"This is a country area, so after a hard day it's nice to drive in to Stettin and go to a café," said Detlef Horn, reflecting on how some rural Germans now choose to spend their evenings by going to Poland to relax.

Horn and his fellow inhabitants of German towns with Polish names like Löcknitz, Penkun and Zerrenthin are quietly changing world history. They live close to Germany's border with Poland and cross over as part of their daily lives: to go shopping, to go to the movies, to eat out, to visit the doctor or dentist.

This isn't just any national boundary. The German-Polish border is one of history's most contested and fought-over. Adolf Hitler set off World War II in 1939 when he invaded Poland with the goal of creating Lebensraum, more space, for Germans to live in.

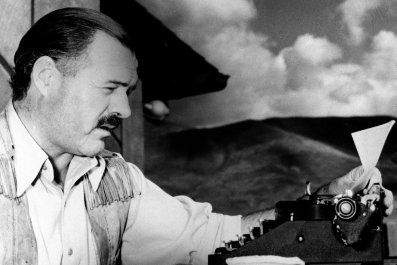

Eighty years earlier, Otto von Bismarck, the Prussian chancellor who unified a number of small states into what we now call Germany, wrote to his sister: "I have every sympathy for the Poles, but if we want to continue to exist, we can't do anything else than eliminating them."

Making matters worse, Poland's bullying neighbor Russia has a long history of cannibalizing Poland from the east. With both Germany (Prussia) and Russia having treated Poland as an easy pawn to be taken for so long, Poles could be forgiven for feeling acute unease over the geographical location of their beloved country.

And now Germans are once again enjoying the pleasures of Stettin, the bustling city renamed by the Poles as Szczecin, which Germany lost to Poland in the settlement after World War II. But this time the German invasion is different.

There are no alarm bells going off in Szczecin today. On the contrary, the city is warmly embracing its German visitors, which is helping this northern trading post regain some of its old prominence.

"Today Germany is not our enemy or competition," Lech Walesa, the Polish dissident, trade union leader and Nobel Peace Prize laureate who was perhaps more than any individual responsible for the collapse of the Soviet Union and the liberation of Poland from communism, told Newsweek. "Instead, today we belong to the same common European family."

And many Poles are automatically looking west, to the German capital, rather than their own, Warsaw. "Here in Szczecin, a lot of people regularly go to Berlin," said Dariusz Chojecki, a professor of history at the University of Szczecin. "Some of them have never been to Warsaw."

Ordinary Polish citizens are joining their German counterparts in their history-altering border habits by packing up and moving west across the fateful Oder-Neisse line - the two-river line drawn by the Yalta Conference that gave vast tracts of German territory inhabited by Germans to Poland - as they are entitled to do under the European Union's rules guaranteeing the free movement of labor.

This radical population shift suggests a time when national historic borders become anachronistic and wither away.

"Obviously, this [Polish-German] border actually exists and will exist," said Walesa. "We have, however, to bear in mind that in the era of ever-growing technological development, we can no longer be confined to administrative state borders.

"Hence the necessary enlargement of the structures of economic, defense and other cooperation is a must in today's world. Under such circumstances, the lifting of barriers and divisions is certainly a positive process that can benefit us all."

"Today is completely different from 10 years ago," said Horn, a real estate agent, who is married to a Polish woman. "Two years ago [after Poland joined the Schengen area], the number of Polish buyers really started increasing. Very wealthy Poles still build themselves a nice house in Poland, but we're getting the affluent bourgeoisie. It's really a cost issue. You can buy houses cheaper in Germany."

In 2013, Horn sold 55 homes, 15 of them to Polish families. With properties ranging from around $48,000 to $206,000, and with the local, state and German federal government providing first-class services, moving to Germany is an attractive, affordable proposition.

"I bought a house here for the same amount that a two-room apartment in Szczecin would cost me," said Anita Olejnik, a political scientist now living in the town of Penkun who commutes across the border to her university job in Szczecin. The state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, formerly part of communist the German Democratic Republic, located along the northern part of the German-Polish border, is making the move even more attractive to Poles by simplifying the paperwork.

That's because it needs more residents. Lebensraum in reverse, you might call it. In the first decade after Germany's reunification in 1990, a quarter of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern's residents left the state, mostly for the more prosperous western part of Germany - the old capitalist, genuinely democratic West Germany.

"The Germans were worrying what to do, because doctors and other professionals were moving away," explained Agnieszka Lada, head of the European Program at the Institute of Public Affairs in Warsaw, who is conducting a research project on the new cross-border movements.

"On the Polish side there are jobs, but it's not a very nice area to live, so Poles are deciding to move. Germany is a green and pleasant place. People are environmentally conscious. There's a good life to be had here. But it's not something poor people can do. Germany is still expensive if you're unemployed or have a low-paid job."

Indeed, the new German-resident Poles often keep their jobs in Poland, commuting across the border. "Of course some Poles move here to take advantage of Germany's welfare system, but most of us want to make a difference in the community," said Olejnik. "Here in Penkun there are now lots of academics like me and others are have started small businesses."

