It was four days before Christmas, 1988, and the day started out like any other. Victoria Cummock, a 35-year-old interior designer in Coral Gables, Fla., dropped her three young children at preschool, picked up her mother from the airport, then headed to work.

She had a thriving business and was in the midst of remodeling a house. The workmen were on site when she arrived, wielding sledgehammers and listening to the radio.

"Suddenly, the announcer said a plane had gone off the radar and crashed into a town in Scotland called Lockerbie. I said, 'Oh, Mom, that is right near the town where John is from,' " Cummock recalled, referring to her husband, a 38-year-old marketing vice president with the Miami-based Bacardi Foods Group, who was in London on business.

She had just spoken with him that morning and knew he was set to fly home the very next day. Cummock asked the workmen to turn off the radio to observe a moment of silence. "So here are these big, burly construction workers looking at me like, What?

"I said to them, 'It's four days before Christmas and a whole plane load with hundreds of people just fell out of the sky. Obviously they're all dead. Can you imagine what their families are going to go through and how this will affect them the rest of their lives? We have to pray for all of the people on the plane and their families, because things will never, ever be the same."

And so the workmen bowed their heads, sledgehammers dangling in their hands, as Cummock, a tall, elegant brunette, led them in a short prayer. Then they turned the radio back on and went back to work. It wasn't until much later that night - after making dinner, putting her children to bed and wrapping presents with her mother - that she learned her husband was on that flight.

She was right. Things were never, ever the same again.

Twenty-five years ago Saturday, Pan Am Flight 103 took off from London's Heathrow airport en route to New York City. Thirty-eight minutes later, at 31,000 feet in the air, a bomb onboard the Boeing 747 exploded, sending wreckage, bodies and debris flailing down over Lockerbie, Scotland, killing all 259 people on board and 11 more on the ground. The youngest was just two months, the oldest 82 years. Many were in their 20s. It was the deadliest act of terrorism against American civilians until the morning of September 11, 2001.

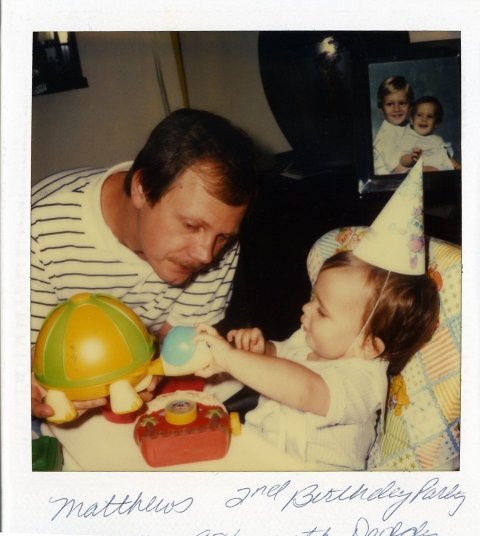

John Cummock, who had decided to catch a flight home a day early to make it back in time for his daughter's third birthday and his family's pre-Christmas preparations, was one of 189 Americans killed. He sat in seat 3A.

"I'm often asked by people, 'When do you think you'll be able to put all of this behind you?' " said Cummock, whose children were three, four and six years old when their father died. "In the case where there is mass murder and terrorism and a lack of accountability and justice, that until we get closer to the truth, it's very hard to set this behind us."

Cummock met her husband at the manufacturing company Chesebrough Ponds, in Greenwich, Conn., where she worked in the finance department and he was a marketing director. She overheard him talking with a salesmen in Spanish.

"He was one of the few WASPy, preppy guys in Greenwich who was multilingual and well-traveled," she said, "and I'm half-American and half-Peruvian. He struck up a conversation with me, and I answered him in Spanish."

Cummock's voice sounds unfathomably grounded and smooth as she describes that fated night - how her husband's boss came over, shaking and white as a ghost, to tell her that John had been on the plane. "'You don't know? Nobody's told you?' he asked her. I said 'No, no, no, I spoke to him this morning. He gave no indication that he was going to change flights.'"

She called John's London office, then the local minister, and then she started dialing Pan Am's emergency number. "Initially when I got through to Pan Am, they were asking me questions. Who are you? What's your husband's name? How old is your husband and how old are you?

"They're asking me all these questions and I'm just trying to ascertain whether he was on the flight. But Pan Am had already released the manifest to the media, so while I couldn't get confirmation, media was starting to gather outside the house."

