Becky McKinnon, a muscular 33-year-old blonde, was at the Gold's Gym in Bountiful, Utah, and feeling hungover at her Saturday morning yoga class. That is not in itself remarkable, except that McKinnon's Mormon roots run deep (her family converted in the 1840s) like most everyone in these parts. Eleven miles north of the The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) headquarters in Salt Lake City, Bountiful is about as Mormon as an Osmond Christmas special and yoga, like alcohol, is not generally part of the mix.

After struggling through a Chaturanga, she crouched into child's pose and stayed there until Shavasana. Her 56-year-old boyfriend, Timmy Chou, waited by the leg-press machines outside the yoga room, talking with a clean-shaven man who seemed uncomfortable.

"It's been too long," said the gentleman, offering a handshake. "Let's keep in touch."

"Yes, let's," Chou said, slipping a business card into his palm instead. "Merry Christmas."

The man, who had recognized Chou from LDS church meetings, looked down at the card. His polite smile drooped into an expression of shock. "Are you questioning the Mormon church?" the card read, "Thinking about leaving the Mormon church? Already left the Mormon church? YOU DON'T HAVE TO DO IT ALONE." It listed six websites, including PostMormon.org, an online community for ex-Mormons with 9,275 registered members.

As a Mormon missionary, Chou converted dozens of people in the Hawaiian Islands. Now, as self-proclaimed "PostMo" in the Mormon world capital, he uses his recruitment training to get people out.

