Private Morales was immersed in morning prayers when an officer rushed him outside and into a convoy of four pickup trucks with no license plates. The army had received a tip about a drug and weapons cache inside a house in Nueva Suyapa, a gang-filled neighborhood in Honduras's capital city, Tegucigalpa.

Morales and more than two dozen other soldiers sped away, moving islands of bodies in ski masks snaking through morning rush-hour traffic. Finally, with the target in sight, Morales, who requested that his name be kept confidential to protect both him and his family, jumped out of the truck and dashed off to his look-out position. There, the 22-year-old stood alert, his delicate hands gripping his rifle, his long eyelashes batting against the dusty wind. Tucked under his unit's logo on his left sleeve was an "O+" patch - his blood type.

An hour went by and the team, which included two sniffer dogs and three public prosecutors carrying copies of the penal code, found neither drugs nor weapons in the house. It is "very likely" that the suspects were tipped off, said one of the officers in charge of the mission. "They have more informants than all of us."

As the soldiers were preparing to get back onto the trucks and return to their barracks, balaclavas damp with sweat under the hot Caribbean sun, a brooding young man with thick eyebrows approached an officer and pointed to a house down the ravine. He said the men living there stored drugs and frequently terrorized residents.

The military squad walked quietly down the unpaved road in a single file. A couple of soldiers pulled aside the dirty fabric serving as a door and entered the single-room, dirt-floored dwelling while the public prosecutor asked a woman inside the house if she was the owner. A prepubescent boy walked around with a towel wrapped around his thin waist, otherwise naked, looking dazed.

The soldiers turned the house upside down, emptying trash bins and searching inside an old oven stuffed with clothes. They found a package resembling a drug parcel and cut it open, struggling through layers of newspaper with a dull knife. Through the gash, nails spilled out onto the floor. A soldier, looking disappointed, continued searching under a pile of rocks outside.

The search turned up nothing, but one of the officers predicted that the snitch who had led them to this house would get picado - chopped up - in the next couple of weeks for daring to speak to them. Morales muttered that he was glad he was wearing a ski mask and was thus unrecognizable, as his family lives nearby.

In the middle of the swarm of soldiers, a toddler and a 5-year-old boy ran around each other in circles, shooting imaginary bullets from plastic assault rifles and piercing the tense air with their sound effects.

Bodies Hanging Off Bridges

For decades, Mexico has been the drug war's main battleground, but the police and army there have slowly been wearing down the criminal syndicates, forcing them to develop new transport routes. Drug traffickers, adaptable and enduring, have been shifting toward Central America. According to the U.S. State Department, "as much as 87 percent of all cocaine smuggling flights departing South America first land in Honduras." In fact, analysts and military officials have begun calling the current situation in Honduras a "Mexicanization," pointing to the influx of Mexican drug kingpins, the increasingly grotesque crime scenes - including hacked-up victims and bodies hanging off bridges - and the growing presence of the military on the streets. The country now has one of the highest homicide rates in the world and one of the poorest scores for corruption from Transparency International, which studies government officials.

The war on drugs in this country of 8.5 million people is leaving a trail of death and trauma, aggravated by weak and corrupt government institutions and an employment crisis affecting nearly 50 percent of working-age Hondurans.

The military is involved in this sordid war because the Honduran police are outgunned and corrupt. "Those people are very clever, and they have a lot of money and ways of getting their way," says Miguel Facussé, one of the wealthiest, most powerful businessmen in the country, referring to drug traffickers. At least one of Facussé's airstrips, which he uses to reach his properties near the Caribbean coast, has been used by drug traffickers. He told Newsweek that this was done without his permission or knowledge and said that his private security guards had probably been bought off.

But even soldiers are not much of a deterrent to the drug cartels, which are, "in many cases, equally or better equipped than the Honduran Armed Forces, [and represent] a threat to the existence of the state," says a recently passed law that created a new military police unit to fight organized crime.

And as Honduras descends into chaos, its once close relationship with the United States, a strong ally that has been expanding its military presence here in recent years, is beginning to fray. "It is a double standard: while we are providing the deaths and fighting with scant resources of our own, for North America the drug issue is merely a health matter," said newly elected, conservative president Juan Orlando Hernández during his inaugural address in January. "For Hondurans and the rest of our Central American brothers, it is a matter of life and death."

The Lily Pad Strategy

"Nothing gets done without the U.S. ambassador's seal of approval," is accepted as gospel in Tegucigalpa.