Only after she threatened to walk outside and tell the press how unhelpful Pan Am was being did the airline finally confirm that John had indeed perished on flight 103. It was the middle of the night, and Cummock used the handful of hours she had before her children woke up trying to find a psychiatrist to help her understand how to tell them the news.

"I didn't want to traumatize them even more with all of this, but I also didn't want to lie to them. By then, there were dozens of people outside my house and I didn't want them to be frightened or cause them any more pain."

As messy and horrific as the crash was, the aftermath only got worse.

Some families were delivered the wrong bodies, Cummock said, but didn't find out until after they had buried or cremated them. Others didn't know how to get their family members' bodies at all. In the first few months after the bombing, Cummock says she didn't receive an acknowledgement from the U.S. government about what had happened. No one reached out to her until the event was defined as an act of terrorism.

"I always said, if John had been killed in Miami I would have had the courtesy of a police officer saying he was murdered, the body is here, we need to hang onto it for a certain amount of time, or something like that. We also would have been updated or given a contact person.

"But since terrorism happens to somebody else somewhere else, there were no protocols and no one in charge. We couldn't get death certificates for over a year because no one was coordinating that."

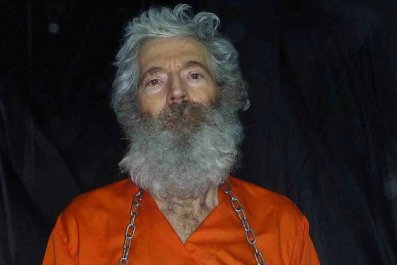

In 1991, U.S. and British investigators indicted Libyans Abdel Basset Ali al-Megrahi and Lamin Khalifa Fhimah for the Pan Am bombing. It wasn't until 1999 that Libya handed over the suspects and agreed to a trial in the Netherlands under Scottish law, where the death penalty is not permitted.

Only Megrahi was found guilty. He received a compassionate release from prison in 2009 when he was diagnosed with terminal prostate cancer. President Obama called the decision "a mistake," saying, "We have been in contact with the Scottish government indicating that we objected to this." Doctors said he was near death, yet he lived until May 2012.

Evidence also suggested the involvement of higher-level aides to Qaddafi, but no other charges have ever been brought. In 2003, Qaddafi offered $2.7 billion in damages to families of those killed in the bombings. Al Megrahi remains the only person convicted.

Sixteen days before the bombing, a man with an Arabic accent (later identified as Yassan Garadet) called the U.S. embassy in Helsinki, Finland, warning of a planned terrorist attack on an unknown Pan Am flight. While the call, known as the Helsinki Warning, was circulated among embassy and airline officials, it was not considered credible.

Security at Frankfurt airport, where Flight 103 originated, discovered the message a day after the bombing, hidden under a stack of paperwork.

Cummock says she has learned of 11 bomb warnings for Flight 103, "but there were no mandatory procedures. Pan Am hand-searched and x-rayed unaccompanied bags. They advertised that they had the best security in the system and charged passengers a surcharge."

Yet she alleges that the company prioritized timely departures over security. The more she found out about what brought down the plane and the lack of airline security, the more she wanted to help professionalize airport security.

"Unfortunately, up until 9/11, security people were basically minimum wage employees hired by airlines who had minimal training," she said. "None had criminal background checks."

Cummock has spent the past 25 years chasing justice.

"Those who perpetrated the act have not been brought to justice," she said. "It has been a case of political expediency for commerce. The two Libyans who were indicted were only the bag men in the situation. They were the ones who got the bag on the plane. Those who funded the operation and the bomb maker, they had originally been pinpointed by the FBI and CIA, but with the trial at the Hague against Libya, the U.S. washed their hands of it."

She is especially disturbed that the trial wasn't held in the U.S.

"Nobody bombed Lockerbie," she said. "They bombed a U.S. air carrier flying an American flag almost entirely filled with Americans. But the oil companies didn't want [an American trial] to occur because they wouldn't get the oil concessions they wanted. U.S. oil companies pressured the State Department and Department of Justice not to try the case against the two Libyans, so they allowed the U.K. to try the Libyans, which to me was such a betrayal of my husband."

Over the past 25 years, Cummock has transformed herself from an interior decorator to a leading advocate for air disaster and terror victims. She has testified before 28 congressional committees, worked with three presidents and helped Congress ratify two international treaties and nine pieces of federal legislation, including the 1990 Aviation Security Improvement Act, the 1996 Foreign Sovereign Immunity Waiver and the 1996 Iranian-Libyan Sanctions Act.

