At Feltonville School of Arts and Sciences, a middle school in a poor neighborhood of Philadelphia, the school year began chaotically as budget cuts took effect. Lines of kids snaked out the door while a single school secretary tried to ensure the 600 or so students attending were registered. Classrooms were packed to their limit of 33; some even spilled over.

This year, with the cuts meaning no school nurse or counselor, teachers fill the gaps, disrupting lessons to help students in distress. And the problems are not small: A boy was stabbed in the head with a pencil by a fellow student; a girl reported sexual assault by an uncle; another refused to speak after the brutal murder of a parent. And that was just the start of the school year.

"I had a kid in class today who threatened to slash her wrists with a broken ruler," said Amy Roat, an English as a Second Language teacher at Feltonville, "Most of us can't even prepare lessons because we're using all our time counseling kids." To make matters worse, budget cuts are hurting essential academic programs. Feltonville eliminated two math teachers, two science teachers, and a literacy teacher this year. Now many students who used to get 90 minutes of math instruction a day, only get half that.

Across the United States, whether it's schools, food stamps, health care or entry-level jobs, the young are feeling the brunt of government cutbacks. With debt and public spending at the top of the Republican agenda, with the sequester already biting, and with GOP members pledging not to raise revenue through taxes in any circumstances, there has never been a worse time to need help from the government.

This year, the young and vulnerable especially have been hit hard through automatic federal spending cuts to programs like Head Start, nutrition assistance, and child welfare. Financial crises in cities like Philadelphia and Detroit have meant another wave of school budget cutbacks. And the weak job market is hurting the youngest workers most, with youth unemployment more than double the national jobless rate.

This is not just an American problem. In Europe, too, austerity budgets are pinching even basic education and health needs. A decrease in the amount of money for fundamental social programs that have been in operation since World War II is widespread across the developed world.

As governments strain to cover budget shortfalls and placate debt fears, the young are losing out. "We're underinvesting in our children," said Julia Isaacs, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute and a child policy expert. "Looking at future budget trends and the fact that Congress doesn't want to raise taxes, I can see children's programs continuing to be squeezed."

That has implications for long-term economic growth. Cutting back on the young is like eating the seed corn: satisfying a momentary need but leaving no way to grow a prosperous future.

The debate on Capitol Hill, fired by Americans who have become skeptical of the value of federal spending, is all big-picture economics. It is a principled debate about where government starts and ends. It is to do with individual liberties versus communal action.

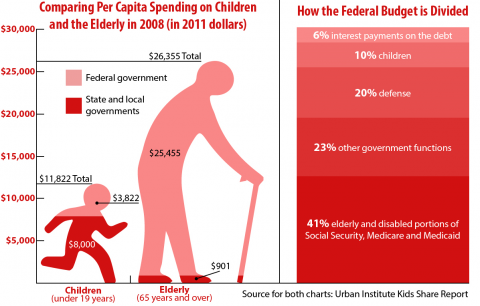

But is America overspending on its young? Public spending in the U.S. on children came to $12,164 per child in 2008, in current dollars, according to Kids' Share, an annual report published by the Urban Institute. Of that total, about a third came from the federal government and two thirds from state and local governments.

Compare that to what we spend on the elderly, which primarily comes from the federal government. According to the Urban Institute, public outlays on the elderly, in current dollars, was $27,117 per person in 2008, more than double the spending on children.

The trend is the same across the developed world. Julia Lynch, a political science professor at the University of Pennsylvania, studied 20 countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development between 1985 and 2000 and found each spent more public funds on the elderly than on the young.

But there were large differences among them. She found the most youth-oriented welfare states were the Netherlands, Canada, Australia, and in Scandinavia, while the most elderly-oriented were Japan, Italy, Greece, the U.S., Spain, and Austria. Somewhere in the middle were Germany, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Portugal.

For all the talk about needing to cut spending to save our children and grandchildren from paying off our debt, in practice we are already ignoring our children so we may remain comfortable deep into old age.

Since the 1960s, federal spending on kids in the U.S. had been rising. That trend ended in 2011, when it dropped by $2 billion to $377 billion. A year later the figure plunged even more - by $28 billion, or a 7 percent decline. And spending on kids is projected to shrink further over the next decade. The Urban Institute has forecast that federal spending on kids will decrease from 10 percent of the federal budget today to 8 percent by 2023.

That decline will occur even as federal spending is expected to increase by $1 trillion over the same period. In other words, kids are not expected to benefit much, if at all, from a big jump in federal spending forecast over the next decade. "There's concern about the growing gap between the rich and the poor," said Laurence Kotlikoff, a professor of economics at Boston University and co-author of The Coming Generational Storm, "But we've got another big problem: the growing gap in spending on the young versus the old."