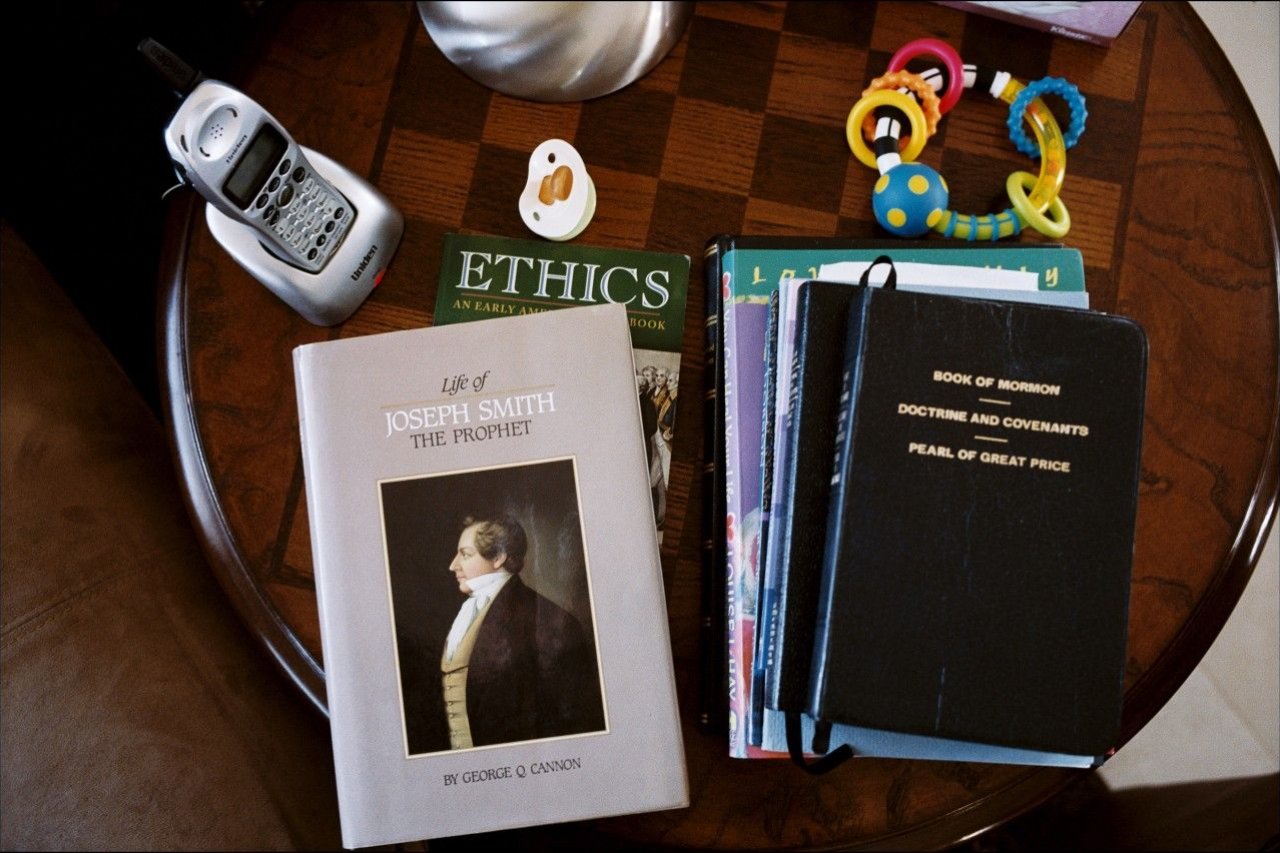

McKinnon, an engineer for the Federal Aviation Administration, was doing her own brand of evangelizing by slipping an identical card into every locker in the women's locker room. She recently printed 10,000 copies. When they travel, McKinnon and Chou like to stay at Mormon-owned Marriott hotels. They seize the opportunity to spread the word (if not The Word) by leaving a card in The Book of Mormon that's reportedly placed in every room. It's a technique McKinnon learned as a child. Church members call it leaving "pass-along cards."

"Before we got [our own] cards, Timmy would just write, 'Lies! All Lies!' in the cover [of The Book of Mormon], with a link to our website," McKinnon whispered to me in the gym parking lot, trying to remain inconspicuous in a crowd of Mormons with gym bags.

McKinnon and Chou are among eight administrators of a support group for ex-Mormons that meets twice a week at Kafeneio, a coffeehouse in downtown Salt Lake City. The "SLC PostMos," as they call themselves, have 792 members on Meetup and 577 more in a closed-to-the-public Facebook group. They throw parties at bars and host monthly "heathen lunches" at Olive Garden. The PostMos are a band of outsiders in Utah, where roughly 62 percent of the population is Mormon, roughly 77 percent of the state government is Mormon, and Mormon culture permeates almost every aspect of daily life. They have created a subculture so cohesive that, during the week before Christmas, there was an ex-LDS event in the Salt Lake Metro area every day. Some former adherents act like soldiers for an ex-Mormon liberation army, seeking out the doubters within the church, extracting them, and bringing them to more tolerant territory. They plaster their calling cards all over, even slipping them, as McKinnon did, "in the Mitt Romney books at the grocery store."

"People intuitively know that first and foremost their primary identity is a nameless soldier in the army of Mormonism," said Chou, a businessman (he is, among other things, chief executive officer of BluApple, which makes vegetable preservers) and rock climber with a professorial disposition. He stressed the importance of being "proactive" in a state where many are scared to voice their doubts about the church, which has its a disciplinary council that can order an excommunication of any church member who strays, a modern-day scarlet letter that cuts a person off from all active LDS members.

"We see that people really are trapped in [LDS]," McKinnon whispered. "What we're here to do is to catch these people when they fall."

Doubt Is Just a Click Away

Deanna Rosen, a 61-year-old social worker with a resemblance to Kathy Bates, has been counseling the ex-LDS population in Salt Lake City for 12 years. Rosen, who speaks with a bluntness that's much more New York City than Beehive State, did not come here to specialize in ex-Mormon issues. As soon as she moved to Utah from Texas, though, the doubters found their way to her earth-toned office. Rosen is open about her Jewish faith, which may have been a beacon for Mormons ashamed to discuss their doubts with faith-promoting counselors at LDS Family Services. Though Rosen insisted, "There isn't a counselor in Utah who doesn't get Mormons with questions," Rosen insists, adding that the "gateway drug" out of Mormonism is Google.

