The dead don't talk, but they have been known to file taxes.

Scamsters who gain access to the social security numbers of deceased Americans have fooled the Internal Revenue Service again and again. When Congress passed its budget bill last week, it attempted to end that fraud by walling off the nation's "Death Master File." But the premise, say forensic researchers and genealogists, is dead wrong.

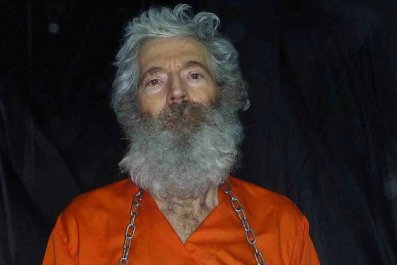

The Death Master File, known to all who use it as the DMF, pools the death records of nearly everyone in the U.S. - who had a social security number - since 1936. A large swath of the information is offered via the file's public interface, the Social Security Death Index, and is used for everything from locating families of lost service personnel to finding the next of kin of those who are dying and unable to speak.

The data in the file also help forensic analysts work with geneticists to establish patterns of illness in order to qualify families for genetic testing, then track down family members at risk from killer diseases.

The drawback is that fraudsters around the world also use the DMF - which includes the social security numbers of dead people, who are not included in protective privacy laws - to hoodwink the Internal Revenue Service into sending them billions of dollars in tax refunds.

The budget bill includes a restriction on general access to the DMF to put a stop to this fraud and help save the Treasury $60 billion over the next fiscal year. The fact is, far from stamping out fraud, the restriction is likely to cost the nation just as much, if not more.

"Closing the Death Master File is ludicrous," said Melinde Lutz Byrne, one of the nation's top genealogists and part of a small group of forensic researchers at Boston University. They have banded together and for two years have fought similar proposals in Texas and Florida to block public access to the Death Master File.

"It is my opinion that the science of it all has bypassed our elected representatives and even the courts," she said.

The real problem, she and other experts say, is not the DMF, which millions of Americans rely on to track their ancestors, reunite families, locate heirs and guard against disease. It's the IRS and its inability to prevent fraud.

"The IRS is handing out money like candy - and nobody wants to acknowledge it," said Sharon Sergeant, a forensic researcher, technologist and tax-software programmer who strongly supports the Boston University group. "Why isn't it checking to make sure dead people aren't getting tax returns? Somebody who reads the obituaries and makes up a social security number the right way, according to the algorithm, can file a tax return and get a payment. It's got nothing to do with the Death Master File. It has everything to do with the IRS not doing its job."

In fact, because the DMF has long been used by financial institutions as well as the IRS, to ascertain whether someone is dead or alive, putting the DMF behind closed doors will only increase fraud, Lutz Byrne says. "It's not going to stop fraud, because it's not the source of the fraud. It's killing the messenger. The DMF is what allows you to stop the fraud. I wonder if the IRS is now sending out more money than it's taking in."

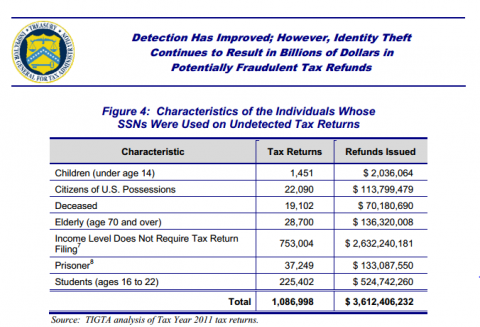

According to a September report from the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, the IRS doled out more than $3.6 billion of what appears to be fraudulently filed tax returns in 2011, the latest tax year for which it has data. Of that total, only a fraction came from dead individuals - about $70 million. And there's no evidence those individuals' data was mined from the DMF.

Much of the problem of inappropriate refunds could be helped by the IRS simply checking to see if a person is dead before sending them a return. After all, it has unrestricted access to the DMF.

"Identity theft continues to be a serious and growing problem, which has a significant impact on tax administration," the Treasury said in its audit. "Undetected tax refund fraud results in significant unintended federal outlays and erodes taxpayer confidence in the federal tax system."

