. Riot-gear helmets were floating in the channel. Police chased people they believed to be protesters around the neighborhood near Bolotnaya and in a couple of other places in central Moscow. Some of those chases took them into several neighborhood restaurants, where more brawls broke out.

The Snow Revolution, modeled loosely and hopefully on the Czechoslovakian Velvet Revolution of 1989, was over. The Russian crackdown had begun. Within weeks, new laws severely restricted the right to public assembly, instituting fines of up to about $580 and giving law enforcement broad discretion in choosing whom to prosecute. Around the same time, the arrests began.

The hundreds of people rounded up on May 6 had been released within a few days; some weren't even booked. But three weeks later, the police began to arrest some of the protesters on felony charges. The first was Alexandra Dukhanina, a diminutive 18-year-old university student and environmental activist. She was interrogated overnight, faced a judge the following day when she was placed under house arrest and banned from using any means of electronic communication. She was arraigned under two articles of the Russian Criminal Code, carrying a maximum combined sentence of 13 years. The indictment stated that Dukhanina had thrown rocks and bottles at police.

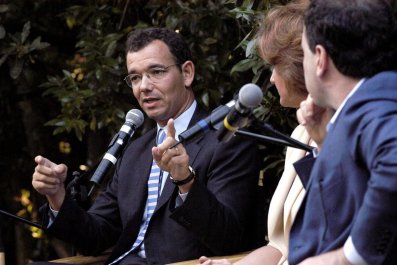

Two weeks later, five young men were arrested in their homes in Moscow. They included rank-and-file activists and at least one man who had never been politically active but had decided to attend the May 6 protest to see, essentially, what all the fuss was about. When it became clear that anyone who had been detained on May 6 who could be identified in any of the many hours of video footage from that day was likely to be arrested, dozens of people fled the country. In the end, charges were filed against 29 people, two of whom were at large, believed to be living abroad. Only one person-Sergei Udaltsov-is a well-known leader in the protest movement. The rest are names known only to their friends and families - and now to a small group of Russians who have been following the biggest political trial of their generation.

One man, who had a history of mental illness, was sentenced to forced psychiatric treatment. Two men pleaded guilty and, in exchange for testifying against some of the others, were given sentences of two and a half and four and a half years behind bars, respectively. The first trial, of a group of 10 men and two women, began March 5, 2013, and continued daily, with few breaks, until this month. Four of the defendants were amnestied in December under the same law that secured the release of the Pussy Riot prisoners. The Bolotnaya prisoners had been behind bars for more than a year by that point. On February 21, 2014 all eight were found guilty, and on February 24, their sentences were announced: Seven people will serve between two and a half and four years in prison colonies each; the lone woman in the group, Dukhanina, was given three years three months, suspended. The second group of 10 are still awaiting trial.

Over the past 11 months, the people convicted on Friday spent nearly every weekday in court, all but the two women defendants crammed into a Plexiglas aquarium too small for them to sit down or take notes. A long line of police officers testified as victims or witnesses, more often than not becoming confused while telling their story, failing to identify a defendant or answer the simplest questions, such as why, if the witness claims to have been attacked by a defendant while trying to apprehend him, video footage shows the defendant being detained by someone else.

"At first I thought that this whole case is some sort of crazy mistake and misunderstanding," said Dukhanina in her closing statement. "But now that I have listened to the prosecution's speeches and heard the kind of sentences they are asking for, I have realized that they are taking their revenge on us. They are punishing us for having been there and having seen what really happened. Having seen who caused the human crush, having seen them beating people, having seen the unjustifiable cruelty. They are punishing us for not caving in and not pleading guilty to crimes we didn't commit."

On Monday, while the sentences were read, 234 people-roughly half of the number who came out to support the defendants-were detained in front of the courthouse, most of them for standing silently. Others, like Nadezhda Tolokonnikova of Pussy Riot were arrested for shouting out "svoboda"-freedom.

That evening, over 400 people were arrested in the center of Moscow at an unsanctioned protest against the verdict; all were charged with violating the laws on public assembly and some with resisting police, which may mean jail time for yet another group of protesters. Some people were in fact arrested and booked twice in on Monday-including Pussy Riot's Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina, who have been working to draw attention to the Bolotnaya Square case since their own release from prison two months ago.