Rosen's patients find historical information online - like the fact that Joseph Smith, the church's founding prophet, had dozens of wives, some of them as young as 14. (While the church now teaches that polygamy was practiced in the 1840s "in accordance with a revelation to Joseph Smith," his polygamy is not mentioned.) She says the "Google Effect" is particularly powerful because the church interprets its gospel literally, as historical fact.

Chou's "downward spiral" away from the church is a textbook example of that. He was 50 years old when he stumbled upon a Salt Lake Tribune article about DNA evidence that indicated Native American ancestors came here from Asia. According to The Book of Mormon, "the principal ancestors of the American Indians," were a group of Israelites who came to the Americas circa 600 B.C. (In 2006, the church quietly changed this language to "among the ancestors of the American Indians.") Chou, who is half-Chinese, spent most of his life reading LDS-approved literature, watching LDS-approved films and getting his news from LDS radio. After discovering the Tribune article, he began to seek objective sources. "It sounds crazy to outsiders, but simple facts have the power to shatter the world of a Mormon," he says. "The more you discover...the more you are pushed closer and closer to this abyss and you don't know what's at the bottom of it."

Chou researched historical inaccuracies in The Book of Mormon for three years, before sending a 16-page resignation letter to the church in 2010, and leaving officially, with his wife and their four children. (Chou and his wife later divorced, he says, because outside of their "Mormon roles," they were not very compatible. But they remain close friends.)

Mormonism is an "all or nothing" commitment, Rosen explains. "If Pandora's box is opened regarding questioning one policy or mandate, it leads to more, because it's all connected. It's not like other religions, where you can accept some parts and reject other parts. You have to accept the whole kit and caboodle. You have to accept every [church-mandated] 'calling.' You have to go to every three-hour church meeting. If I didn't go [to synagogue] for six months, the rabbi would be like, 'I am so happy to see you.' You can't do that as a Mormon."

Utah has the highest rate of clinical depression out of any state in the country, and the seventh highest suicide rate, according to a report by Thomson Healthcare. Rosen believes the LDS stance on homosexuality contributes to these statistics. One third of her patients are homosexuals who grew up LDS, and many of them were kicked out of their homes. Rosen guides these patients to the SLC PostMos and other ex-Mormon groups involved in GLBTQ activism. "These groups parallel the church in the sense that they meet every day," Rosen says. "So they can transition out of one community and into another."

Many of Rosen's patients fear losing their jobs at Mormon-owned companies, where watercooler chatter revolves around bishops, youth groups and callings. "[Ex-Mormons] have to find new peers and new families, so to speak, and sometimes, new places of employment," she says. "Leaving the church is almost like going into the witness protection program."

Preaching the Liquor Gospel

The Mormon church forbids many staples of secular life, including alcohol. In "Liquor 101," a monthly class taught by McKinnon and Chou, recent converts learn to break out of the drinking-is-evil mind-set. Because of their naiveté, former LDS have to learn everything from the bottom up, from how to pace their drinks with water and food to what brands of whiskey are acceptable as housewarming gifts.

"I was told by my dad growing up that if I ever had a drink, I'd be inviting Satan to control my spirit, and I'd be easily influenced to do horrible things," explains Karena Ball, a 39-year-old eBay seller with an eyebrow piercing.

In a brightly lit classroom inside the Utah Business Insurance Company, Chou hands out fact sheets and cues up a 20-slide PowerPoint presentation. He preaches the liquor gospel to a crowd of 47 people, some of whom he had only met online. Several of them are freshly "out" of Mormonism, and trying alcohol for the first time. "To those in the outside world, a bunch of grown-ass adults learning about whiskey would seem strange," he says, pointing to an image of an airport store called World of Whiskies. "Outside of Utah, you can buy whiskey at an airport or a mall. There are whiskey magazines. Whiskey is its own cuisine."

