The country, whose economy is critical to the health of the global economy, has been living beyond its means for years. Its central bank has been flooding its financial system with easy money at the same time, and the mere whisper that that era may be drawing to a close makes financial markets tremble.

If something doesn't change, many economists say, we could be in for yet another global financial crisis, just five years after the last one.

The litany is so familiar it's easy to tune out. Economists and other financial scolds are always lecturing the United States to get its house in order.

But this isn't about the United States.

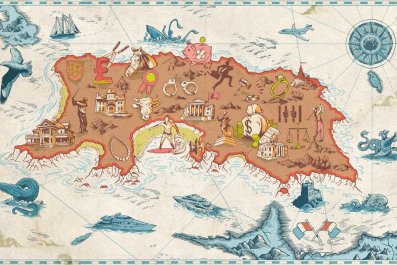

What is just beginning to dawn on a lot of people is that the same issues are in play not only in the world's largest economy, but in the second largest, too: the People's Republic of China.

Yes, the generator of east Asia's latest economic "miracle" - a country that for a decade posted nearly 10 percent annual GDP growth every year - may well stand on the cusp of its own debt crisis, something that only a relatively lonely group of so-called China bears has been shouting about for years.

They now have some high-profile company. George Soros, the legendary investor and billionaire, recently wrote a column in which he cited China as "the major [economic] uncertainty facing the world today." Beijing's growth model, Soros said, "has run out of steam." And to punctuate his pessimism, he wrote, "There are some eerie resemblances with the financial conditions that prevailed in the U.S. in the years preceding the crash of 2008."

The problem is, he's right on all counts. The arc of China's growth since its opening in 1978 has indeed been miraculous, an economic transformation rooted in reform and open trade - ushered in by Deng Xiaoping and driven by Beijing's top leaders ever since.

But in late 2008, the nature of China's economic growth changed. When the U.S. crashed and the developed world quickly fell into recession, China's leaders panicked. Desperately fearful of unemployment and the potential unrest that could cause - particularly in the more prosperous, export-dependent parts of the country in the southeast - Beijing began throwing money at its economy at an epic rate.

A nation that was already building out infrastructure massively - high-speed railways, subway systems, bridges - doubled down. Total economy-wide debt increased from 125 percent of GDP in 2008 to 218 percent at the end of last year, according to an estimate from Fitch Ratings.

Credit expanded $15 trillion - from $9 trillion to $24 trillion - in just five years. As Patrick Chovanec, managing director of investment firm Silvercrest

Asset Management and a former professor at Beijing's Tsinghua University, points out, that $15 trillion is the size of the entire U.S. commercial banking sector.

The credit binge had its desired effect. China not only avoided the global slump, it continued to grow rapidly. Unlike in the United States, where President Barack Obama once lamented, "a lot of those shovel-ready jobs [he'd wanted to create via government spending] weren't as shovel-ready as we thought," infrastructure jobs in China were shovel-ready, there being no regulations or pesky environmental studies to get in the way.

Crisis averted - or so it seemed - and more than a few Chinese officials and businessmen came to believe the hype about the "Chinese miracle," crowing about how Beijing had created a new growth model, superior to anything in the West. The echoes of Japan in its "bubble economy" era of the late 1980s were unmistakable.

Now, the growing worry - articulated by Soros and others - is that the Japan analogy may be all too appropriate. Japan's debt-driven bubble burst in the early 1990s, and the country has barely registered an economic pulse since. (Newsweek, it should be noted, was the first to ascribe the term The Lost Decade to the 1990s in Japan.) Is China headed down the same path?

Chovanec, among others, points to some unsettling signs that the answer may be yes. He argues that two episodes (one last June and one just two weeks ago) of sudden unexpected interest rate increases in China's interbank lending market signal that the "foundations" of China's investment-driven growth model "are crumbling."

They reflected, he and others argue, the panic that ensues in China's financial markets when the central bank - the People's Bank of China - tries to tighten liquidity, even slightly. So addicted are China's banks to an ever-expanding supply of credit - necessary in part to roll over unacknowledged nonperforming loans (shades again of Japan and its "zombie" borrowers in the 1990s) - that they panic and seek short-term funding in the interbank market, driving rates way up.

In both cases, the People's Bank of China had to step in and inject huge sums back into the market to calm everyone's nerves and get rates back down. "China's leaders," says Chovanec, "are riding a runaway train that they don't quite know how to stop."

Less pessimistic analysts note that the overall amount of debt relative to GDP is not at unserviceable levels - at least not yet.

Charlene Chu, Beijing-based analyst for Fitch, notes that China possesses attributes that "arguably make such high leverage more wieldy than elsewhere." The authorities have greater control over borrowers and lenders than in most other countries, have a solid policy record, as well as a (mostly) domestically funded financial sector and a closed capital account, meaning that China is not vulnerable to having "hot money" bolt the exits at the first sign of trouble, which is what triggered the "Asia Crisis" of the late 1990s in countries such as Indonesia, Thailand and South Korea.

All of that is true, but in the mind of many economists, if China doesn't move to rein in credit, the economic facts are undeniable. Even if China manages to evade the 2008-style crisis that Soros recently invoked, at minimum, says Chu, "swelling debt burdens will constrain economic activity as greater resources are directed into debt servicing."

China's miracle days, in other words, are drawing to a close.