🎙️ Voice is AI-generated. Inconsistencies may occur.

"Without this, we would be in trouble," Tobias Meyer says. It's a warm October morning in New York City, and the head of contemporary art at Sotheby's is standing in front of a huge canvas depicting a horrific car crash, the vehicle gruesomely crumpled against a tree. The label reads, "Andy Warhol. Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster) 1963. Estimate upon request." The huge (8-foot-by-13-foot) canvas is, by all accounts, a masterpiece; part of Warhol's disaster series - his reflections on mortality. Nearby are other rare treasures consigned for Sotheby's all-important November auctions: paintings from the collection of Steven Cohen - the notorious billionaire hedge fund manager; a $40 million Picasso; a 56.9 carat pink diamond. Yet Meyer cannot stop thinking about that Warhol.

Few people will ever know how hard he fought for this painting - or understand how much he has riding on it. Twenty-three blocks south, in midtown, Meyer's archrival at Christie's has amassed the largest cache of art ever to come to auction - more than a half-billion dollars' worth. In an all-out battle over the summer, Christie's beat Sotheby's on consignment after consignment, snaring major trophies of the contemporary art world by superstar artists such as Francis Bacon, Jeffrey Koons, Christopher Wool, Willem de Kooning, and Jackson Pollock. By early fall, the roster for the Christie's November 12 auction was expected to sell for between $500 million to $700 million.

Just weeks before the sales were to start, Meyer had nothing that could compete with the caliber of art Christie's was bringing to market. That Warhol was his last shot at a major consignment, and as its owner wavered throughout September, Meyer flew to Switzerland to plead his case. When that didn't clinch the deal, he invited the collector to spend the weekend at his country house in Connecticut. The pressure on Meyer was enormous and mounting. And it wasn't just Christie's colossal sale weighing on him; Sotheby's largest shareholder, hedge fund manager Dan Loeb, was growing increasingly disgusted by the company's lagging performance. In an open letter, he castigated the company's management and demanded that Meyer's boss, CEO Bill Ruprecht, be fired.

"You know, I talk about the near-death experience," Meyer says, recalling his hectic summer. He tells the story of how he put his heart and soul into winning the picture; how finally - right before the print deadline for the auction catalogue - he got word that the consignment was his. Meyer pauses for a moment, mid-tale, as though to add drama to his victory. Then, suddenly, something strange happens: His chest caves deeply, as though a huge weight has been dropped on him. He holds out his hand, as if reaching for support. His voice trembles into a deep, raw sob. "Let's go somewhere else," he finally says in a hoarse whisper. Meyer - renowned in the art world for his poise on the auction block - steps behind a wall and into a side gallery where privately, quietly, he wipes a few tears from his cheeks.

Never before have the stakes been so high. Art is now a $55 billion business and the amount of money flowing through the major auction rooms is staggering: In two nights in November, Christie's and Sotheby's sold more than $1 billion worth of art. At its Contemporary and Post War sale this week, Christie's broke the price record for the most art sold in a single night - $691.6 million, and its Francis Bacon fetched $142.4 million - the most ever paid for a piece of art at auction. The next night, at Sotheby's contemporary sale, Silver Car Crash sold for $105.4 million - more than $30 million higher than the price the last big Warhol fetched. That helped Sotheby's sell $380.6 million in art - more than any other auction in its 269-year history.

The forces driving the bidding in these salesrooms right now are much bigger than either Christie's or Sotheby's - or even the art market. Over the past five years, a huge wave of global wealth has been swelling, transforming markets and industries across the globe. Since 2009, the number of billionaires in the world has tripled, to 2,170. Last year, Asia produced 18 new billionaires and is on track to pass Europe's total by 2017. Many of the new rich are from parts of the world unaccustomed to this proliferation of wealth: Brazil, China, India, and Russia. Those 2,170 people control some $6.5 trillion and each year, on average, spend $78 million apiece on real estate, $60 million on yachts, $22 million on private jets, and $16 million on art. "These are people for whom five- or ten-million dollars is like you and me buying lunch," says Philip Hoffman, president of the Art Fund, an investment pool for buying art.

Auctioneers, art dealers, and collectors tell stories of new buyers who scoop up four or five items in a single auction, spending tens of millions of dollars. A Brazilian man who had never bought a major work of art recently plunked down $67 million at his first auction. An Asian collector bought one item for $1 million last spring, then jumped to a $10 million work in the summer sales, and most recently bought something for $30 million. During the sale of a Mark Rothko painting last spring, there were 10 bidders still in the running at the $50 million mark, and they pushed the price of that canvas to $86 million. This month, at the Christie's Impressionist and Modern sale, Chinese tycoon Wang Jianlin bid ferociously for a painting of Picasso's children, Claude et Paloma - ratcheting up the bidding by $1 million increments. He finally won his prize for $28.2 million - more than double its $9 million to $12 million estimate.