An example of a Polish firm that has filled the gaps left by west-migrating Germans is Fleischmannschaft, an operator of a plant in Löcknitz that prepares spices for meat wholesalers.

Then there is Train Electric, a Polish-owned manufacturer of train parts, that employs 10 Germans and Poles in Löcknitz. It is putting down deep roots in the community and sponsors the local soccer team.

Germans, for their part, cross the border to take advantage of Poland's noticeably lower prices and the wider selection of stores and entertainment to be found in Szczecin, a city almost eight times larger and far closer to them than the nearest big German city.

The German-Polish border is, in fact, fast disappearing, not as the result of political decisions but thanks to ordinary citizens voting with their feet and the operation of the free market in goods and labor provided by the European Union. Löcknitz, which lost a fifth of its 3,500 residents between 1993 and 2004, has reversed its population decline. Today 300 of the 3,000 residents in this town 16 miles from Szczecin are Poles.

Across Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, it's much the same picture. This austere region, which lacks major industries except for shipping (it's on the Baltic) and renewable energy, still has one of Germany's lowest proportions of immigrants, 2.5 percent. That figure is, however, a 0.2 percentage point increase over 2003.

In 2012, 10,000 foreigners moved here, a 20 percent increase over 2011, and Poles made up the largest group. In some areas, 76 percent of the foreign-born residents are now Poles.

"Our Polish residents enrich our community," noted Ulrike Bohl, a pastor in the town of Zerrenthin. "And thanks to them, we don't have as many empty properties. There have even been a few weddings between German and Poles, which is a really nice thing."

Today Germany is the second-most popular destination for emigrating Poles - after the U.K. According to Poland's statistical agency, at the end of 2010, 455,000 Poles lived in Germany, compared with 560,000 in the U.K.

If all of this seems inevitable, think again. Just 24 years ago, this very border, which locals now virtually disregard, was the touchiest issue in the two Germanies' reunification negotiations with their World War II victors - the United States, Great Britain and the Soviet Union.

Would Germany become a peaceful behemoth at the center of Europe, more interested in living happily ever after than in military expansion? Or would it forcibly try to regain its lost areas east of the Oder-Neisse line?

The American, Soviet, British and French diplomats responding to the two Germanies' reunification plea in the so-called 2+4 talks - the two Germanys and the four allies, but without Poland - had no way of knowing.

"Both the West [Germans] and the East Germans were more willing to concede things to the Soviet Union than we were, but the border was the one issue where the Germans didn't want to make concessions," recalled Michael Young, then a Deputy Undersecretary of State, who served on the American negotiating team. "They wanted to return to the pre-World War II borders."

West Germany had, in fact, never officially accepted the Oder-Neisse border, the line along the two rivers which awarded Poland large chunks of German territory inhabited for centuries by native Germans at the end of hostilities in 1945. In 1970, however, West Germany acknowledged it as the de facto border. (East Germany's position was, of course, dictated by the leaders of the Soviet Union.)

No surprise, then, that the 2+4 talks caused huge anxiety on the Polish side. Young explained that for this very reason the Polish government argued it should take part in the negotiations to make its own case.

The Americans, placing their bet on a peaceful Germany, supported unification. "I thought the Germans had come to grips with their history and didn't pose a danger to the world," recalled Philip Zelikow, another key member of the U.S. negotiating team. But the other allies were passionately opposed to the idea.

At one point during the negotiations, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher exclaimed, "We defeated the Germans twice! And now they're back!"

French President François Mitterrand, too, tried to prevent West Germany's eastward expansion by invoking specters of the past. "The Soviet Union [Poland's Warsaw Pact partner] didn't end up playing a big role on the Polish border issue, but France did," explained Zelikow. "[France] saw itself as an ally of Poland. Mitterrand himself was fond of speaking in national stereotypes, for example warning against 'the return of Prussia,' and referring to Munich and 1914. Those are pretty apocalyptic analogies."

Zelikow, a member of the National Security Council in George H. W. Bush's White House and now a professor of history at the University of Virginia, went on to write a paper on Germany's unification, Germany Unified and Europe Transformed: A Study in Statecraft, together with his security council colleague Condoleezza Rice.

In the end, the gradual collapse of East Germany's state apparatus even as the diplomats were negotiating the future of the two Germanys made reunification virtually inevitable, and the two parts became one on October 3, 1990, with full acceptance of the Oder-Neisse line as the single Germany's eastern border.

Even before the unification treaty was signed, residents of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern started leaving their poor eastern backwater for a better life in the west. According to Eurostat, the European Union's statistical agency, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern still has Germany's lowest gross domestic product per capita, and, according to the latest German unemployment figures, it has the country's worst jobless rate, with 11.3 percent unemployed.

History is repeating itself but with a twist. In the late 1900s, Chojecki, who studied migration across the German-Polish border, found that Germans had always left this poor region for better chances farther west. Deprived of local labor, Prussian landowners responded by importing Polish workers.

