France's greatest actor, Gerard Depardieu, was so fed up that despite his Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur, one of France's highest honors, last year he moved to Russia. And Johnny Halliday, France's answer to Elvis, escaped with his Chevalier to the low taxes of neighboring Switzerland. The heirs of the classic French brands Peugeot and Chanel have also headed out the door for the same reason.

But it is not just rich celebrities who have chosen to live abroad and even ditch their citizenship rather than pay France's high taxes. They are following in the footsteps of hundreds of thousands of French people who have quietly moved abroad in search of a better life.

Their main destination is Great Britain, right next door. The United Kingdom may be France's historic enemy, but young French people with an urge to make money or start their own businesses are flocking to it.

With 70 percent of the French thinking taxes are "excessive" and 80 percent believing President François Hollande's economic policies "misguided," they are attracted by the benefits of a less regulated economy, more relaxed labor laws, a more meritocratic society, a lively business networking scene, a large pool of professional talent, and easier access to investment capital. And all this only a two-hour Eurostar train ride from London to Paris, making it easy to stay in touch with family and friends.

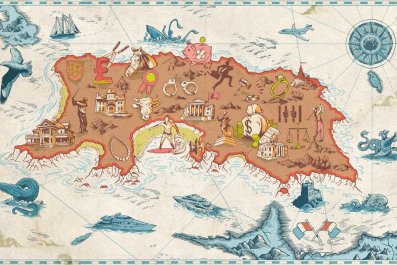

It is being billed as the biggest French invasion since William the Conqueror arrived in 1066.

Exact numbers are hard to come by. As both France and Britain are members of the European Union that allows the free movement of labor across national boundaries, French people living in London do not have to register their domicile. But the French consulate estimates that London, with a population of 7.6 million, is home to between 300,000 and 400,000 French residents, which is more than live in French cities like Bordeaux, Nantes or Strasbourg. By contrast, there are just 8,500 Brits living in Paris.

French emigrés probably represent the largest single nationality in Britain, except the Brits. And half as many again live outside London. The number of French living in Britain has risen every year since 1991 and leapt by around 10,000 in 2006.

There are certainly enough of them to keep a French-language radio station, French Radio London - call sign, La voix Française de Londres - in business with around 100,000 daily listeners. And hundreds of French companies have set up in Ashford, Kent, the first English stop on the Eurostar just an hour's ride from Paris but a world away from the restrictive labor regulations of the EU's "social chapter."

There are signs of the French invasion everywhere, and not just in their traditional stomping ground of South Kensington, near the famed Lycée Charles de Gaulle, a school funded by the French government, which has 4,000 primary and secondary pupils. Such is the pressure for a French education from prosperous parents that a new bilingual private school in Kentish Town, northwest London, the Collège Francais Bilingue de Londres, which opened in 2011, is already nudging its maximum of 700 pupils between the ages of 5 and 15. And a new French secondary school, taking 1,000 pupils up to the age of 18, is scheduled to open in the northern suburb of Wembley in 2015.

You can see it on the streets of London, too. French patisseries stacked with baguettes, ficelles, croissants and pain au chocolat are springing up. The French are everywhere. When I went into the huge Apple store on Regent Street this week I was served (very efficiently) by two young French assistants. And in my quiet North London street I have French neighbors living in both the apartment above and the one next door.

Gregory Vincent, 36, originally from near Marseilles, has been in Britain for 10 years. After five years working for a fund management company in the City of London, Britain's financial district, he branched out on his own three years ago, setting up a crowdfunding Internet business, sponsume.com, which has raised money for more than 1,300 projects.

"My perception was that France was not a great place to launch a new business, because of high taxes and red tape," he said. "The feedback I got in Britain was positive, while it wouldn't have worked so well in France.

"I did part of my studies here in England and then went on to work in the city. I guess with hindsight my opinion of France now is the same or even worse. I have met a lot of young French people with really excellent ideas, especially in the high-tech sector, but they get no encouragement in France. It's a country run by civil servants for civil servants.

"What is really outrageous is that pretty much everyone in charge [of France] come from the same background, and none of them have any experience in the private sector.

"Employment flexibility is one of the key differences between the two countries. In France what you pay the employee is doubled by taxes. In Britain the burden is much more moderate, so you can hire people quickly and easily."

Loïc Dumas, 34, runs the London end of Apéro, a business networking program, which originated in France but has spread to many other countries. In London, he organizes get-togethers and pitch sessions for young French entrepreneurs, with 620 in the meet-up group and 1,500 on his email list. He studied at Reading University and the Cass Business School in London, then became business development manager for a French start-up in London, Mailjet, a mass email business. He quit his job in December and is now looking to set up on his own.