Ties between Honduras and the United States run deep. In the 1980s, the U.S. based its clandestine war against the Sandinista government in Nicaragua and the leftist rebels in El Salvador out of Honduras. It set up the Soto Cano Air Base, a large military outpost from which it runs its regional operations. In recent years, the number of U.S. bases or installations in Honduras has grown considerably, albeit quietly, according to military analysts. David Vine, a professor of anthropology at American University who has written extensively about U.S. military bases abroad, has counted 13. "A million dollars here, $2 million there, $500,000 there for a firing range," he says, explaining that these expenditures are part of a "lily pad strategy," in which the U.S. dots the globe with small facilities in order to maintain its global presence while using minimal resources.

But those ties are loosening. Honduran military officials, in recent private talks with Newsweek, revealed profound resentment toward American involvement and interference in their battles with the drug cartels. "The interrelation has decreased with each passing day," says Fredy Santiago Díaz Zelaya, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the Honduran Armed Forces. "Honduras has its own capacity, and we will depend less every day on other countries to do our job."

In November 2011, the Honduran Congress - then helmed by now-president Hernández - approved an emergency decree calling on the military to carry out police duties, including taking on organized crime directly. Morales joined the army shortly after that, and since then, his life has blurred into one big olive green-colored, drug-hunting nightmare.

A Cloud of Gunfire Smoke

A self-described "bad student," Morales says he loved watching action shows growing up and decided early on that he wanted to emulate his beloved TV icons. He quit middle school to take on odd jobs painting houses until he made his way into the army.

He admits that he does not know much about the war on drugs, but says Americans who consume drugs are just as oblivious to the mayhem they leave behind. "What they are doing, consuming drugs, sometimes it doesn't harm them as much, but those drugs carry many consequences," says Morales. "Maybe along the way they leave behind innocent deaths, maybe incarcerations."

"The road is full of injustice for, maybe, a brief moment of fun."

The slum where Morales grew up is one of the most dangerous in Tegucigalpa. It is a labyrinth of steep dirt roads and single-story houses made of exposed bricks and cinder block that has made headlines for the many massacres carried out there; last year, several men were slain in broad daylight by people in a pickup truck. Witnesses told local reporters that a cloud of smoke, most likely from the gunfire, could be seen from afar.

Some of the houses seem to be trying to skulk behind tall, concrete walls. Others can't hide their decay behind thin, metal bars on windows.

Every three weeks or so, Morales gets released from his barracks to spend time with his mother and siblings. As he hops on a public bus down the road from the military quarters, his brown crew-cut gelled back, a collared T-shirt tucked into his snug jeans, Morales looks youthful - two deep dimples puncture his cheeks when he smiles, a couple of pimples frame his lips.

His mother's house is stark but impeccably clean (their father left when Morales was young and the family recoils when asked about him). A hanging sheet separates his bedroom from the living room, which is barely big enough for an old cloth-covered beige couch and two armchairs. A single light bulb illuminates the religious memorabilia on the walls and the soccer trophies on the shelf.

The shower is outside, a roofless, doorless area enclosed by brick and a yellow plastic tarp. Morales's oldest brother, who spent time in the United States working at a supermarket stockroom, lives in a room behind the house with his wife and daughter.

For a few minutes, Morales plays with his daughter, in the living room as his mother, who asked to remain anonymous, moves around the tiny kitchen, seasoning a pot of rice and heating up a stack of tortillas.

She remembers more desperate times for her family, when she had to send her young children out into the streets to sell bags of water. But what her family has gained in financial stability - Morales's mother started out as a janitor but worked her way up the chain to become a clerk at the juvenile court, doubling her salary - she believes the country has taken away in personal safety.

She says thieves have broken into the house several times. Once, they went through the neatly folded clothes, picked out the best pieces and packed them into a suitcase. They even took a few pairs of shoes. The police told her "that if I didn't see them or know who they were, it was a waste of time" to file a complaint.

It is a story that repeats itself across Honduras: crimes small and large everywhere, but 80 percent of them go unreported, according to the National Human Rights Commission. The homicide rate, which hit a high of 86.5 homicides per 100,000 residents in 2011, has decreased slightly but the number of massacres (two or more deaths in a single crime scene) has increased, says Julieta Castellanos, the rector of the National Autonomous University of Honduras.