While Chou extols the virtues of rum, volunteers pass around antique silver trays filled with thimble-sized rum-and-cokes and piña coladas. The samples are served in official LDS sacrament cups, which Ball procured on eBay. (After leaving the church, Ball and her husband became avid collectors of ironic Mormon memorabilia.) McKinnon, donning a black T-shirt emblazoned with the phrase "PostMo and proud," demonstrates how to properly take a shot. In one swift motion, she pulls back her hair, tilts her head back, swallows and then slams the empty glass down. In unison, the group follows her lead.

It's important to teach new PostMos how to pace themselves, Chou explains. It's important to discuss how to maintain a pleasant buzz without getting sloshed. Students want to learn how to walk into a crowded bar with confidence, having memorized the terminology, and rehearsed their lines, i.e. "I'll have a Maker's, on the rocks."

One first-time attendee, a 38-year-old mother who requested anonymity, took notes while Chou spoke, jotting down terms like neat, straight up, pint and split. She had ordered her first drink at a bar two months earlier. It didn't go well. "The bartender asked if I wanted ice, and I didn't even know what to say," she says. "You leave the church, but you don't have the tools to interact with non-church people. You kind of feel like an alien."

{C}

After class, students are invited to drink the remaining liquor at an "open bar" set up on a classroom table, and a toast is raised to U.S. District Judge Robert Shelby, who had ruled the day before that Utah's ban on gay marriage violated the U.S. Constitution. (The U.S. Supreme Court, pending Utah's appeal, put Shelby's ruling on hold.) Some attendees use Liquor 101 as a safe environment to get drunk for the first time. They feel more comfortable losing their booze virginity around PostMos than around NeverMos, the term they use for the general population. Twenty minutes into the open bar, one first-timer falls to the floor, and McKinnon rushes to her side, feeding the woman pretzels and water.

Chou remembers his first encounter with alcohol with fondness and embarrassment. "There I was, a 50-year-old man, paralyzed in my car in the 7-Eleven parking lot, terrified of buying a six-pack," he says. "I didn't want anyone to see me. I paid for it in cash, because I didn't want the record on my credit card."

The SLC PostMos teach a range of classes that would mystify an outsider but are crucial to those transitioning out of LDS. They cover topics like "how to order coffee at Starbucks" and "how to shop for normal underwear" after a lifetime of wearing LDS-approved undergarments.

'You Are Not Alone'

In the hit Broadway satire The Book of Mormon, two missionaries roam a famine-stricken village in Uganda, trying to convert the natives (who are more concerned with things like war and AIDS) to their gospel. The PostMos, most of whom were once missionaries, are well-versed in the art of proselytizing, but the Internet has proven to be a more fertile recruitment tool than sending missionaries to far-flung locales.

Jeff Ricks, a 59-year-old bearded product designer, launched the website PostMormon.org in 2002, incorporating it as a tax-exempt nonprofit in 2006. Many in-real-life support groups were born on the site's message boards, which are a hub for ex-Mormons across the country. In 2007, Ricks began to raise money to put up billboards in Mormon-dominated areas, hoping to lead both doubting Mormons and ex-Mormons to his site. Thousands of former LDS donated to the cause, often generously. From 2007 to 2008, his organization raised and spent $30,000 on billboards in Provo, Utah; Idaho Falls, Idaho; Salt Lake City, and other Mormon hotbeds, and $5,000 for a full-page color ad in the Tribune.

The billboards simply state: "PostMormon.org: You are not alone." The more he put up, the more the site's traffic spiked. He says it now has an average of 10 million hits per month.

Acquiring billboard space was not easy, Ricks explains over coffee at Carlucci's. (He was on his way to the wedding of two ex-Mormon friends in Provo.) Mormon-owned companies were a no-go and non-Mormon companies in LDS territory are rare. The first company he hired, Lamar Outdoor Advertising, caved to pressure from a Mormon business that owned the land where the signpost was buried. They removed a PostMormon billboard on Highway 20 in Idaho Falls more than a week before his contract expired.

