As the van revs its engine and chugs up the hill, passengers - scooped up from some of the most high-end hotels in Rio de Janeiro just minutes ago - crane their necks out and up, straining for the first glimpse of what they hope will be the most miserable squalor they'll ever see.

Suddenly, Rocinha, the biggest favela - slum - in Rio de Janeiro comes into view in all its dilapidated glory: green, yellow, white, and redbrick buildings piled on top of each other like a collapsing wedding cake, lining the base of a cliff. They see vans and cars try to squeeze through the only street, a narrow road, going up through the favela. Around them, motorcycle taxis swarm from all sides, transporting locals toward their humble residences in the heights. Rudimentary restaurants, bars, gyms, and markets dot the windy road. Electricity lines, to the tourist's surprise, create giant webs at the middle and tops of poles, a free-for-all.

On both sides and all the way to the top are endless sets of steep stairs, connecting the ever-expanding favela like an intricate circulatory system of veins and arteries.

Favelas have been demonized for decades as poor, isolated, and dangerous cities within a city. The 2002 film City of God, nominated for four Academy Awards, depicts life in Rio de Janeiro's slums as a deadly maze that few escape.

But tour agencies here say favela tours are now their most popular offerings, and they are rapidly increasing the number of tour guides and vans. According to www.tourismconcern.org, about 40,000 tourists visit favelas in Rio de Janeiro every year. Touring the slums of Rio has become, they say, as much a rite of passage as visiting the famed statue Christ the Redeemer perched atop a mountain overlooking much of the city.

On a recent afternoon, travelers from as far away as Norway, China, Australia, and Puerto Rico were taken around Rocinha, home to about 100,000 people, for only $35. They mostly stayed inside their air-conditioned van, barely interacting with the locals, except to purchase a small acai berry treat at the market.

When the tourists got out of the van, it was mostly to take pictures; they posed for solo and couple portraits, with swarms of electricity lines and shirtless children in the background.

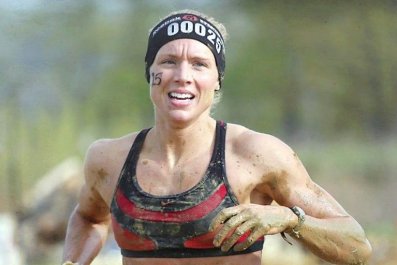

"I had always heard about favelas and was curious," says Karen Calvesbert, a golfer from Puerto Rico. But, she said, the fascination is surely one-sided, with slum dwellers likely annoyed at the hordes of tourists making their way up the hill to see their wretched lifestyle. "They probably think: Look at these stupid gringos."

Poverty tourism is nothing new. In Cape Town, South Africa, tour guides will take curious travelers to visit townships. In Mumbai, India, visitors can pay for slum walking tours. In Rio, the business is likely to grow significantly in the coming years, with Brazil expecting a major increase in tourism for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics.

The industry of poorism, as it is sometimes called, is constantly criticized for filling the pockets of a few while disregarding the negative impact it has on slum dwellers. Moisés Antonio T. Alves, executive director of the Association of Dwellers of Vidigal, another favela in Rio de Janeiro, wishes ogling tourists did not look at him and his neighbors as though they were wildebeests being tracked on a safari.

But not everyone directly involved in the poverty industry sees it that way; some even defend poorism as educational and nonintrusive. "I always say, do you think rich people in Leblon are bothered when you walk in their streets," says Axel, the French tour guide leading the group in the bus and on brief walks, referring to one of the most exclusive areas in the city.

Axel stopped frequently during his tour to give brief explanations on the history of the favelas, emphasizing that most were impenetrably dangerous two years ago, before the government went in to dozens of them to "pacify" them in anticipation of the World Cup and Olympics. He also talked about the community dynamics inside of them - "You will not find a grandmother alone, dying in a living room" - and briefly brought up the perception Brazil's middle class has of them.

"Dangerous, dirty, blah-blah-blah," he said, matter-of-factly. Perhaps in an attempt at redemption from the misery-as-entertainment visit, the tour includes a quick stop at an after-school camp for favela children, which, the guide says, is partly funded by the favela tourists.

For many Rio tourists, poverty is as seductive as the women in thong bikinis. "The favela has its own bank!" exclaims Yu Ning, a tourist from China.

"And you have a shopping center! Havaianas!" says his friend, referring to the omnipresent sandals featuring a tiny Brazilian flag that are adored by both Brazilians and tourists.

As the van makes its way back to the hotel-lined beaches of Ipanema and Copacabana, Ning looks up from his iPhone, where he has been flipping through the photographs he took during the tour, and notices a lush golf course.

"I want to play here," he says with a smile, that world up above, closer to the clouds, already far behind him.