The Eastern District of North Carolina is officially classified as a "judicial emergency."

It takes years for cases to move through the court, where a vacant seat on the bench has created one of the worst case backlogs in the country. The court's open seat has gone unfilled for eight years, the longest district court vacancy in the country.

To fix the problem, Republican Senator Richard Burr of North Carolina wrote to President Obama in 2009, suggesting he appoint Jennifer May-Parker, a prosecutor from his home state, to fill the long-empty seat. It took a while, but in June 2013 Obama nominated her.

So everyone was surprised when Burr decided to block the very nomination he once recommended.

With Republicans holding the House of Representatives, appointing judges through the Democratic majority in the Senate should be one of the few ways the president can accomplish something in his bogged-down second term. But the May-Parker debacle stands out as a particularly egregious example of obstruction keeping the Obama administration from filling dozens of vacancies across the country despite a years-long judicial vacancy crisis.

The Senate, the clearing house for the president's judicial nominations, wasn't supposed to be like this anymore. Last November Senate Democrats went "nuclear," as they call it, changing the filibuster rules to eliminate the 60-member supermajority necessary to confirm judicial and executive appointments.

But the gridlock over the president's judicial nominees persists.

And it's not just North Carolina. Across the country, the federal judiciary has 96 vacancies: 80 in the federal district courts and 16 in the appellate courts. Thirty-nine are considered judicial emergencies.

According to an upcoming analysis by the Brennan Center for Justice, there were just 35 trial court vacancies at the same point in President George W. Bush's presidency and about 60 at the same point in President Bill Clinton's. There are 32 judicial nominations waiting for a final vote on the Senate floor.

"Our courts are in dire need of having these vacancies filled," said Alicia Bannon, an expert on judicial selection at the Brennan Center. "Ordinary citizens and businesses rely on our courts to be fully staffed."

But Democrats have another reason to move on judicial appointments this year: The midterm elections in November, when Republicans may well win back control of the Senate and dash Obama's chances of shaping the judiciary for the rest of his presidency. With the clock running, Democrats must decide how hard they will fight to put more judges on the bench, or let Republicans block them until the buzzer goes off.

"This is a really important moment in the history of judicial nominations," said Michelle Schwartz, who works on judicial selection issues at the left-leaning Alliance for Justice. "It does present this great chance to make a dent on the bench and get some really good people on the bench."

The courts play an important role in each party's policy agenda, the place where partisan battles on everything from environmental regulations to the Affordable Care Act see their day in court. If a minority party doesn't like what the majority does in Congress, they can turn to the courts to overturn what they could not stop with elections. And that means both parties take these nominations immensely seriously.

Court advocates have been raising alarm bells about the vacancy crisis for years, and it's not all the GOP's fault. President Obama was slow to send nominations to the Senate early in his presidency. It's also true that Republicans are not the first party to block judicial nominees. And while many Republicans are blocking nominees in their states, like Burr, others deserve credit for allowing them through.

But it is the GOP that, since Obama took office, has stalled and filibustered at an unprecedented rate. For instance, of the 23 district court nominees ever filibustered, 20 were Obama picks.

"In previous cases it was the minority party filibustering nominees they judged were not mainstream," conservative scholar Norm Ornstein said last November. "There's no case even being made that these nominees aren't qualified. We've never seen that before."

Today, Republicans argue that the tables have turned - that filibuster reform has taken away their minority rights to weigh in on nominations.

"By voting to invoke the nuclear option, the majority stripped the minority of any ability to stop any nominee from being confirmed on the floor," said Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa, the top Republican on the Judiciary Committee, at a confirmation hearing this month. "The bottom line is that the majority voted to cut the minority out of the process."

Certainly, removing the filibuster was a necessary step for Democrats hoping to move many nominations forward. But even without the filibuster, Republicans have other tools at their disposal to delay the process. And they are using them.

This brings us back to Burr and May-Parker. The White House's efforts to fill the bench are being stymied by the "blue slip" process, a Senate Judiciary Committee tradition that today gives senators considerable power over judicial nominees in their home states. When a nominee is referred to the committee, the two senators from that state are notified on a blue slip of paper. To signify their support for the nominee, they return the slip.