"In France we have many more website engineers and developers" he said, "but here in Britain you have more business, management and marketing skills. It's easy to make connections here. In Paris if you're not a member of a particular circle it's difficult to make contacts. In London there are many more opportunities.

"I love London, and I'm not planning to go back to France. The people here are open, friendly and easy to approach. I feel safe. When I go back to Paris, it's a shock. When you take the Metro, it's a nightmare."

He cites easier access to venture capital as another advantage of running a business in Britain: "It's quite easy to start a business in France, but when you want to expand it's another story. There is more capital in the U.K. than in France."

Oriane Chausiaux, 31, from Paris, was working toward a Ph.D. in the molecular genetics of fertility at Cambridge when she met someone working on a business fertility project. After completing her doctorate, they launched the project together. "Seven years later, we're still in business, and I'm loving it," she said.

The firm is Cambridge Temperature Concepts (CTC), whose flagship invention is a device called DuoFertility, a small monitor worn under the armpit which transmits a woman's body temperature and sleep data wirelessly to an analyzing center to help her track the best time to try to conceive. So confident is the firm in the quality of the product, it offers customers their money back ($824) if they don't conceive within a year.

Chausiaux says, "I really love the experience of running our own business, making our own decisions and making a difference to other people's lives."

She cites three main reasons the business is thriving in England: skills, funding and the labor laws. "Cambridge is a great place, with an amazing mix of people." CTC's initial funding came from "angels," small private investors, who, as well as investing, also offer mentoring, which start-ups find invaluable.

In addition to its dozen full-time employees, CTC employs part-time consultants on flexible contracts, many of them mothers with small children. "It suits us and them very well," she says. Could they have done the same in France? "Absolutely not."

Two British academics, Louise Ryan and Jon Mulholland of Middlesex University in North London, conducted in-depth interviews with 40 French businesspeople who had moved to London and concluded that Britain's capital had become "the destination of choice" for "highly skilled people with an ambition to succeed."

The French entrepreneurs had found a noticeable contrast between "a neoliberal model of an economy characterized by meritocracy, flexibility and a willingness to recognize talent in individuals" (Britain) and a system they see as "rigid and profoundly hierarchical" (France). The French are mired in what Mulholland calls "qualificationalism" - a preoccupation with diplomas and certificates from the right institutions "which bear no relationship with the talent within the individual," resulting in "a kind of nepotistic social elite."

It wasn't only the young who were attracted to London, he said. "France is very ageist. A significant proportion of our interviewees were in their 40s. A high proportion of them said discrimination was a substantial problem. If you lose your job in your 40s [in France], you're practically dead. Here we're open to the young, but also to older people."

For Xavier Louis, 37, originally from near Nîmes, in the south of France, the big attraction of London was its pool of highly skilled talent. Eighteen months ago, along with two Belgians and an Israeli, he set up the "edu-gaming" firm Brainbow, which develops intelligence games for tablets and smartphones.

The founders have raised $1.8 million, with three investors from the U.K. and one each from France and Finland. Their latest game, Dr. Newton, was released last month and has already attracted a million users. Brainbow now employs 10, who work out of offices just off Oxford Street, London's premier shopping thoroughfare.

Like most of the other French start-up founders in London, Louis worked there in a variety of Internet jobs before he decided to fly solo, getting to meet many like-minded would-be entrepreneurs on the way. "If a city tends to attract talent, you have more chances to succeed when you create a business of your own," he said. "London is a bit like Silicon Valley in that respect. It's a bit like a football team in some ways, getting the right players in the team. In London it's easier to create the team you want.

"And while it's great to have good ideas, you need funding as well and in London you have more access to money than in Paris. Here people are more risk-taking, which gives you a better chance of success.

"London is very international, English-speaking of course, and it's very easy to grow an international business here.

"I went to work in Paris for 18 months, commuting from London. I had the possibility to relocate to Paris, but I decided to return to London to create Brainbow. If I had decided to create it in Paris, it would have been much more difficult." Now he is settled in London with his wife and three children. "There is absolutely no reason to go back," he says.

London is no paradise. Ryan and Mulholland's research found that its French residents thought the city "congested, expensive and stressful." But despite all that, said Mulholland, "One of the strongest features of the data was how happy they were here. Most had come expecting to stay only two or three years but had stayed on for much longer than expected."

Another vote of confidence comes from Chausiaux. "If I did another start-up, I would definitely do it in Britain," she said.