Last Thursday, an urgent call went out from CIA headquarters to the spy agency's director, John Brennan, who was giving a speech to a graduating class at The Farm, the CIA's training facility near Williamsburg, Va. Brennan was warned that the Associated Press and The Washington Post were about to publish the results of a long investigation revealing that Robert Levinson, a retired FBI agent who had gone missing while "on private business" in Iran six years ago, had actually been working for the CIA.

A handful of national security reporters in D.C. had known of Levinson's CIA connection for years but agreed to sit on it, accepting the CIA's rationale that publishing the information could endanger the life of Levinson, who was ostensibly pursuing an investigation of cigarette smuggling for a private client when he went missing on Iran's Kish Island in March 2007. Levinson was thought to be in Iranian hands.

On Thursday morning, the entreaties of lower ranking CIA officials to the AP and Washington Post not to publish the story were rebuffed. Other high-ranking Obama administration officials, including White House chief of staff Denis McDonough and deputy national security advisor Ben Rhodes, as well as FBI Deputy Director Mark Giuliano, made the same argument to the reporters and their editors.

By the time Brennan got his warning from headquarters, however, it was too late to for him to make an appeal. The story, by the AP's Matt Apuzzo and Adam Goldman, who had recently left AP to join The Washington Post, was online.

Levinson's family also did not want the story published, according to their attorney, David McGee. "The family did not authorize them breaking the story," McGee tells Newsweek. "We assumed the AP would actually call and ask for permission."

White House spokesman Jay Carney said publishing the story was "highly irresponsible."

The AP said "publishing this article was a difficult decision." The news agency's executive editor and senior vice president, Kathleen Carroll, argued that with Levinson in hostile hands for all this time, "it is almost certain that his captors already know about the CIA connection but without knowing exactly who the captors are, it is difficult to know whether publication of Levinson's CIA mission would make a difference to them. That does not mean there is no risk. But with no more leads to follow, we have concluded that the importance of the story justifies publication."

On Saturday night, McGee called publication of the story "kind of a relief."

For years the family had known of Levinson's work for the CIA, McGee says, explaining that after Levinson disappeared, "We searched Bob's computer and found documents that connected him to the CIA. Those were not conclusive in themselves, but in those documents we found e-mails and addresses. My paralegal hacked the email accounts, and we found day-to-day back-and-forth correspondence with the CIA."

From the beginning of this mess, the U.S. government steadfastly denied that Levinson "worked for" the CIA, which is technically correct - he was a contractor. But as the years passed with no breakthrough in his case, the family chafed at suppressing the truth, and began to feel that the CIA was more interested in covering up its connection to Levinson than in finding him.

McGee says the documents he found were turned over to the Senate Intelligence Committee, which summoned CIA officials for an explanation. "They at first bald-faced lied about it," says McGee, who spent 17 years investigating organized crime in the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Northern District of Florida. "They said he had no connection with the CIA. Then [the committee] confronted them with the documentation we had, and they went, 'Oh boy, we have to go back and do an investigation.' At that point, the CIA launched an investigation."

The CIA eventually concluded that Levinson had been improperly contracted and supervised by an agency intelligence analyst, Anne Jablonski, an expert on Russian organized crime. That had been one of Levinson's specialties at the FBI when he retired in 1998 and went to work as a private investigator. Jablonski had been giving him intelligence-gathering assignments, normally the work of the agency's clandestine operators, although in the past two decades analysts have increasingly worked in the field.

A year after Levinson disappeared, Jablonski and other two other CIA intelligence officials were forced out of their jobs and seven others were disciplined for their roles in the affair. To avoid an embarrassing lawsuit, and buy the family's silence, the spy agency paid the Levinson family $2.5 million.

Why Levinson went to Kish, meanwhile, remains a mystery. But one thing is clear: He had arranged a meeting there with Dawud Salahuddin, an American convert to Islam and fugitive assassin for the Iranian regime. (Salahuddin famously stole a scene from Three Days of the Condor and dressed as a postman to murder an Iranian exile on his doorstep in a Washington, D.C., suburb in 1980.)

By some accounts, Salahuddin, an African-American who grew up as David Belfield on Long Island in New York, had grown disenchanted with the Iranian regime during his 27-year exile. Levinson was encouraged by a reporter friend, NBC's retired investigative producer Ira Silverman, to think of Salahuddin as a potential source. But for what? The CIA? The tobacco company client for which he was also investigating cigarette smuggling? Both?

If Levinson came to Kish on a CIA mission, Salahuddin says, he didn't act like it during their meeting at a hotel there on March 9, 2007. He didn't ask for inside dope on the Iranian regime. "He told me he was there on behalf of British American Tobacco, and he wanted to talk to some Iranian officials about cigarette smuggling in the Persian Gulf," he told Time magazine last week.

McGee, however, tells Newsweek Levinson had a far more risky mission: investigating high-level Iranian corruption. And that sounds like CIA work.

