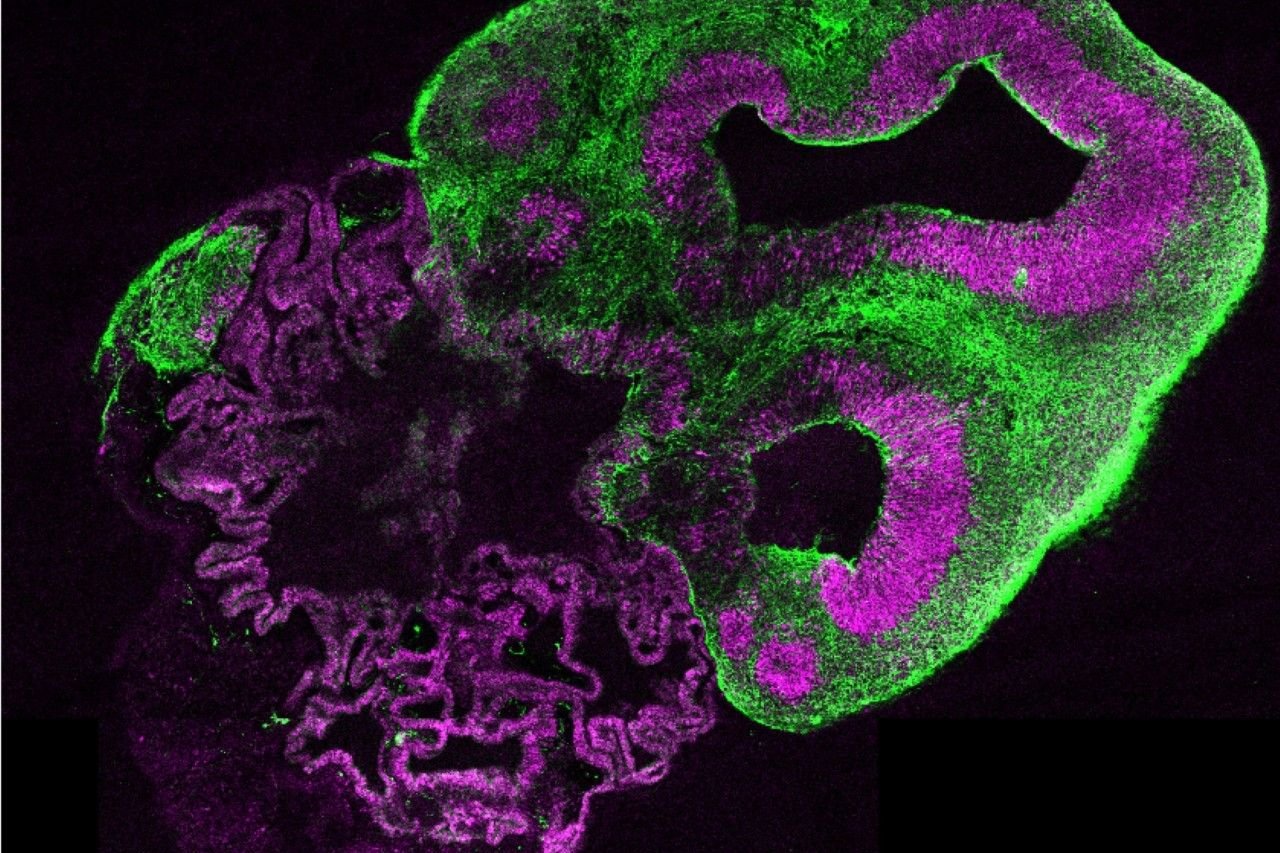

You'll never think of the word pinhead the same way again.

Scientists at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology in Vienna are growing tiny, human brain-like creations that have the equivalent developmental growth of the nascent noodle in a nine-week-old embryo. Think of them as test-tube micro-brains.

These cerebral organoids, as scientists call them, grow no larger than four millimeters, about the size of, yes, the head of a pin. The team made the first of them by taking neural tissue from embryonic stem cells and combining that with something called Matrigel (imagine petri dish Jell-O) to give the cells a structure in which to grow. The resulting little organs have the potential to help model neural problems in their earliest form, or to act as subjects to test the safety of drugs.

The head of the laboratory that carried out the project, Juergen Knoblich, tells Newsweek, "If you leave the cells alone and you don't manipulate them very much, they have this enormous capacity to organize themselves and to form really complex tissue [similar to] what's actually going on in a real developing animal or human." He adds that these Franken-brains don't have the same structure a real human brain does, comparing it to a car that is constructed with the parts in all the wrong places.

Already, the scientists have used this breakthrough to better understand a disease called microcephaly, which causes about 1 percent of babies to be born with a much smaller-than-average brain. Using skin cells from a patient with this disease, they were able to grow and analyze organoids that modeled the early stages of microcephaly. Dr. Christopher Walsh, head of medical genetics at Boston Children's Hospital, says these tiny test-tube brains are better at modeling this disease than a mouse brain, which is commonly used as a proxy for the human brain. Walsh adds that these organoids could be useful for studying neural disorders like epilepsy.

The natural question that comes to a full-sized brain after hearing of this research is: Could these creations have any kind of consciousness? The answer, says Knoblich, is a decisive no. "We do know that the neurons that we have in these organoids are active" and they "talk to each other," he says. But "there is absolutely no way that at this stage of development they would form any kind of meaningful circuit that would process information in any way."

So while these micro-brains have intriguing research potential, there's no need to worry about what they dream about when scientists turn off the lights.