All this good news is making some people nervous. "The more you are pushing the market toward the high end, the more you are raising the stakes," says Anders Petterson, managing director of ArtTactic Ltd., a London-based art market research firm. "If a work with a high estimate doesn't sell, that creates a big hole that could send a negative signal into the market." The art market is fickle, swayed by trends, personal taste, even emotions, and there are works by great artists that don't sell. Last spring, Sotheby's failed to sell a painting by Bacon that had an estimated value of $30 million to $40 million. This month, at an estate sale for famed dealer Jan Krugier, Christie's failed to sell a Picasso, estimated value: $25 million.

The only fail-proof items are the masterpieces. And that is where the arms race between Christie's and Sotheby's has turned ugly. Almost by definition, masterworks are hard to come by - but as more billionaires with open checkbooks enter the market, these items are ever more coveted. And harder to find. Most of the great Old Masters and Impressionists are claimed, and the best Rembrandts, Monets, and Van Goghs are in museums or foundations. That leaves the contemporary market, which is now the fastest-growing segment of the market. Since 2009, sales there have grown 2,000 percent, to $6 billion, according to Arts Economics, an art market research firm. Yet even here, the supply of truly great work is dwindling. It will be a long time - if ever - before the world sees another Warhol Car Crash on the market; the other three paintings in that series are in museums.

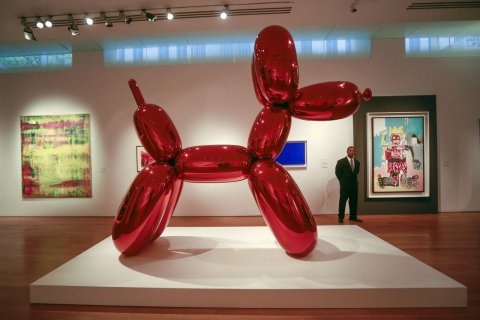

"When you walk into the auction room, there is this magic. It's like being an actor walking on stage: You feel your audience," says Brett Gorvy, the chairman and international head of post-war and contemporary art at Christie's, shortly before his big auction. Standing in a narrow gallery space at his New York headquarters, Gorvy is trying to describe the rush an auctioneer feels right before a big night. Here, he is looking at the trove for his coming November auction, which he has spent an exhausting six months gathering for this sale. On one wall hangs the Francis Bacon triptych that made headlines around the world; close by is a $58 million Jeff Koons balloon dog consigned by collector Peter Brant; on another wall is a $57 million Warhol Coke bottle, hanging next to the most valuable Christopher Wool in the world. There is also a Gerhard Richter, a de Kooning, a Pollock... and on and on it goes. The gallery is wall-to-wall masterpieces. It may be the greatest cache of contemporary art ever slated for the auction block. "We are lucky to be in middle of this incredible momentum," Gorvy says. Soft-spoken, slight, and stoop-shouldered, he looks to be an unlikely protagonist in this arms race. But Gorvy, arguably the most powerful auctioneer in the world right now, is a ruthless competitor.

Last May, in an extraordinary feat of salesmanship, Gorvy outsold Sotheby's by $200 million during the all-important spring contemporary sales, during which Christie's sold $495 million of art. At that the time, it was the most art sold at auction - trumping even past sales of Impressionist and Modern artists such as Monet, Cezanne, and Picasso. The May sale made it clear that contemporary art is now the dominant market of the art world - and Christie's its dominant auctioneer.

That sale made something else very clear to Gorvy: This market craves masterpieces, and he has made it his mission to hunt them down. His staggering triumph in May gave him the leverage to pry works from the owners of trophies, many of whom had never intended to sell and some of whom had been good Sotheby's clients. "It was a way to start the conversation" Gorvy explains coyly of his big May payday. In pursuing the Jean-Michel Basquiat painting, Untitled, he recalls that "it got complicated because [the owner] had a personal relationship with someone at Sotheby's." But Gorvy got past that because, in part, he'd sold another Basquiat for $48.8 million a few months earlier. At his November 12 sale, he sold Untitled for $29 million. "There are a lot of powerful buyers in the market now who really are looking for the best of the best," he says. They want masterpieces that will retain their value, and protect their wealth.

Gorvy's major win of the season was a rare triptych by Francis Bacon, three studies of another famous artist, Lucien Freud. The painting is a particular prize because it connects two of the great masters of 20th century art - imagine if Botticelli had painted Raphael. What's more, it had rarely been seen in public since its first showing in 1971. Its three panels were split up and sold to three buyers. An Italian collector painstakingly tracked down the panels and put them back together over several years. He had no intention of selling, but Gorvy convinced him he could get a price the work might never get again. "Now is a moment to seize," he explains. "There are a lot of powerful buyers in the market that really are looking for the best of the best."