President Bill Clinton appointed her White House Commissioner of Aviation Safety and Security and she also served as a board member of the Federal Aviation Administration Security Advisory Committee.

She was the only Pan Am Flight 103 family member to meet with Qaddafi to help negotiate restitution - as well as the only family member who did not accept the "no-fault settlement" and who successfully tried her case in federal court. Cummock also met with Libya's former minister of justice Mustafa Abdul Jalil, who led the rebels to overthrow Qaddafi's regime and became the first prime minister of Libya in more than 40 years, and who in 2011 claimed he had evidence that Qaddafi personally ordered the bombing.

"I asked Jalil if he's given his evidence and testimony to the authorities and he said no one has come to him about that. He said, 'We've been talking about oil and our policies and support for our revolt, but nobody has talked to us about terrorism and Pan Am 103.' "

Once again she went back to the American authorities, asking how many people were working on the case and whether or not they had talked with Jalil. "How can my lawyers and I access Jalil and you're saying it's too violent and volatile a case to go to work on?" she asked. "This case is beyond me. We want a real investigation.... If there is no accountability, history will repeat itself."

The lesson she draws from such stonewalling is plain. And the horrendous consequences of such obfuscation a dozen years later are horribly obvious.

"We all feel that this has been a great miscarriage of justice for oil and for commerce," she said. "A quarter of a century has gone on and people have forgotten that this was the first attack against Americans. There's a whole generation of people 40 or under who think it was 9/11. But the writing had been on the wall."

Every year since the day that changed everything, Cummock has gathered with her children on December 21 to remember and honor her husband. They light candles. They share memories. They hold a family service. If they are at home in Miami, they visit the memorial garden at their local church. This year they will be in New York City, where they'll spend the day outside, enjoying nature, just as John always did.

"Obviously, with the kids being so young, their memories have faded, but I always talk to them about what special things their father did with them or loved about them," she said. Like how John was a football fanatic who dressed up his kids in Miami Dolphins jerseys, plopped them down on the couch in their baby seats and watched games with them. "I was a football widow," she laughed, "but he had his own football fan club."

John took his children on bike rides and lunch dates. He held tea parties with his daughter and let her dress him up in hats and boas. He taught all three to swim and play water polo. Born in Utah, raised in California and half-Scottish, John was a gentleman in every sense of the word.

"He was very committed to his young family and mindful of how lucky he was," Cummock said. "He had a great sense of duty to serve those less fortunate and did a lot of community service. And he really adored his kids."

When her children were younger, they would dress up and go to the church's memorial garden in Florida. "My daughter would say, 'Daddy, this is my new Christmas dress. I hope you like it.' Oh my god, break my heart," Cummock said, pausing.

"At this time we always mark where our life is, whether the kids are in medical school or graduated from college, or just won the pennant for water polo or whatever... It's been quite a journey watching them through the years."

John Cummock is buried in Tundergarth churchyard on a grassy hill overlooking Lockerbie, an hour away from the town of Cumnock, which was named after his ancestors. Across the road is the field where the nose of Pan Am Flight 103 plummeted violently into the ground.

Everything here is beautiful: the majestic mountains, the farms, the pastures and the many animals who make their home there. John's gravestone, which is made from the same stone as the base of the Statue of Liberty as well as the Pan Am 103 Memorial in Arlington Cemetery, is inscribed with his favorite poem, "Success," by Ralph Waldo Emerson.

To laugh often and much;

to win the respect of intelligent people and the affection of children;

to earn the appreciation of honest critics and endure the betrayal of false friends;

to appreciate beauty;

to find the best in others;

to leave the world a bit better....

whether by a healthy child, of garden patch or a redeemed social condition;

to know even one life has breathed easier because you have lived. This is to have succeeded!

"I don't think you ever get over something like this," Cummock reflected. "You learn how to live with it. Over the last 25 years I've had a wonderful life, and I feel very centered about all the good that has come out of such a terrible act. For an interior designer from Coral Gables to affect international and national policy and now know that as different tragedies move forward, people will be treated differently," she said, trailing off.

"Whether it was Oklahoma City or 9/11, we know that families are being handled with dignity and with respect, not by an airline employee but by our government."

Cummock paid a high price to ensure that others are treated better than she has been. It is small comfort, but out of sudden, heart-breaking tragedy has at least come good.