The first sign of her daughter's potentially fatal illness appeared on Mother's Day.

Initially, Tonya Rerecic wasn't concerned. Addie, her 11-year-old, seemed tired - not a surprise for a kid who participated in plenty of sports. Then, a week later, Addie complained of hip pain. A trip to the emergency room revealed a bacterial infection, and she was sent home with instructions to take a pain reliever like Advil. No effect, and Addie's condition worsened until May 19, 2011, when Tonya called an ambulance to take her to the hospital. She wouldn't return to her Arizona home for five months.

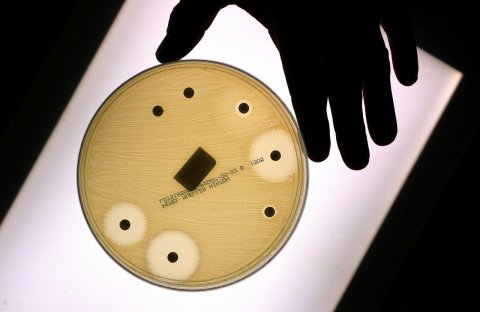

The doctors found a staph infection, which began as an abscess on a hip muscle, entered her bloodstream and spread to her lungs. Within 24 hours, Addie was hooked to a breathing machine, but soon her lungs began to fail. Usually, doctors would kill the microbes by turning to antibiotics, but that wasn't a safe option in this case. The bacteria ravaging Addie's body was resistant to most common and safe antibiotics. The only remaining possibility - Colistin - is rarely used because it can damage the kidneys. But, desperate and with no other choices, the doctors prescribed it.

The potentially toxic antibiotic, a surgery to remove the infected abscess and a lung transplant rid Addie of her infection, but not until the resistant bacteria wreaked an awful toll. The young girl suffered a stroke. She left the hospital in a wheelchair, her left arm no longer usable and her left leg impaired. The tubes and treatments had scarred her body. Her vision in her left eye was almost gone. The onetime athlete could no longer turn herself in bed. She will need medical therapy for the rest of her life.

As recently as a decade ago, Addie's story would have been a shocking anomaly, the kind of case that comes along once in any doctor's life.

But after years of futile warnings from scientists that overuse of antibiotics was causing bacteria to evolve into strains resistant to drugs, experts in the field say we have reached a tipping point, and some deadly pathogens are becoming incurable. "We are confronting one of the gravest threats to public health that we have ever faced,'' said Dr. Lance Price, a professor at the George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services who specializes in studying resistant bacteria. "We are entering a place we don't want to be, with people dying of infections that could have treated in the past."

The signs of the growing crisis are rampant. Dr. David Relman, a professor of medicine, microbiology and immunology at Stanford University, says drug-impervious infections were unusual and noteworthy not long ago. But in April, when he asked a group of student doctors at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City if they had ever come across a bloodstream infection that was untreatable by any active drug, "most of them raised their hands."

Just last month, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a stunning report on the impact of resistant bacteria. According to the analysis, which CDC officials said was conservative, more than 2 million people are infected in the United States each year by bacteria that are resistant to a wide array of the safest and most effective antibiotics. Of those, at least 23,000 die. The illnesses and deaths cost society some $55 billion annually - $20 billion from additional health-care spending and $35 billion from lost productivity.

"If we are not careful, we will soon be in a post-antibiotic era," said Dr. Tom Frieden, the director of the CDC. "And for some patients and for some microbes, we are already there."

Gonorrhea, for example, has progressively developed resistance to drugs. A strain of bacteria called Clostridium difficile, which causes life-threatening diarrhea, is now resistant to drugs commonly used for treatment, and is killing people throughout North America and Europe. Another bacteria, carbapenem-resistant Eterobacteriaceae, can cause untreatable bloodstream infections.

Resistant bacteria spread not only with cross-contamination from people who are already sick or unknowingly carrying the microbes; they also come from food Americans eat. Indeed, a current multistate outbreak of a multi-drug-resistant strain called Salmonella Heidelberg was traced to Foster Farms brand chicken. As of October 11, the microbe had infected 317 people in 20 states and Puerto Rico; 133 of them required hospitalization.

And a hospital is one of the worst places to be for someone hoping to avoid a resistant infection. Many of these deadly microbes are commonly found in medical facilities, and hospitals are scrambling to decrease the danger to patients by adopting stringent standards for disinfection and touching patients. "I would be scared to go into a hospital these days as a patient with a serious illness that might require a long stay," said Dr. Barbara Murray, director of the Division of Infectious Disease at the University of Texas Medical School at Houston and the current president of the Infectious Disease Society of America.