Joshua Kaggie, a 31-year-old Ph.D. student in physics at the University of Utah, became a regular poster on Ricks's site at a time when there were no weekly support groups in the Salt Lake area. Using the message boards, he organized the first meeting of the SLC PostMos in early 2011. It had four attendees, Kaggie included. Three years later, the average attendance on a Sunday at Kafeneio is roughly 40, and other branches of the group meet simultaneously in Lehi, Utah and Provo. Unlike the church, the PostMos do not have the resources to support massive public relations campaigns. They must be creative with their recruitment tactics. Using Facebook ads, they target people who have "liked" President Obama, but also list their religion as LDS or live in Utah. They see a window there - a liberal bent paired with a religion known for its conservative lean.

Many former LDS find solace online before they find their way to Kafeneio. There are 3,400 registered users at lifeaftermormonism.net, a "Social Network serving the Exmormon Community." A private Facebook group for "XLDS Singles" has 391 members, and a group for nonbelieving students at church-owned Brigham Young University has roughly 300 members. There are 11,728 members on a Reddit forum for ex-Mormons.

The church has its own way of dealing with those who question their faith. Eric Hawkins, senior manager of media relations in the LDS Public Affairs Department, said in an email that Mormons can turn to "family members, local church leaders and friends" to "talk through our questions and seek resolution." Carri Jenkins, BYU's spokeswoman, explained in an email that "ecclesiastical units" are there to provide support to students. These units are tasked with enforcing BYU's notoriously strict "honor code," which requires that students attend church, keep a "clean hairstyle" and refrain from "homosexual behavior." The same bishop that a student could turn to with questions has the power to revoke his or her "ecclesiastical endorsement," which is required for students to attend the university. Male students at BYU are also required to be clean-shaven before they are allowed to take tests for their classes.

Curtis Penfold, an atheist PostMo and GLBTQ activist, says he was kicked out of BYU in October, after he refused to repent for a feminist critique of the temple he published online, and he admitted to his bishop and stake President that he no longer believed. Within two weeks, he was evicted from BYU housing and fired from his on-campus job. He is currently living on the couch of an ex-Mormon friend.

"The church is well aware of us, combined with all the other ex-Mormon groups," McKinnon tells me, while fixing lunch with Chou at their mid-century ranch house. "We have had strange things happen at our meetups from time to time. At one coffee meetup [in Provo] someone just walked in, snapped a picture of the group, and walked out."

Ex-Mormon Karaoke Favorites

Four days before Christmas, 80 ex-Mormons gathered at Legend's Pub and Grill to celebrate Festivus, the nonreligious holiday "for the rest of us," popularized by a 1997 episode of Seinfeld. While there was no formal "airing of the grievances," there was an ugly sweater contest, which Chou won by wearing a BYU football jersey. (The prize was a fifth of Absolut.) Conversation was nearly impossible over the drunken roar of PostMos belting out ex-Mormon karaoke favorites like "Jesus Walks" and "Losing My Religion."

The libations menu included Polygamy Porter - an ale brewed in Park City by Wasatch, the same company that creates the popular Brigham's Brew root beer.

"There's no 'Spooky Mormon Hell Dream' on the karaoke list," one attendee shouts, with a dramatic pout. She wants to sing the song from The Book of Mormon musical to get the party excited about their road trip. The PostMos are planning to rent a bus to see the show when it comes to Las Vegas in June.

"I think everyone involved feels more free to be who they are," Chou says, surveying the room. "One of the most harmful things about Mormonism is that it creates false [sense of] self in people and they have to live in that space. And they think that's happiness. I did. I thought that was happiness. Once the veil lifts, you wake up and you just think, This is how life should be."