All of this has fallen on deaf ears in Congress. Legislators have taken up the idea of restricting access to the DMF, inspired by stories of those who have filed tax returns, only to find someone else had beaten them to it - or, in the saddest cases, claimed a dead child as a dependent only to find someone else did it before them.

"For far too long, identity thieves have been exploiting the Death Master File to steal Americans' identities to obtain fraudulent tax refunds," said one of its progenitors, Representative Sam Johnson, R-Texas, who is chairman of the Ways and Means Social Security Subcommittee. "Taxpayers who are victims of such fraud endure the terrible ordeal of proving their real identities. That's just plain wrong."

The Senate measure this week seeks to restrict access to the DMF - which has been accessible to the public electronically since the 1960s - for three years, notwithstanding the demands of the Freedom of Information Act. Access by third parties will only be allowed for those who can show a legitimate fraud-protection or business interest and also demonstrate they have the ability to protect all information procured.

This will be determined through a fee-based certification system to be established by the Department of Commerce. Financial penalties will be meted out to those who improperly disclose the data. In addition, criminal penalties of up five years in prison or a fine of up to $250,000 will be imposed on anyone found to be filing fraudulent tax data.

How much money this will save or generate is shaky. Senate aides have deferred to a section-by-section analysis of the budget deal conducted by the Cato Institute, a libertarian Washington-based think tank, that estimates the legislation to wall up the DMF will result in reducing the deficit by $786 million in 10 years.

As part of that total, it calculates fees from the new program to be set up by the Commerce Department to certify those who may be allowed to access the DMF will generate $517 million during the same decade.

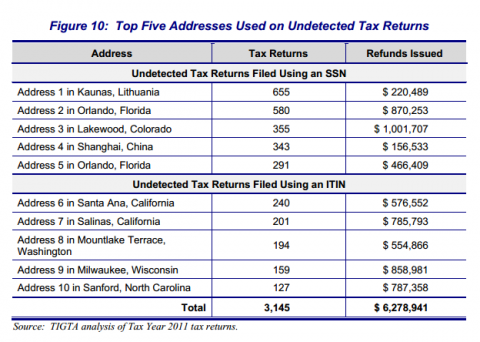

And yet, the change is unlikely to address the real problem, proponents of the DMF say. A close look at the Treasury audits of the IRS shows just how egregiously poor the agency's controls are. For instance, the top five addresses used on fraudulent tax returns in 2011, combined with the volume of payments to those addresses, should have raised all kinds of red flags at the IRS - but didn't. They include Kaunas, Lithuania, which received 655 returns at the same location, and Shanghai, which received 343 at the same location.

Three of the top five addresses were in the U.S., in Lakewood, Colo., which received more than $1 million of IRS payments across 355 payments in 2011 alone, and Orlando, Fla., where fraud appears to be at its most prevalent, with two addresses fetching the balance: 871 separate tax returns totaling more than $1.3 million.

While the IRS plans to improve its filters and processes to authenticate taxpayers on an enterprise-wide basis, the Treasury noted in its recent report that it has yet to prevail on the agency to agree to "limit the number of tax refunds issued via direct debit to the same bank account." It estimated the IRS's revamped processes will not be in place until 2017, resulting in a loss of up to $385 million a year.

Until then, the IRS will be heavily reliant on its 201 partner financial institutions to help it identify and return questionable tax refunds, Treasury said.

In 2012, the IRS recovered 210,003 fraudulent tax refunds totaling more than $779 million through those partnerships. Compare that with an estimate from the White House budget office of nearly $108 billion of improper federal agency payments for the same year, according to the Government Accountability Office.

"Right now, the question is, what does it take to get the IRS to pay you cash money? The answer is, all it takes is a social security number and name - and the IRS won't check it!" says Barbara Mathews, one of the genealogical instructors at Boston University who champion leaving the DMF alone and tackling the real issue - the incompetence of the IRS.