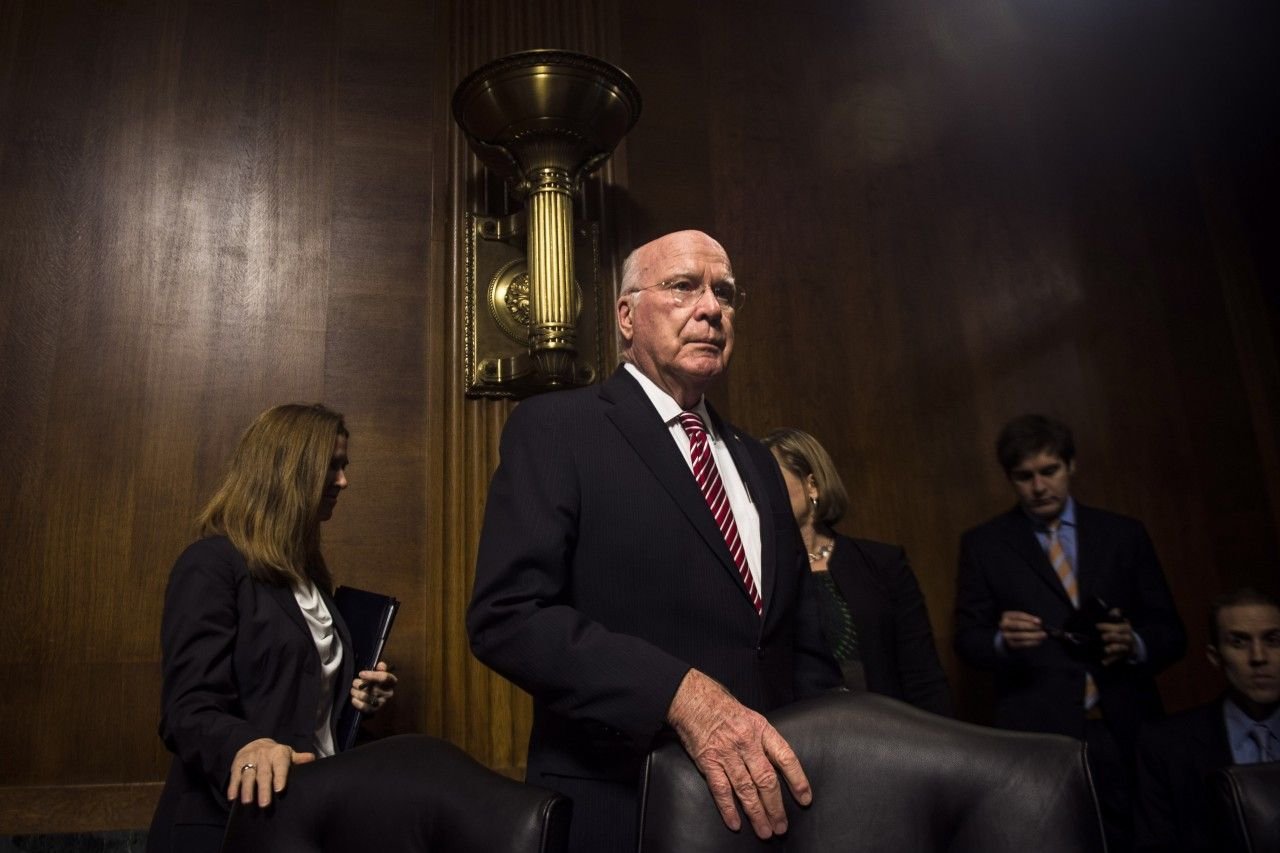

It's up to the chair of the committee how to deal with a blue slip that is not returned. The current chair, Patrick Leahy of Vermont, has upheld the tradition strictly, allowing Republican senators essentially to veto the president's picks, as Burr has done by not returning the blue slip. It's no coincidence that most of the vacancies without nominees are in states with at least one Republican senator.

Leahy, an institutionalist who believes in rights for senators in the minority, has said he sees no reason to change his approach to blue slips unless he believes the tradition is being abused. The chairman can boast a few successes recently, holding confirmation hearings for six judges from Arizona, one from Florida and one from South Carolina after working with Republican senators from those states to get the blue slips returned.

"The question becomes, When will [Leahy] conclude that Republican senators are abusing the rule?" said Russell Wheeler, an expert on the court system at the Brookings Institution. "The reality may sink in that if Obama doesn't get a good number of confirmations this year, it will be his last shot. If Democrats want to make an imprint on the judiciary, this is the year to do it."

If Leahy decides to change his approach, his committee could send a great number of nominees to the floor. But whether they would ultimately be confirmed is another story. Because in the Senate, even if two procedural hurdles are demolished, more are lurking around the corner.

The Senate rules provide ample chances for the minority to slow business in the Senate. In the golden years, when historians remember the upper chamber as a place of cross-aisle friendships and collaborations, Senate procedure did not create gridlock. But today, the minority can throw the rule book at the majority and bring the chamber to a grinding halt.

"The Senate is really in many ways a broken institution that is trying to govern in 2014 on notions of comity and unanimous consent that seem quite unrealistic these days," Wheeler said. "And I don't see what changes. That's the really sad part about it."

Chief among these is the time it takes for a nominee to get a vote on the floor. Back in the good old days, senators would skip over procedural votes and debate time and move straight to a vote on an appointment with "unanimous consent."

But nothing is unanimous anymore. Instead, the majority must stop debate time by invoking cloture (this used to require 60 votes, but post-filibuster reform only requires 51). Then, the minority can insist on holding up a final vote for two hours for district court appointments and 30 hours for appellate court appointments. If you dive deeper into the rule book, there are yet more procedural hoops Republicans make the Democrats jump through.

It can take days and several votes just to confirm a single nominee. Multiply that by the number of vacancies, weigh it against all the other business the Senate must attend to, and it becomes clear that without more cooperation - or yet more rule changes initiated - Democrats won't get many nominees through.

"I think it's an attempt to slow things down, and I think that it is an attempt to leave these seats open, quite frankly," Schwartz said. "The slower that you make things and the less opportunity that you give to the president to fill these seats, the more left vacant. They've got to be hoping that someday we get a Republican president and that president gets to fill these seats if we've left a lot of them vacant.

"[It's] just the ongoing obstruction for obstruction's sake, where you are gumming up the works and saying, 'If you want to get these people confirmed, then we are going to prevent you from doing everything else,' " she continued. "You are going to have to use up all the time of the Senate on getting these confirmations through."