Federal spending has increased dramatically for the elderly - but not for the young. According to the Urban Institute, while the children's share of the domestic federal budget has declined 23 percent during the past 50 years, non-children spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid has more than doubled. Today, an elderly person gets about seven federal dollars for every one dollar given to a child.

And while the elderly population is roughly half the size of all children in the U.S., taxpayers spend three times as much for them as they do on the young.

So, what is the federal government spending on? The budget can be roughly divided in the following way: 41 percent goes to the elderly and disabled portions of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid; 20 percent to defense; 10 percent to children; 6 percent to interest payments on the debt; and 23 percent to all other government functions. So if spending on kids does fall to 8 percent of the federal budget, and if interest payments rise along with higher interest rates over the same period, the federal government soon will be spending more on interest payments on the debt than on children.

Such cutbacks hurt low-income kids the most. That's because federal spending on kids tends to target those in need with programs like Medicaid and food stamps, while state and local spending focuses on education. Isaacs has calculated that disadvantaged children get about twice as much per capita as those who are better off. So cutbacks on kids are exacerbating the gap between rich and poor, and the two issues are now firmly intertwined.

What's driving government cutbacks? Much can be tied to fears of rising national debt. Paradoxically, advocates of debt reduction and fiscal austerity claim they are acting in the interest of the young; our debts seem be too onerous for the next generation. But in a hypercompetitive global economy, nations investing today in the well-being and education of the young are writing the success stories of tomorrow.

Of course, the U.S. is investing in education. Roughly 65 percent of all public spending on kids is on education, and that's done primarily through state and local governments. But whether it's early childhood education, elementary, middle, or high schools, or universities and colleges, fewer resources are going into public education. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of teachers employed in kindergarten through year 12th grade, principals, superintendents and support staff, fell 2 percent between 2009 and 2011 while enrollment was steady. According to the National Center for Educational Statistics, total public elementary and secondary enrollment in the U.S. is projected to set new records every year from 2011 to 2020.

The trend of putting fewer resources into public education is even more pronounced at the college level. Take the University of California for example: The average annual student charges for resident undergraduates have increased 275 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars since 1990 to 1991, while the university's average per-student expenditures have decreased 25 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars over the same period. So as California students pay much more for their education than their parents did, they're getting less. Not long ago, residents of California could attend college virtually free.

Back in the 1960s and 1970s the state's residents mightily benefited from low-cost college education. Without huge student debts, students were free to experiment with new ideas and start their own businesses. The rise of Silicon Valley as a place of innovation, creativity, and risk taking, coincided with two generations of students going to college in California for next to nothing. That might have been tougher to pull off had they been saddled with a $100,000 or so in student debt.

Throughout the current downturn, unemployment has dogged the workforce. The hardest hit have been the young. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, unemployment for 16-to-24-year-olds in July was 16.3 percent. That compares with our national jobless rate of 7.3 percent. And there are also large numbers of the young who are underemployed. Gallup recently found that only 43.6 percent of Americans between the ages of 18 to 29 had a full-time job in June 2013.

In Europe, the toll has been even heavier on the young. In the Eurozone - those countries that share the euro as currency - the youth unemployment rate is 23 percent; in Spain it has reached more than 50 percent and in Greece more than 60 percent. According to the OECD, 26 million young people in rich countries are not employed, in school or being trained, while those who do have jobs are vulnerable. One third of young workers are on temporary contracts.

High youth unemployment has implications for future earnings power. Economists who study the labor market have found that people who graduate school without a job are likely to have lower wages in their career. Some have calculated the wage penalty to be as high as 20 percent over the span of 10 years.

Even when the young land a job, investment in young workers isn't what it used to be. Training and education used to be part of any full-time job. Companies like General Motors had their own training school called the GM Institute from which they filled their management ranks with some of the brightest minds. The GM Institute became the Kettering University, and the affiliation with GM ended some years back.

Now, while global companies like Google advertise staff training, they tend to be the exception. Most companies have cut back over the years as corporate budgets are reduced and companies believe they can buy talent rather than grow it. According to a study by Peter Cappelli, a professor at Wharton Business School, in 1979 young American workers got an average of two and a half weeks of training a year. By 2011, that figure had fallen to 21 percent. As the cost of job training and education is increasingly borne by the individuals, it's harder for employees to advance to higher-paying, elite positions.

Whether because of government cutbacks or falling business investment, the young are facing tougher prospects than did their parents. And that raises vexing questions about the future. Starting with the youngest, without solid nutrition and basic health care, children can't become engaged and active students. Without resources to teach and a secure support system, public schools can't turn out educated, smart kids.

With the costs of college rising beyond the reach of many, large groups are being left behind. And with entry-level jobs and training scarcer than ever, the human capital necessary to grow America's huge economy isn't being developed. The burden on today's young to support an aging society will grow - even as the resources they are provided don't.