Each night, most of us willingly, eagerly slide into a near-death state. Okay, call it sleep. But just because it happens all the time, doesn't mean it's not strange, even dangerous. It seems like pretty bad evolutionary design to have to be defenseless for a good chunk of your lifetime, but evolution usually doesn't get things wrong.

We know sleep is important - dolphins have developed a system in which only half their brains sleep at a given time to ensure both safety and sufficient zzz's - but we don't know why. For years, researchers and philosophers have wrestled with this question, coming up with theories ranging from the adaptive (we sleep so saber-toothed tigers don't eat us while we stumble around blindly at night) to the restorative (we sleep so our bodies can replenish all the stuff it used up during the day). Alas, these notions, while compelling, don't match what happens in the brain during sleep.

The mystery may be solved. A recent study finally reveals the science behind why we sleep, and it has experts dusting off words like "landmark" and "game-changing."

The story begins in the daytime. Your daily experiences - living, essentially - put your brain under enormous stress. It must absorb, interpret, analyze, itemize, concretize, and process all the data pummeling it. Tough job. Big job. Important job. And since all of that information must get cataloged, the brain needs a way to keep the important parts and get rid of what's unnecessary. Researchers from the University of Rochester Medical Center suggest sleep may serve that function.

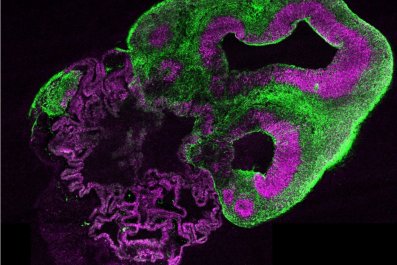

Led by URMC postdoctoral fellow Dr. Lulu Xie, the research team injected dye into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of lab mice to see how fast the dye moved through the fluid both when the mice were in conscious and unconscious states. The results were astounding. Brain activity in the sleeping mice was diminished (no surprise), but so was the dye's transportation through the CSF. The dye had a harder time making it through the fluid of unconscious mice than through that of the waking mice, whose CSF offered a clear pathway around the brain tissue.

{C}{C}{C}{C}{C}{C}

Of course, we humans don't have dye coursing through our brains. We have a substance far more sinister: amyloid plaques, proteins that build up over time and that, for years, have been the prime suspect for what causes Alzheimer's. Beta-amyloid plaques must be removed from the brain, or they gradually clog healthy pathways, degrade the neural connections within the brain and collapse the neuron's transport system. Scientists now believe sleep is the only way to adequately fight beta-amyloid buildup.

"When you're awake, it's like all the streets of Manhattan being clogged with vehicles, as they are during the daytime," says Dr. Charles Czeisler, director of the Division of Sleep Medicine at Harvard University Medical School. "The garbage trucks cannot clear the garbage efficiently. And what they've shown in this study is that those 'garbage trucks' can only clear about 5 percent as efficiently as they can clear during sleep."

In other words, sleep is when your brain takes out the trash.

"The brain has limited energy at its disposal, and it appears that it must choose between two different functional states - awake and aware, or asleep and cleaning up," Dr. Maiken Nedergaard, the study's lead author, said in a statement. "You can think of it like having a house party. You can either entertain the guests or clean up the house, but you can't really do both at the same time."

Unlike the rest of the body, which uses the lymphatic system to help cycle and flush various fluids and fatty acids from tissues and areas of the digestive system, the brain has its own ecosystem. Scientists call it the glymphatic system, and it relies on brain cells, called glia, shrinking in size to allow the CSF to more easily pass through it. In Czeisler's metaphor, the glymphatic system is what allows the traffic to disperse, clearing the way for garbage trucks to rumble through. But because of the blood-brain barrier, the fluid needs a way to move through to the rest of the body, so it piggybacks on surrounding blood vessels and circulates throughout the body, ultimately finding its way to the liver, where it will be removed as waste.

This outlines sleep's basic role, but it also illuminates a more pressing question, namely: Does less sleep raise a person's risk for cognitive decline?

Czeisler says it does: "We know that these by-products, like many metabolic by-products from burning energy, are toxic. The by-products produced when neurons burn energy are toxic to those neurons and they have to be cleared out, and they are cleared out 20 times more efficiently during sleep. We've known for years that patients with Alzheimer's disease have disturbed sleep. And this article, for the first time, suggests that this could be part of the causal pathway."

Many experts have already declared this finding to be groundbreaking, and it could be the start of a revolution in brain science. "When I say 'landmark,' " Czeisler says of this research, "I'm presuming that it is replicated - and not just replicable in a rat. If it turns out to be true across animal species, then it would have revealed the fundamental functions of sleep."