Now Mecklenburg-Vorpommern needs Poles again, preferably ones who'll hire unemployed local Germans. "This is a demographically damaged region, and Poland is our big opportunity," explained Lothar Meistring, the mayor of Löcknitz. "Thanks to the Poles, our population is growing, because it's not elderly people moving here, it's families. Now we're having to expand our schools because there are so many children."

In several German towns, between 20 and 30 percent of schoolchildren are now Polish. As one German newspaper put it: "Help! The Poles are rescuing us!"

"For the past 24 years, the border hasn't been a cause of diplomatic antagonism," said Walesa, who became the country's first democratically elected president after the end of the Cold War. "I never suspected there would be any attempts by the German government to move the Oder-Neisse border. Never in history have we enjoyed such good diplomatic and economic relations."

Farther south along the border, Frankfurt an der Oder's city buses now go to Slubice, the city's twin on the Polish side. So does public transportation in Görlitz, Germany's easternmost city. Both cities were divided by the Oder-Neisse line.

"The border region has become an in-between area, not fully German and not fully Polish," said Gabriela Christmann, a researcher specializing in the German-Polish border at the Leibniz Institute for Regional Development and Structural Planning.

"The physical border has disappeared, though it will take longer for people's mental borders to fall. The development is going toward people in this area creating a joint new identity. The Polish-German history is a very difficult one, which is why this is such an important development."

"The border region is changing very quickly, and the cross-border life is slowly becoming normality, though of course it will take longer than a similar development at, say, the German-French border," added Olejnik. In a further sign of cross-border collaboration, a German-Polish group called Pomerania gets its funding from Warsaw, Berlin and Brussels.

Not even the Americans, the most optimistic about Germany's reunification, predicted this German-Polish rapprochement. "Did we foresee it? Absolutely not," conceded Young, now president of the University of Washington. "Germans and Poles have moved across the border for centuries, but forcefully. The countries have a long history of colonizing this area, which made the issue of where the border should be so difficult."

No doubt her home state's experience with its Polish neighbors informs the policies of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern's most illustrious MP, Angela Merkel, whose hometown of Templin has lost about 3,000 of its 19,000 residents since German reunification.

But not everything is peaceful along the quietly vanishing border. Perhaps unsurprisingly, suspicion and prejudice remain on both sides. In the 2011 state elections, the far-right National Democratic Party won 6 percent of the votes in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, their best result in the country, largely by focusing on Polish immigration. The party now has five seats in the state parliament.

"The far-right people are ruining the atmosphere," said Bohl. "And they do have a lot of supporters. Some Poles don't maintain their houses, and that's giving the far-right ammunition."

An outbreak of theft further clouds the picture. "Every day something gets stolen," lamented Bohl. "Of course we can't be sure who's behind it, but as far as we know, sometimes it's Polish gangs, sometimes Lithuanians, sometimes Ukrainians. That makes the situation worse for the Poles living here."

According to the police, between 2007 and 2009, car thefts dropped by 21.4 percent, but between 2009 and 2011 they rose again, by 8.6 percent. And the thieves don't stop at cars. They take agricultural machinery, even statues. Some Germans are suggesting police helicopters should patrol the border.

But even in theft-plagued towns, the majority see the open border as their best future. "Looking west is silly for us here," said Bohl. The west is very far away. We have to look east!"

Meistring revealed that even far-right German voters in Löcknitz visit the town's Polish doctor. For Poles, the choice is simple. "The bottom line for Poland is this: Is it better to be a subordinate partner of poor, corrupt Russia, or a more or less normal partner of rich, generous Germany?" explained Charles Crawford, a former British ambassador to Warsaw. "It's not a tricky decision."

Germany or Russia: That's what Poland's choice boils down to; and, for perhaps the first time ever, it's a real choice. Today, noted Zelikow, "Polish anxieties and animosities run deeper toward Russia than toward Germany. Both the Germans and the Russians have done terrible things to Poland, but Germany has expressed regret, whereas Russia has not.

"Looking at today's situation, I don't think Angela Merkel imagines that she's Otto von Bismarck, but I think Vladimir Putin imagines that he's a bit like Czar Alexander III [who was also king of Poland]. Today the Russians are looking toward the past; the Germans are not. "

Walesa envisions a future that goes much farther than Germans shopping in Szczecin and Poles moving to Zerrenthin. "We have to realize that we're a special generation," he explained. "Having overcome the deepest divisions and the greatest dangers, we've started constructing European integration. We're eliminating borders among countries, and in many issues we've been establishing a single state called Europe.

"I'm not at all surprised by [the integration process at the German-Polish border], since it's an element of a growing continentalization, with globalization to follow in the longer run. We're free to move around, we can freely choose from among the most convenient variants for us. This is merely a symptom of the era in which we happen to be living."

While German and Polish leaders are slowly waking up to such ideas, locals on both sides of the border are one step ahead. As Olejnik observed, "I have the feeling that politicians in Berlin and Warsaw don't realize how far we've come here. They say things like, 'Wouldn't it be nice to do things together?' But we're already doing it!"