When Christie's announced that it had the triptych, the art world thrummed with anticipation, predicting that this sale would smash records. With the Bacon, and a slew of other masterworks on its roster, Christie's lead over Sotheby's heading into the November sales was staggering: Its estimates were $200 million more than Sotheby's.

For Christie's, the fall sale is an endorsement of its new approach to the ancient art of auctioneering. "For 200 years, we had a strategy that was: If we build it, they shall come," says CEO Steven Murphy. The former head of EMI Music and Rodale Publishing took over Christie's in 2010 - the first American chief since its founding in 1766. From day one, his mission has been to push Christie's into the middle of the new global economy. Earlier this year, Christie's held its first auction on mainland China, at its new Shanghai headquarters. Six hundred Asian buyers packed the room as $25 million in art, wine, and jewelry were hawked. In December, Christie's will open its Mumbai headquarters; next year it will open an office in Brazil.

Another big part of its strategy is to lure new buyers through technology. Its online-only auctions offer lower-priced items (starting at $500) - Picasso ceramics, Diane Arbus photographs, and Warhol prints. These draw customers who might not otherwise step into an auction room: 45 percent of Christie's online traffic is new buyers. Murphy insists that the cheaper sales do not hurt Christie's high-end brand: "We have clients who want to buy a $30 million Yves Klein and Georgian candlesticks and are happy to come to Christie's for both."

At the high-end of the market, Murphy has been an aggressive deal-maker, offering big financial incentives to win big consignments. Here he has a huge advantage over his counterpart at Sotheby's: As a privately owned operation, Christie's doesn't have to answer to public shareholders about expenses or spending. Since Murphy has taken over, Christie's auction sales have increased by 25 percent, to $6.3 billion.

"I have said it three times, and now I will say it a fourth: It is not a way to run a business to run after someone else's model," says Ruprecht. Rain is pelting against the window behind him as he sits in his New York office. He is a large, avuncular man - round belly, rosy cheeks. Normally, he is warm, upbeat and charming. But on this morning, he is prickly. It's clear he is growing tired of questions about his strategy and the state of the market. "The pejorative tone is noted," he says at one point in response to a question about whether the market's prices are sustainable. At another point, his PR chief steers the conversation by saying: "No activist investor questions."

Ruprecht has had a rough couple of weeks. In early October, his largest shareholder, Dan Loeb, who owns 9.3 percent of the company, launched a personal attack against him. In an open letter he admonished Ruprecht for lagging behind Christie's, bashed him for his $6 million pay package, for using private jets and for running up a lunch tab of hundreds of thousands of dollars in one afternoon. All the while, his main rival, Christie's, had been on a rampage - swiping the top consignments and setting records at an alarming pace. Critics such as Loeb say it's time to shake things up at Sotheby's, that Ruprecht is shortsighted and is missing out on the bountiful opportunities presented by the new global economy.

Ruprecht disagrees with a shrug. "This is a business of permanent white water," he says. "There are always roiling issues." Last month, he convinced his board to adopt a "poison pill" measure that would keep Loeb from buying any more shares, and having any more sway over the company. He plans to keep his job - and stick to the strategy that's worked at Sotheby's for the past 269 years.

Ruprecht intends to continue focusing on high-end clients interested in buying items in what he calls "the sweet spot" between $50,000 and $5 million. This is where auctioneers make the most money, because the house can charge full commission prices and doesn't have to offer guarantees. Despite the headlines and massive sums masterpieces generate, auction houses don't make much money off them. High-end sellers usually demand - and get - reduced commissions, some as low as 5 percent. They also will ask for other financial incentives, such as half of the buyer's premium. "If you tilt your business toward the high-high-end, you walk home with lots of headlines," Ruprecht says, "and a challenge for how you are going to pay your staff."

On the evening of November 12, shortly before the biggest sale of his career, Brett Gorvy watches the crowd pour through the gates of Christie's. Billionaires, power brokers, and reporters from all over the world are jostling for seats or just spots to stand in the packed auction room. Some are taking selfies in front of the great works on display. Reporters scan the crowd looking for heavy-hitters who might be the night's highest bidder - Larry Gagosian? Mike Ovitz? Dan Loeb?

Everyone in this room senses that history will be made on this wintry New York night, and no one is disappointed: When the Bacon triptych goes on the block, the bids come so fast that the price rockets from $80 million to $100 million in just a few minutes. When the hammer comes down to end the bidding, the room erupts with applause, and Gorvy is smiling broadly at the crowd.