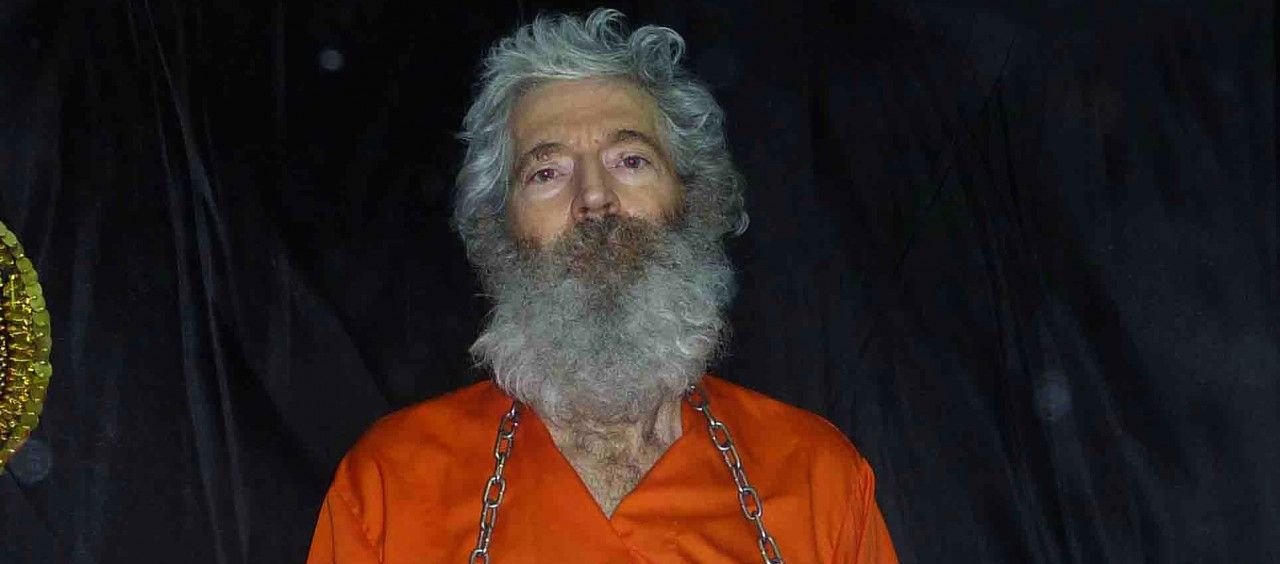

Levinson was picked up for questioning by Iranian security agents, says Salahuddin (whose accounts of meeting Levinson have varied over the years). He was not seen again until 2010, when more than a half-dozen people listed as contacts on Levinson's cell phone received a mysterious "proof of life" video in which he asked the U.S. government to arrange his release. The family responded, but heard nothing back. And then, in 2012, the family received still photos showing him gaunt and haggard with a scraggly beard, dressed in a prison-style orange uniform and holding a variety of signs begging for his rescue, including one that said "Help Me."

Washington is convinced that this quasi-CIA agent has been held by Iran all along, despite that country's denials and clumsy attempts to cast suspicion elsewhere. (In the 2010 video, for example, Pashtun music native to Pakistan and Afghanistan plays faintly in the background, as if from a radio casually left on.) At one point, however, McGee told Newsweek, the Iranians virtually admitted holding Levinson by secretly haggling with Washington over the procedures for his release, including the requirement that they would not have to admit that they'd snatched him.

Emissaries of Iran, he alleges from conversations with U.S. investigators, "demanded that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton make a statement - there were some negotiations - that he's not in Iran, that he's in some third country other than Iran" - such as the tribal areas of Pakistan. "The negotiators thought she had agreed to do that. But at the last minute, she decided not to, and said he's somewhere in Southwest Asia, which was not the statement that the negotiators had agreed on. And so that deal fell through."

"Now, I'm not criticizing the Secretary of State," McGee adds. "I understand there are a lot of reasons you don't want to allow the Iranians to pressure the United States into lying to the world, and I'm not prepared to make a moral judgment about that.

"But what that demonstrates is that the Iranians had decided that they wanted to create the impression that he was being held by someone else."

Hillary Clinton's office declined comment, but a U.S. diplomatic source cast doubt on McGee's account. A spokesman for Iran's mission to the United Nations did not respond to an emailed request for comment. Last Sunday, Secretary of State John Kerry told ABC News that he had "personally raised the issue, not only at the highest [Iranian] level that I have been involved with, but also through other intermediaries."

While McGee doesn't blame American diplomats for failing to solve the faction-ridden Iranian regime, he heaps scorn on the FBI for its role in the affair. While some agents and officials worked diligently to find Levinson and get him home, the bureau's efforts overall, he says, "ranged from neglect to insufficient to absolute obstruction."

He says the FBI has never interviewed "some of the key witnesses" with information on Levinson's whereabouts and suspected abduction by Iranian agents. "An example: the first offer we got to swap Bob came in an email from a guy named Omar," who sent the offer to several people whose email addresses were on Levinson's phone. "The FBI has never interviewed those guys about their contacts with Bob. Never talked to them."

In addition, he says, "Bob worked undercover on Iranian issues with a Russian gentleman of some dubious background [who] had been dealing undercover with Iranian nationals on very high priority issues for the CIA. The guy was perfectly willing to cooperate [and] had great information," but the FBI at first declined the offer "because he was in Canada." Only after months of pressure from the family, McGee says, did the FBI agree to interview him.

"Their efforts have been sporadic," McGee says of the FBI. "They have staffed it poorly.... For years, this was staffed by junior agents. The junior agents were controlled by management. The management limited what they could do.... Off the record they would tell us, 'We're frustrated. We can't do the things we want to do, that we think are necessary for this.' "

An FBI spokesman declined to comment, but McGee's accusations rankle a high former FBI official who was intensely involved in in the Levinson affair. "We worked it hard and we wanted so bad to bring him home," this official tells Newsweek, on condition of anonymity to discuss details of the affair, some of which remain classified. Getting Levinson back, he says, "would have been our finest accomplishment!"

Jeff Stein is a Newsweek contributing editor in Washington.