In 2011, Congress passed a law banning two men from traveling on a motorcycle after several prominent Hondurans were gunned down by passengers on scooters. But like many laws in this country, it is little more than a meek suggestion. In 2012, the Peace Corps paused its operations in Honduras in order to conduct an assessment of safety and security conditions. In September of that year, it suspended its program in the country.

Congress approved a law in December forcing telephone companies to block cellular signals inside prisons, where hits are masterminded, extortion calls are made and kidnappings are coordinated. In the latest effort to reduce crime, the government announced earlier this month that the sale of alcohol would be prohibited on Sunday afternoons and nights, when the most murders occur.

An already overwhelming sense of danger is exacerbated by a police force widely perceived to be corrupt and often criminal. Last year, the Associated Press reported on death squad-style killings in Tegucigalpa carried out by the police. "Even the country's top police chief has been charged with being complicit," wrote Alberto Arce, the reporter who investigated the story.

Under the guise of a "social-cleansing" policy, the police have been taking people associated with gangs into custody, sometimes never to be seen again. Often, Arce wrote, police pick up their targets in vehicles with no plates - much like the army trucks.

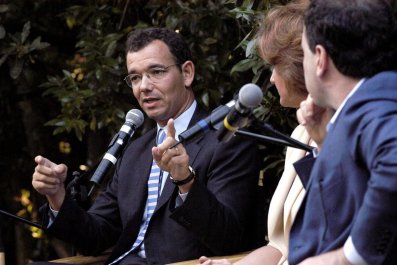

In 2012, former president Porfirio Lobo Sosa created the Public Security Reform Commission, tasked with pushing out corrupt policemen, public prosecutors and judges. It was made up of several international experts, including Adam Blackwell, the Organization of American States's secretary for multidimensional security.

But last month, the Honduran Congress dissolved the commission, as reports emerged that several dozen police officials who had been under investigation had been honorably discharged.

There was outrage but no surprise. Honduras, is, after all, a country where crimes are rarely prosecuted and a "blame the victim" mentality reigns supreme. Women are killed because they cavort with cartel operatives or sell drugs, lawyers are murdered because they represent drug traffickers and journalists are slain because they have links to, or have written about, people involved in the drug trade, says a spokesman for the armed forces.

Castellanos knows about police brutality too well. In 2011, her 22-year-old son and a friend were driving away from a party when they ignored a group of police demanding that they stop. Shortly after, the two young men were found dead, their bodies riddled with bullets. Within days, Castellanos was able to prove that the police had killed her son. In December, four policemen were convicted of murder and sentenced to 66 years in prison.

Her case was extraordinary, for only a handful of murders are properly investigated or prosecuted. Why was this case different? Castellanos says she was able to "snatch away the investigation monopoly" from the police, allowing a team of friends, colleagues and investigators to gather and safeguard evidence, interview witnesses and piece the night together.

The repercussions of this institutional corruption and abuse have reverberated back to Washington. When the United States reinstated aid to Honduras after it had briefly suspended it following a military coup in 2009, it unleashed controversy within the U.S. Capitol. In June, a group of 21 U.S. senators sent a letter to Secretary of State John Kerry, expressing their "concern regarding the grave human rights situation and deterioration of the rule of law" and urging him to review aid to Honduras, which last year included $16 million for police units.

"If we do not send a strong message to the government of Honduras, then they are going to think we are a cheap date," said James P. McGovern, co-chairman of the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission during a July congressional hearing. "They are going to think the money will keep coming no matter what they do."

The 2014 appropriations bill included stronger restrictions on U.S. assistance to Honduras, including withholding 35 percent of the funds allocated for the police and military until the Secretary of State certifies that corrupt officials are being prosecuted, freedom of expression and due process are protected and human rights conditions are being met.

A Soldier on Every Corner

ith pomp and ceremony, Juan Orlando Hernández was sworn in as president last month at the national stadium. Feathers protruded from military hats, decorative red smoke enveloped the assembled army units and a young, indigenous girl read a poem to a tearful Hernández. The climax of the event came when Hernández launched Operation Morazán, the latest strategy to tackle petty and organized crime. "On every corner, at every fork, there has to be a soldier of the armed forces and a policeman who has gone through the process of certification," said Hernández during a campaign speech in Olanchito, a town near the Caribbean Sea.

The operation, named after Francisco Morazán, one of the most widely respected 19th century liberal leaders in the region and former president of the Federal Republic of Central America, is coordinating the army, police, and public prosecutor's office to work together during special operations, like the one Morales was recently assigned to in Nueva Suyapa.