An hour later, after the bidders and spectators have gone, when asked how he felt the moment the Bacon sold for $142 million, he sighs, "I was very tired actually." Indeed, it's hard to revel for long when he knows his competitor has been watching all this, and is very likely planning for the next round of their battle. He sighs. "It's a very daunting prospect to think that come the 13th of November, everything has to start again."

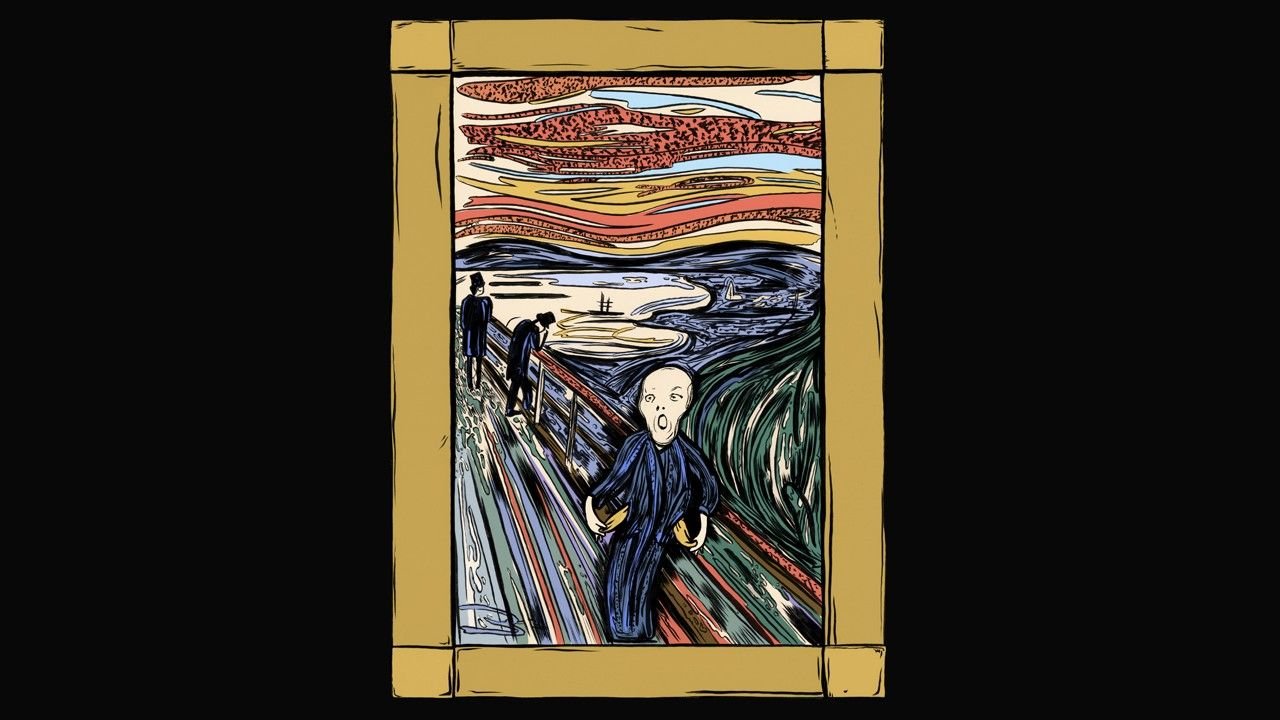

The night after his rival's colossal sale, heading into the sale room, Meyer knows there is no way he can catch Gorvy: The high estimate for his sale is $394 million - $300 million short of the Christie's mark. What he can do and what he must do is sell that Warhol - and sell it big. And if anyone is up to the task, it's Meyer. In his 21 years at Sotheby's, he presided over some of the world's biggest auctions. Last year, he sold an Edvard Munch painting for $120 million - the record price broken by the Bacon triptych.

"Let's start the bidding," Meyer says to the crowd packed into Sotheby's sale room. The wall behind him has been painted dark blue to better highlight Silver Car Crash, hanging to his right. "The bid is at $60 million. 61 million, 62-, 63 million.... " Meyer's hands fly back and forth, across the room, pointing to maybe 10 different bidders. In less than two minutes the price shoots up to $80 million - already past the artist's record. After a frenzied five minutes, it's over. "Sold!" Meyer booms as he slams the hammer down. Applause erupts. But Meyer keeps his poise. "Now Lot 17, the Agnes Martin," he says turning to the next item for sale.

Later, after as the crowd disperses, he can't hold back his joy. "I knew this would do well, I mean you saw how emotional I got about it," he says. When asked about the pressure he felt going into the auction, Meyer is reflective, "When it gets rough, I get very quiet, very calm."

His phone rings; it's a client and Meyer answers it with, "We are so happy for you!" He then walks away from reporters to do some business. For him - and for Gorvy - the hunt for the next masterpiece has already begun.