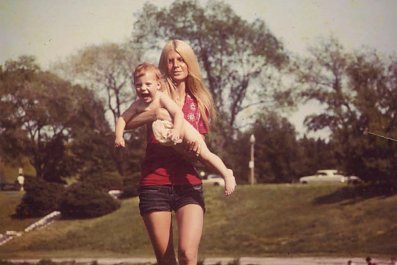

In November 2012, 2-year-old Sofia Jarvis started to wheeze uncontrollably. As Sofia gasped for air, her terrified mother rushed her to the doctor. The little girl with bright orange curls ended up spending 24 hours in intensive care before doctors proclaimed her back to normal. They sent her back to her home in Berkeley, Calif., with some medication and a simple diagnosis: asthma.

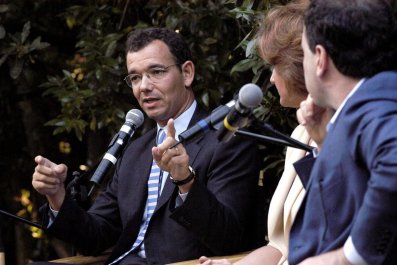

A few days later, Sofia was reaching into her toy box when her arm stopped working. "I saw her arm stop mid-motion," her mother, Jessica Tomei, told Newsweek. Today, at the age of 4, Sofia still cannot move her arm, although she remains upbeat. She calls it by an endearing nickname: Lefty.

Between August 2012 and July 2013, sudden paralysis beset five children in California: Sofia and four others who fared even worse - one child lost control of all four limbs. On the surface, these cases looked a lot like polio. But the last time poliovirus claimed an American victim was in 1979, and all of these children had been vaccinated. Whatever they had was something else - something rare and possibly new.

A disease is considered "rare" if fewer than 200,000 people have it. As a class, rare diseases are actually fairly common; many universities and public health organizations have teams that specialize in researching rare diseases as a group, and the National Institutes of Health estimates more than 25 million Americans suffer from one of the 6,800 known rare diseases.

And those are just the known diseases - there are also many unknown illnesses that can afflict the human body. Mysterious pathogens, borne by food, feces or saliva, can enter the body and latch on to cells within. Often they're harmless. But for some people - with the wrong genetic disposition, perhaps - they're not. In those cases, even if doctors get lucky by locating the problem (and possibly naming a new disease), there may not be a treatment, says Emmanuelle Waubant, a University of California, San Francisco neurologist, who worked on the five California cases. Sometimes, she told Newsweek, "the recovery is poor no matter what you do."

That has been the case for Sofia and the other children described in a recent study by Waubant and Keith Van Haren, a neurologist at Stanford University: to date, no therapies have helped with the paralysis of any of the five children.

The first step toward a treatment would be to identify the cause. For two of the children, tests revealed the cause to be enterovirus-68, or EV68, a distant cousin of the poliovirus under the same viral genus, Enterovirus. For Sofia and two other children, the disease remains a mystery; according to Waubant, early treatments administered to the children obscured the reliability of the tests, leaving her team in the dark.

Dr. Gregory M. Enns, director of the Biochemical Genetics Program at Stanford University, tells Newsweek that understanding why viruses latch onto some people's cells and not others is a million-dollar research question. For virologists, sleuthing for the root of mystery diseases is like wandering a maze in the dark. It's a matter of guessing and checking, swabbing samples and testing for a match. For the three children in the group who have no diagnosis, the possibility of finding the viral culprit is bleak.

"I don't think we will ever find the precise virus for these three patients as it has been too long since they had their acute infection," Waubant says. Viruses attack and flee; it's important to take samples right away.

One theory is that it could be an unknown enterovirus type. "In the past decade, newly identified strains of enterovirus have been linked to polio-like outbreaks among children in Asia and Australia," Van Haren said in a statement.

Enterovirus outbreaks have happened in the U.S. in the past; the worst was in the early and mid-20th century, when the polio epidemic spread through the country, crippling 35,000 people annually at its peak. The disease began to abate only in 1962, when Albert Sabin's vaccine was licensed. Polio began to dissipate almost immediately, though it took three decades before the virus was eradicated completely in the U.S. But at the same time, a new enterovirus strain appeared. At the end of 1962, four wheezing children were admitted to a California hospital. Using X-rays, doctors could see their lungs were full of mucus, as though they had parainfluenza or bronchiolitis. But lab tests came up negative for these diseases, and it was clear that this was not polio.

Research doctors from all over the state came to investigate. They swabbed the children's throats and cultured them in the kidney cells of rhesus monkeys. After about a week, the monkey cells started to change shape, from small and elongated to large and circular. The cause, they determined, was a previously unknown virus.

Later, this virus was named enterovirus-68 - the same bug that has infected two of these children decades later. Since 1962, only isolated cases of EV68 have reappeared in the medical literature. Until now, the most recent had been an outbreak in a hospital in the Philippines in 2008 and 2009, when 21 children were found to be infected, researchers wrote in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Two died. But no one with EV68 had been known to suffer paralysis, until now.

Sofia's mother says the rest of her family, including her husband, Jeff Jarvis, and her two boys, are healthy and always have been. It's possible, the doctors say, that they all were exposed to the mystery virus. Why Sofia was affected and the others weren't remains a mystery.

A bigger puzzle, though, is why the EV68 virus attacked two children's spinal cords and paralyzed them when enteroviruses typically produce mild symptoms or none at all.

"It is likely that most patients with EV68 have a benign upper respiratory infection, and only a small fraction of these may develop polio-like disease," Waubant says. "It could also be that the virus genes have some mutation making it more neurotropic" - that is, more likely to attack nerve tissue.

In the meantime, Sofia's parents have tried a number of therapies to stimulate her arm. "We put electrodes on her every day," Tomei says. They play Wii Fit, and they've heard Indian polio victims have had success with acupuncture. Sofia, a precocious 4-year-old, understands that her arm is paralyzed and may not recover. But she's determined to make the best of the experience: Sofia wants to be a neurosurgeon when she grows up.