Initially perceived as President Bashar Assad's worst blunder in Syria's civil war, the use of chemical weapons by his army last summer increasingly looks like his ticket to military victory and the key to his political survival.

As a small U.N.-affiliated group of chemical weapons experts toils to maintain a tight schedule mandated by the Security Council for the destruction of Syria's chemical arms, Western diplomats and the United Nations are hard at work organizing a conference in Geneva in an attempt to end the carnage.

But critics say that it could actually help Assad win the nearly three-year war, even as he stands accused by a top U.N. official of complicity in war crimes.

Damascus says its aim in attending the proposed Geneva conference is to maintain the Assad family's 40-year hold on power. And as observers believe that the military situation now favors the Assad government, he could also seal a diplomatic victory by leveraging his cooperation with the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) team.

"Assad will continue to cooperate with the OPCW," said a Western diplomat who closely follows Syria. "He has the know-how, so he can renew the chemical program in the future if he wants it. But for now, as long as he cooperates with the chemical team, everybody has an interest in keeping him in power," the diplomat added, asking for anonymity so he could speak freely.

In November, after months of fits and starts, Secretary of State John Kerry and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov announced that Syria's warring sides will meet in Geneva on January 22. The conference, dubbed "Geneva II," is designed to follow up a June 2012 communiqué, issued by regional and world powers for a diplomatic solution to the crisis.

So far, however, no formal invitations have been issued. U.N. officials say that on December 20, U.N. Secretary-General Ban's special Syria envoy, Lakhdar Brahimi, is scheduled to meet Russian, American, Chinese, and European diplomats to finalize the list of those attending and invite them to the January conference.

But Brahimi's task is not as simple as composing a party guest list. While the Assad government has promised to attend the conference, it also said in a statement this week that "the official Syrian delegation is not going to Geneva to surrender power."

The Damascus statement, as reported by the government-controlled news agency SANA, added that "the age of colonialism, with the installation and toppling of governments, is over. They must wake from their dreams."

Yet, according to the original communiqué, known as Geneva I, a "transitional governing body exercising full executive powers" must replace the Assad government.

"We cannot go to Geneva II if the basis of the negotiations for Geneva I can't move ahead," French U.N. ambassador Gerard Araud said Tuesday. "There are others that won't go" unless the Assad government fully commits to transfer its powers to the transitional body, he told me. "If you are in the opposition, you are going to Geneva to negotiate what?"

Ahmed Jarba, the head of a Western-backed anti-Assad umbrella group, said last month his Syrian National Coalition would attend the Geneva conference. But the group also said in a statement that "Bashar Assad will have no role in the transitional period and the future of Syria."

Even the conditional agreement by Jarba's coalition to participate in the Geneva conference was too much for some members of the opposition. "Those who are going to Geneva are pushed there by force," said a New Jersey-based activist, Fahmi Khairullah, who recently resigned his post as president of the Syria First Coalition, a pro-democracy group.

He added that despite Washington's "heavy pressure" on Jarba and others to attend the Geneva conference, they should not go as long as Assad declines to end the fighting. "If you stretch your hand to shake my hand but there's a knife behind your back, what should I do?" he said.

The Syrian government's vow to maintain its hold on power could further complicate the attempt by Americans and others to find representatives of the opposition who would attend Geneva.

Washington downplays the statements from Damascus. "What do you expect them to do? They say it for public consumption," an administration official told me. A European diplomat at the United Nations added that all sides are currently toughening their positions, but "once they get to Geneva and put all together in one room, the dynamic changes."

Yet as of now it is unclear who would end up participating, or even if the conference would take place at all. Critics say that part of the problem is the premise of the conference. According to U.N. and American officials, it is convened because there is "no military solution" for the Syria crisis.

Not so, says Eyal Zisser, director of the Dayan Center at Tel Aviv University and a longtime Syria watcher. "The war in Syria will be won on the battlefield," he says, adding that for Assad "It's either victory or death."

While the balance of power currently is "too close to call," Zisser says, government troops increasingly seem to have the upper hand, while the opposition suffers from disunity and feels forsaken by the outside world.

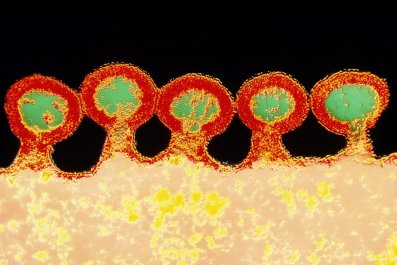

The chemical team's mission, meanwhile, shows signs of progress as America offers to destroy the vast caches of dangerous weapons on warships in the Mediterranean in a process that starts with diluting the chemicals to render them harmless. But, as Sigrid Kaag, the U.N. coordinator of the chemical destruction team, acknowledged after briefing the Security Council on Wednesday, the team is yet to resolve its security issues. Mostly, how would it navigate a chaotic battlefield while trying to transport more than a thousand tons of a volatile substance from Syrian army bases near Damascus and elsewhere to Latakia port on the Mediterranean, while rebel groups have an obvious incentive to disrupt the deliveries?

On the other hand, so long as Assad cooperates with the chemical team, no Security Council member is expected to send his case to the International Criminal Court, several diplomats told me. This issue arose Monday when the U.N.'s Human Rights Commissioner Navi Pilay cited evidence that "the highest level of government, including the head of state," is responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

U.N. officials later said that Pilay has a "sealed list" of war crime suspects in Syria, which may or may not include Assad's name.

"Did she declare herself a new prophet?" Syria's U.N. ambassador, Bashar Jaafari, said dismissively when I asked him about the human rights chief's accusation. In Damascus, deputy foreign minister, Faisal Mekdad told the Associated Press that Pilay "has been talking nonsense for a long time and we don't listen to her."

Jaafari also disputed the latest report from a London-based group that keeps casualty numbers in Syria, which said that 125,835 have died in Syria since the beginning of the war in March 2011. And he put the onus of the deaths on Jihadi rebels, who he said were financed by Saudi Arabia and other gulf states that also send fighters to Syria to join with American and European militants that have recently arrived there to fight against the regime.

"How many [of the casualties] are killed, raped, and slaughtered on behalf of Allah," asked Jaafari.

Several American officials acknowledged this week that Al Nusra and other Sunni Jihadi groups are gaining strength and dominate the battlefield much more than moderate anti-Assad groups. Al Qaeda's chief Ayman al Zawahiri recently called on the group's warriors to join the Syria battle, even as Hezbollah and Iran fight alongside Assad troops.

"Assad treats these endless skirmishes with the various rebel groups the way a farmer fights locusts: The bugs swarm all over the field and causes great harm, but sooner or later they will either get tired or disappear," says Zisser.

Washington, meanwhile, is losing its way in this fight and promotes the Geneva conference not because it really believes it could change anything on the ground, but because "it wants to show it is doing something, even while it is doing nothing."

Follow Benny Avni on Twitter: @bennyavni