It's a crisp, sunny Sunday morning in central London. The hall in Red Lion Square is packed.

Onstage, a choir belts out a rousing anthem while members of the congregation sing along, waving their arms and swaying gleefully in time to the music, led by a wholesome-looking young woman in a smart black dress. At the foot of the stage a young man with a thick beard and intense spectacles prepares to boom out his messages of love, joy, and hope to the world.

If this sounds like a revivalist meeting, it certainly feels that way, except that the congregation, crowding the floor and balconies of the Conway Hall, are all outright atheists, agnostics, or humanists of some other variety, and the songs they are singing with such enthusiasm are life-affirming rock standards: "Don't Stop Me Now," "Uptown Girl," "I'd Do Anything For Love."

This is the Sunday Assembly, a regular gathering for nonbelievers where the somber grandeur of organ music and Hymns Ancient and Modern have been ousted by Queen, Billy Joel, and Meatloaf. And with a tour of America opening in New York on November 4, the movement is going global.

I first read about this group when I was working on the draft of a novel. A Man Against a Background of Flames is a satirical thriller, an anti-Da Vinci Code, if you like, in which I imagine the discovery of a suppressed sect of "observant agnostics" from the late 16th century. When their ceremonies and philosophy are brought to light, they begin to attract followers, launching a god-free cult which soon spreads around the world. Implausible? I certainly thought so (it is a thriller, after all), until I discovered that something surprisingly similar was happening in real life.

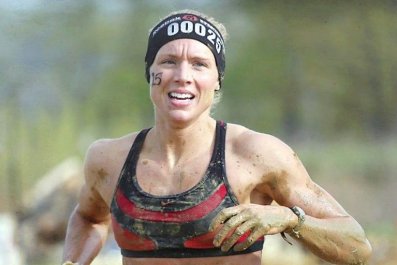

The Sunday Assembly started in early 2012 when two ebullient stand-up comics, Pippa Evans (of the smart black dress) and bearded, bespectacled Sanderson Jones decided to hold a meeting in a disused church in north London. The fact that this building was available in the first place tells its own story.

According to some polls, church attendance in England has halved since 1980, from the already low figure of 11 percent of the population (though this year the Church of England report that their attendance figures are "stabilizing"). Yet, while Anglican clerics preach to handfuls of aging regulars, the "practicing" atheists attracted a first gathering of 100, which doubled within a month. Now 300 attend regularly - and sometimes more.

A little press coverage and the magic of social media has seen new branches opening in at least 14 cities in the U.K. and Ireland. As the word crossed the pond, groups all over North America began to form. The North American "Road Show" will hold Sunday Assemblies in such cities as New York; Boston; Washington, D.C.; Nashville; Chicago; San Francisco; Los Angeles; and Vancouver, before touring five cities in Australia. More than 800 people have already signed up for the L.A. event.

When he read about the movement, Bill Maher joked online that "The whole point of being an atheist is that you don't have to go to church!" For these people, at least, he may have got that spectacularly wrong.

In my novel, I imagined that my rediscovered movement tapped into unsatisfied yearnings. As a lapsed Anglican returning to church for midnight mass one Christmas, I realized how much I missed the aesthetics of worship, the beauty of England's mediaeval churches lit by candles, the whiff of incense and above all those spine-tingling hymns and carols. There is something viscerally thrilling about singing in a large group, and for an hour or two you feel wrapped in the cocoon of a warm, benevolent community.

It turns out Pippa Evans felt exactly the same way. "I went to Church of England Church until I was 11, but my friend went to Baptist church and that was way more fun, so I started going there.

"They had a band and a choir and electric guitars and drums, and people put their hands in the air. I loved it. When I left I didn't miss God, I just missed church!"

Sanderson Jones was not brought up attending church but records a similar experience: "About six years ago I left a carol service, and I thought, So many things are so great about this. I love the singing, the getting together, the thinking about improving yourself and helping other people, but it's all centered on something I don't believe in.

"How cool would it be if this happened for something I do believe in? I think that life is so overwhelmingly fantastic that life should be celebrated just for the privilege of having it."

This message is echoed throughout their events, that the joy and wonder of life should be experienced all the more intensely because there is no afterlife. Death is final, but not to be feared, nor anticipated as a realm where some divine being will put right the injustices endured in life.

The motto of the movement, invented by Jones, is: "Live better. Help often. Wonder more". Instead of sermons, speakers tell of profound experiences which made them treasure every moment of life, or scientists explain some awesome new cosmic discovery in chirpy, accessible terms.

On the face of it, the phenomenon might seem easier to understand in Britain than America. The 2011 census recorded 25 percent of Britons having no religion, compared with a recent poll showing only 6 percent of Americans describing themselves as "atheist" or "agnostic". In one recent survey, two thirds of U.K. teenagers said they did not believe in God.

The once official Church of England (parent church to America's Episcopalians) was founded in 1533 when King Henry VIII replaced the Pope as head of his kingdom's church so he could grant himself a divorce. Afraid of civil war, his daughter Elizabeth I deliberately allowed this new and potentially explosive royal responsibility to become, for the time, the broadest of "broad churches," embracing virtual Roman Catholics and virtual Puritans. To this mix, history has added zealous evangelicals and some priests who seem to be borderline agnostics.

The English in particular have a relatively relaxed attitude to religion, regarding it as a private matter. It is considered "bad form" to force it into conversations, and many who consider themselves religious are extremely flexible about what they actually believe. Few British Christians, or Jews for that matter, believe in the literal truth of the Old Testament or Torah.

Charles Darwin is seen as a national hero rather than an agent of Satan. Most Brits are as bemused by fundamentalists' clinging to "creationism," "young earth theory" and "intelligent design" as CNN's Piers Morgan is by many Americans' resistance to any form of gun control.

British politicians often like it to be known if they are observant Christians, but they usually play it down, and few ever mix their political beliefs with their religious convictions.Tony Blair talked openly about his faith and was roundly mocked for it.

Clearly this is a major difference with America. There is a telling scene in season 7 of The West Wing when the Republican presidential candidate, Arnold Vinick, complains that all candidates for high office have to pretend to be devout, even when they are not.

Is this the view of smartass Hollywood liberals or did the writers hit a nail on its head? Probably the latter. Ian Dodd, organizer of the Sunday Assembly in L.A., points out that of the 535 legislators in the House and the Senate, only one, Kirsten Sinema of Arizona, has declared herself as having no religion.

The idea that it is more difficult to declare publicly you are a nonbeliever in America is endorsed by Greg Epstein, the Humanist Chaplain at Harvard University, who says that many students come from communities where open atheism is regarded with bemusement, shock and even hostility. "Many of the groups I talked to in America told me that admitting you do not believe in God can be as difficult as coming out as gay," says Jones.