Your Thanksgiving dinner could be going to your thighs in more ways than one. Since low doses of antibiotics have been used to promote weight gain in food animals since the 1950s, it should come as no surprise that America's obesity epidemic may be linked to use of these drugs.

For many years scientific studies have illustrated the connection between weight gain and antibiotics, due to their bacteria-killing action. One as early as 1954 found that Navy recruits given daily doses of penicillin to prevent strep infections gained 4.8 pounds over seven weeks compared with the 2.7 pounds gained by participants given a placebo.

More recently, researchers have focused their attention on the possibility that antibiotics could be making children fat. New Zealand researchers conducting a large international survey found that boys treated with antibiotics during their first year of life reported higher body mass index (BMI) between the ages of 5 and 8 than boys who had not been similarly treated. A smaller Danish study found the use of antibiotics in infancy increased the risk of higher-than-average weight gains in childhood. Meanwhile, New York University researchers discovered that when infants were given antibiotics before the age of 6 months, they were 22 percent more likely to be overweight at 38 months than infants who had not been exposed to the drugs. Despite the relatively small weight gains in these children, the findings are significant.

Nearly one in five American children is considered obese. While they may not face major health issues now, that could easily change in adulthood. Obese children are more likely to become obese adults with a higher probability of certain illnesses, including diabetes, heart disease, and certain cancers. And though it may appear that non-obese but still overweight children do not face as bleak a future, children with higher BMI are more likely as adults to have an increased risk of heart disease, the number one cause of death in America.

As first lady Michelle Obama and others have pointed out, overweight children are a major health concern - but can antibiotics really be blamed?

One thing is clear: Antibiotics change the makeup of your insides. In a recent French investigation, researchers discovered that use of the antibiotic vancomycin, which was developed to treat penicillin-resistant infections, could be linked to a 10 percent BMI increase - directly connected to what the authors of the study call the "gut microbiota."

Our digestive system is a group of organs, which includes the stomach and the colon, and together it harbors nearly 100 trillion bacteria - our gut microbiota. These bacteria make an invaluable contribution to our metabolism by helping to break down complex carbohydrates and starches. They are also crucial to the development of our immune systems and thwart the growth of harmful bacteria. They even produce vitamins and hormones that direct the storage of fats. Many scientists believe our gut microbiota, which weigh up to four and a quarter pounds when taken en masse, act as an organ in-and-of themselves.

But they are not the usual bodily organ. If collectively the array of organs in our digestive tract is, let's say, a shopping mall, then gut microbiota operate as a black market within its shadow. The purpose of each is much the same - both are fundamentally concerned with the metabolizing of food - but the finer details of gut flora and how they accomplish their digestive work have long escaped observation. This means scientists don't clearly understand how gut flora influence weight gain and loss.

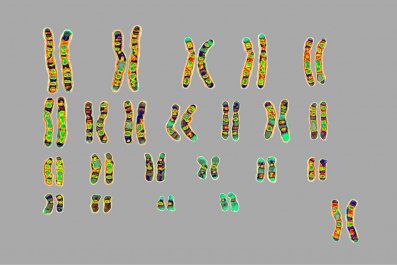

For instance, it has never been possible to culture every species of bacteria and learn what roles they perform in the gastric tract. Recent advances in genetic sequencing, though, have enabled deeper investigation and this has resulted in an explosion of information. It is now understood that gut microbiota collectively contain 3.3 million genes, a hundred times the number of human genes. Our bodies, then, host an apparently separate self - one that may, for all we know, determine how well we process our food and in so doing, regulate how much we weigh.

In order to better characterize the function of gut flora, scientists have begun to analyze individual bacterium as well as the composition of the whole in the hopes of understanding precise effects on digestion and metabolism. In one study, for instance, researchers discovered that a less diverse community of gut bacteria goes hand in hand with increased obesity and insulin resistance. In fact, obese individuals with lower levels of microbial richness tended to gain more weight than those with higher levels of microbial diversity. In another study, researchers transferred the gut microbiota from human twins into adult, germ-free mice. The twist here is that each set of twins were all unmatched pairs in which one twin was thin, the other fat. The mice receiving material from the overweight twin soon became overweight, while the mice receiving material from the lean twin remained lean.

So while some scientists are asking whether it is possible to purposefully manipulate the composition of gut microbiota to improve human health, other scientists are worrying about the unintentional manipulation of the composition of gut microbiota. The diversity of your gut bacteria is impacted anytime you take an antibiotic prescribed to cure an illness. Not only does the medicine attack the intended target, pathogenic bacteria, but it also kills some of the bacteria living in your digestive tract. So each instance of taking an antibiotic changes the composition of your gut microbiota. The million-dollar question is if this is temporary fluctuation or permanent change?

Consider that in the early 20th century, Helicobacter pylori was a microbe found in almost all stomachs, but by the turn of the 21st century, fewer than 6 percent of children in the U.S., Sweden, and Germany were still carrying the organism. In an article published in Nature, Martin Blaser suggests a compelling argument in favor of antibiotics as the reason behind this dramatic shift: A single course of antibiotics that treat middle-ear or respiratory infections in children eradicate H. pylori in up to half of all instances.

The changing ecosystem within our guts, which to a large extent may be caused by overuse of antibiotics, leads to a greater potential for gaining weight. If, as the FDA suggests, up to half of antibiotic use is unnecessary and inappropriate, then as individuals and as a society we need to seriously rethink the many ways and instances in which we use this popular and plentiful class of drug. In fact, choosing from dozens of antibiotics available, doctors currently write upwards of 150 million antibiotic prescriptions each year.

Yet the harm done may not be from the pills we ourselves directly swallow. Just short of 15,000 tons of antibiotics were used to promote growth in domestic food animals during 2011 alone. Between 1950 - when antibiotics began to be widely used to fatten animals - and 2000, obesity rates in the U.S. increased by 214 percent. Currently, more than a third of all adults are considered obese while in the past three decades the number of obese children has tripled. Yet, for all we know, the obesity epidemic may be replaced by something even worse.

Most of the antibiotics commonly used for animals belong to the same classes as human antibiotics, including tetracyclines and sulfonamides. The animals ingesting these antibiotics become fat - which we like, because larger animals mean more meat for the table - yet at the same time these animals also develop antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which they then transmit to humans through the food supply.

When these resistant bacteria enter human guts, exactly how do they interact with our own existing microbiota? The answer to this question is still unclear, but what is known is this: Whether or not these bacteria choose to colonize there, they still may cause infections and still may transfer their resistance to the other bacteria in our digestive tract. In so doing, have they transferred other properties as well? With each bite of meat from an animal treated with growth-promoting antibiotics, we very well may be developing an inability to properly digest food and an incapacity to make necessary hormones and vitamins on which our bodies rely.

Meanwhile, the danger caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria grows. Each year, at least 2 million people acquire serious infections with resistant bacteria, while at least 23,000 people die. Not only have infections from resistant bacteria become increasingly common, but some bacteria are developing resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics. This amounts to a major loss with doctors undermined in their ability to fight infectious diseases

In a speech she gave last year, Dr. Margaret Chan, the director-general of the World Health Organization, offered this dire warning: "A post-antibiotic era means, in effect, an end to modern medicine as we know it. Things as common as strep throat or a child's scratched knee could once again kill." Obesity resulting from overuse of antibiotics may be the least of our worries.