Central to Operation Morazán and the Honduran fight against drugs is the Military Police of Public Order, a revamped elite military unit which Hernández launched last year during his presidential campaign. Like Morales, the 1,000 or so military police recruits (two of them are women) receive military training but operate as police.

Hernández's growing dependence on the army has become highly controversial in a country still haunted by a history of military brutality. A wave of political uprisings and civil wars swept over Central America during the 1980s, ripping through Nicaragua, Guatemala and El Salvador. In Honduras, the military - which had close ties to the CIA - tortured and executed guerrilla sympathizers. Hundreds of dissidents disappeared.

Now, analysts and activists are calling the military surge on the streets a step backward and warn of impending human rights violations. In the military quarters in Tegucigalpa, Morales recently attended a class on human rights and due process. The teacher, public prosecutor Ricardo Núñez, spoke about these issues in broad terms and then showed a staged video in which two guards viciously beat a supposed delinquent.

After class, Morales hopped on a military truck and went, along with several dozen other military police soldiers to a checkpoint at Flor de Campo, a crime-ridden neighborhood of about 60,000 residents. There, he and his fellow soldiers stopped and boarded public buses, plucked young men out and had them lean against a wall, arms and legs spread, while he patted them down. Then, he went through their bags and asked to see their IDs.

Officials involved in Operation Morazán, of course, appear optimistic about the potential of this newest offensive. But privately, they express skepticism about their mission because of its dependence on the police.

Santos Torres Galeas, a military police officer, says "the police, from top to bottom," would have to be replaced for there to be progress.

Five Security Guards for Every Policeman

Morales's younger brother, a quiet boy who avoids eye contact, has set up a makeshift pulperia - small convenience store - by the side of the road near his mother's house. He sits next to the rickety table during the day, waiting for children to come by and purchase candy or, his best-seller, oranges. It isn't much, but it helps supplement his family's income.

Despite the rampant crime in Honduras, the most pressing worry is the economic crisis. A 2013 poll revealed that 57.5 percent of Hondurans believe job creation should be the new administration's priority, followed by 17.1 percent who cited fighting crime.

And it is no surprise, with nearly 50 percent of those looking for jobs unemployed or underemployed. A drive around Tegucigalpa provides haunting evidence of this: hordes of young men loiter, observe traffic or wash car windshields during much of the day and part of the night.

The 2009 global recession hit Honduras hard. External demand fell and remittances, which Honduras is heavily dependent on, dropped. Rising crime, too, has fed into the deteriorating economy. The World Economic Forum's 2013-2014 Global Competitiveness Report ranked Honduras last of 148 countries for business costs of crime and violence.

Private security is one of the few robust industries here. According to a 2013 United Nations report, there are close to five private security guards for every police officer in Honduras. These mercenaries are highly visible throughout Tegucigalpa: in the entrance to shopping malls, universities and restaurants, and in the middle of public roads which have been gated by local residents.

Analysts say another sign of financial upheaval was the military coup that deposed former president Manuel Zelaya in 2009. Average annual gross domestic product growth in Honduras during the two years prior to the coup was 5.7 percent; since the coup, it has slumped to 3.5 percent. "In the two years after the coup, Honduras had the most rapid rise in inequality in Latin America and now stands as the country with the most unequal distribution of income in the region," said a 2013 report from the Center for Economic and Policy Research, which indicated that all real income gains went to the wealthiest 10 percent of Hondurans.

Seven out of 10 Hondurans currently live in poverty; 46 percent live in extreme poverty. In such dire circumstances, a stable job is increasingly attractive, even if it means you are likely to be pulled out of church and thrust into a gun battle with drug traffickers. Many of these soldiers come from working class or peasant families. Recruits must be at least 18 years old, have completed sixth grade, not have tattoos or piercings, and have a clean criminal record. Young soldiers earn around $280 a month, well below the average minimum wage, $380, but for them, stability trumps a low salary.

Because he is part of the military police and is therefore exposed to more risk, Morales earns approximately $470 a month. He spends some of that on clothes for himself, gifts for his daughter, food for his family, his cellphone - which he uses frequently to listen to music, browse Facebook and text his friends - and his girlfriend. The young soldier boasts that he saves, on average, $100 per month.

His mother would like her son to stay in the army, become a colonel and have a stable life near her. But Morales has other plans. He says he wants to move to the United States.