This may be hard to believe, but even Kickstarter has its limits. True, the crowdfunding website has so altered modern life that the name has become shorthand for any pass-the-hat online platform, as in "You know GiveForward? It's like a Kickstarter for killer medical expenses, like liver transplants," or "Offbeatr? Think Kickstarter, only for porn." But as the growth of those alternative sites implies, Kickstarter isn't meant to raise cash for every scheme. For one thing, the site's guidelines specifically rule out investment pitches to develop "pornographic materials" - and they also forbid solicitations for causes of any sort, no matter how worthwhile.

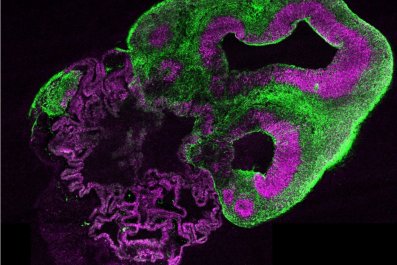

Kickstarter also demands tangible results - and that can be a daunting challenge for scientific researchers. "Everything on Kickstarter must be a project," the guidelines say. "A project is something with a clear end, like making an album, a film, or a new game. A project will eventually be completed, and something will be produced as a result." Science seldom works that way - most research efforts yield nothing more substantial than the publication of an article in a journal, if that. Failure is an everyday thing for every scientist. The data don't coalesce; the drug doesn't work; a rare species stubbornly refuses to show itself in the wild.

The good news is that science-specific crowdfunders have begun filling the void. With names like Petridish.org and Microryza, online innovators are willing to embrace the abstract nature of most scientific investigations. And the need has never been greater. Budgets are crumbling at America's proudest bastions of research support, like the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation and NASA. "There are more and more ideas out there, and there isn't enough money to support them," says Cindy Wu, co-founder of Microryza.

Not that Kickstarter ignores the sciences. Earlier this year the site actually helped the private backers of the planned Arkyd space telescope to drum up more than $1.5 million. Other recent undertakings have been successful, if somewhat less dramatic, such as an illustrated field guide to slime molds. But the main difference between Kickstarter and, say, Microryza, is that the latter site's rewards are almost entirely intangible. "For science, the actual output is more knowledge," says Wu.

The idea for Microryza fell on Wu like a virtual apple. She and her co-founder, Denny Luan, met as undergraduates at the University of Washington, where they were members of the school's synthetic biology team. A few years ago their team earned a gold medal in a national science competition by modifying a harmless E. coli bacterium to attack the anthrax pathogen. But Wu hit a wall when she tried to raise funds to test the technique against the antibiotic-resistant infection known as MRSA. "The current research system doesn't fund researchers like you," Wu recalls her professor saying.

The professor managed to scrape up the cash for her, but Wu began pondering a larger problem: how to fund research when money is scarce. She spoke with more than 100 scientists and found that just about every one of them had some bright idea sitting on the shelf, unable to attract financial backing. In some cases the researcher had a good academic record, but the idea was deemed too speculative; in others the idea was solid, but the researcher was young and unproven.

Wu and Luan launched Microryza a year ago. It has been a godsend to some fledgling researchers, but it's no less useful to established scientists: Its most effective offering to date was a study by Bisakha (Pia) Sen, an assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who raised more than $22,000 to examine the effects of state gun-control policies on firearm death rates, crime rates, and children's access to guns.

Sen credits her campaign's success to help from Wu and others and to the media attention it drew. The publicity wasn't just luck: Sen says she spent at least an hour every night for several weeks cold-emailing every journalist and columnist she could find. She calls it "an uphill battle" and advises other researchers to set lower targets, say $5,000 or so. Crowdfunding is no substitute for a federal grant, she says: "This is probably better for grad students and small projects. This is not the solution to the NIH cuts." For now, however, it beats no help at all.