Scientists are learning more about why it can be so hard to quit smoking. Sure, nicotine is a fiercely addictive drug - but that's only part of the story. Just look at all the millions of would-be ex-smokers who keep on lighting up despite having consumed pharmacies full of nicotine patches, nicotine gum and lozenges, nicotine spray and inhalers.

What drives the habit? One answer came out just a few days ago at this year's Smokefree Oceania conference in Auckland, New Zealand. A team of researchers there reported experimental confirmation that some forms of tobacco contain an additional chemical - if not more than one - that could make the plant even more addictive than plain nicotine. "This extra chemical is an additional thing that makes smoking harder to give up," Penny Truman of the Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR) told The New Zealand Herald. "I believe if we are going to get the best smoking-cessation methods, we need to understand it."

Scientists have wondered for a while if tobacco had more than one addictive component, so Truman and her fellow scientists at ESR and Victoria University of Wellington set out to test that hypothesis. They equipped the cages of some lab rats with lever-activated systems for three different saline solutions: one of diluted nicotine, another of dissolved smoke from factory-made cigarettes, and the third one of dissolved smoke from roll-your-own tobacco. Each test animal had to push its lever an ascending number of times in order to get a dose of its assigned drug.

The rats showed a strong craving for one "reward" in particular. They were willing to push the lever about the same number of times for either the nicotine solution or the factory-made smoke, but they pushed the lever significantly more times for the roll-your-own smoke. "That is a formal proof that some tobacco substances are more addictive than nicotine [alone] is," Truman told the Herald.

It's likely to be a while before those addictive substances are identified. Cigarette smoke contains more than 4,800 chemicals, including at least 69 known carcinogens. But Chris Bullen, director of Auckland University's National Institute for Health Innovation, is enthusiastic about the new study. "It could in part explain why nicotine-replacement therapy and other [nicotine-withdrawal] products...might not be as effective as they could be," he told the Herald.

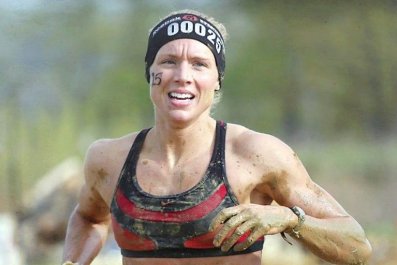

In fact, those products can be surprisingly unhelpful. According to one study published earlier this year, smokers were just as likely to fail in their efforts to quit by using nicotine-replacement therapy as they were without it - further evidence that nicotine alone is not the answer. Of course, anyone who has ever lit up can tell you that addiction isn't purely chemical: There's also the social aspect of smoking, the familiar habit of holding a cigarette or smoking in certain situations, perhaps during a break at work or to escape the loud noise of a bar or house party.

But it's far more complicated than that. Scientists have even discovered that the puzzle has a genetic component: Smoking-cessation medication gives differing levels of relief to different people, depending on their individual genetic makeup. A newly published study identified a gene that can predict whether smokers attempting to quit are likely to respond positively to nicotine-replacement therapy. The same gene also controls how quickly the smoker's body metabolizes nicotine. According to senior investigator Dr. Laura Jean Bierut, the hope is that the additional genetic information could improve a smoker's chances of kicking the habit for good.

Although the prevalence of adult smoking in the U.S. has dropped from 42.4 percent in 1965 to 19.3 percent in 2010, the number of people who manage to quit smoking remains low, according to the American Cancer Society. Within three months of quitting, seven in 10 smokers are back smoking; by the time a year is up, that number is close to nine in 10.

Truman and her team still want to determine exactly what made their experimental tobacco so addictive. If they can figure that out, they may have the key to developing a better medication for helping smokers to quit. Until then, there's just one thing to say to an aspiring ex-smoker: Keep trying. If you're motivated to quit once, you'll probably be motivated to quit again. Do it enough times, and you'll beat the addiction.