Murray has seen the wreckage caused by resistant strains. A few months ago, she consulted on a case of a woman suffering from a resistant bacterial infection of her gall bladder. There were no antibiotics that could treat her; with no options, the patient was sent to hospice so she could die comfortably. A plastic surgeon she knows also had a horrifying case: A knee replacement implant in a patient had collected untreatable bacteria. Doctors were forced to amputate the leg to prevent the infection from spreading any further.

In the past, drug-resistant bacteria were relatively easy to confront, with pharmaceutical companies pumping out ever-more sophisticated antibiotics. But no more. Big Pharma isn't investing much time or effort in these lines of treatment these days - why commit hundreds of millions of dollars to research and develop a new antibiotic that will be just one of many and will only be taken by a patient for a few days, when a breakthrough drug for, say, diabetes could be both unique and used by people for a lifetime?

"We have an increasing antimicrobial resistance across the world and we have a decreasing pipeline of new antibiotics," said Dr. Ed Septimus, a professor of internal medicine at Texas A&M Health Science Center and Medical Director for the Infection Prevention and Epidemiology Clinical Services Group at HCA Healthcare System. "It is a perfect storm in which, for some patients, it will feel like we are going back to the pre-antibiotic era."

What would it be like living in a world without antibiotics? You can say goodbye to many lifesaving procedures we now consider commonplace. Take heart transplants - they can be performed only because surgeons are confident the antibiotics they give patients before the procedure will prevent a postoperative infection. The same holds true for other complex surgeries. Chemotherapy severely inhibits the immune system, which is why chemo patients require antibiotics. "So many of these medical miracles that we take for granted are only possible because we have been able to deal with infectious complications," said Ruth Lynfield, the state epidemiologist and medical director at the Minnesota Department of Health. "If we can't do that, those areas of medicine - surgery, oncology, transplants, intensive care, neonatal care - could be lost."

And it could be even worse. Several medical experts noted that while a virus caused the influenza pandemic of 1918, most of the tens of millions of people who perished from the disease died of a bacterial infection in the lungs. With effective antibiotics, that complication can be treated. Given the scarcity of viral vaccines in much of the world, if a resistant bacteria takes hold, all anyone could do is find an effective way to dispose of the bodies.

Given the stakes, it is astonishing to realize the causes of this threat are well-understood and the ways to attack it well-known. Even as far back as 1945, Alexander Fleming, a pioneer in antibiotics, said, "the misuse of penicillin could be the propagation of mutant forms of bacteria that would resist the new miracle drug."

In essence, this crisis is looming because the world consumes too many antibiotics. In the United States, doctors prescribe them too often, many times because patients demand them for illnesses that are not bacterial and thus cannot be treated with antibiotics, such as colds and other sicknesses caused by viruses. The CDC found that the greatest use of antibiotics for humans occurs in the Southern states, a fact that medical experts struggle to explain. One thing the data and studies indicate, though, is that the areas with the highest use are most likely to experience the most resistant bacteria.

But the amount of antibiotics used by humans for medical purposes pales in comparison to the quantities fed to American livestock - pigs, chickens, cattle, and the like. According to the Food and Drug Administration, about 80 percent of all antibiotics sold in 2011 were used on animals, primarily for spurring growth.

What makes the use of antibiotics for growth in meat and poultry production particularly troublesome, experts say, is the low dosages. Using small amounts of antibiotics is more likely to create resistant bugs, the experts said, because the microbes are not wiped out. Instead, the bacteria are essentially trained to resist the drugs. "It creates a reservoir of drug-resistant genes," said Dr. Henry Chambers, a professor of medicine at University of California San Francisco.

Antibiotics are also used for animals in the United States as a prophylactic, to prevent infections likely to spread because of the meat and poultry production process. These so-called "production diseases" are the result of a system which places ever larger numbers of animals into ever smaller containment areas, exposing them to each others' feces, urine and - as a result - bacteria.

"We need to change the animal production system, where animals are healthier and infections become the exception and not the norm,'' said Price. "We should prevent infections in animals by not overcrowding them, not packing them in together and not exposing them to easy contamination."

The connection between antibiotic usage in animals and the development of resistant bacteria has long been recognized in Europe, which banned the use of the drugs as growth promoters in 2006. In the United States, the FDA only imposed voluntary restrictions in 2012, which, experts said, seems to have done little to decrease usage of antibiotics for livestock. "When you compare our use of antibiotics for animals to what they're seeing in Europe,'' said Lynfield, "we are not doing well."

Despite the magnitude of the risk, many basic strategies for containing and identifying threats have not been adopted. For example, there is no comprehensive international surveillance of threats from antibiotic resistance; identification only occurs with the appearance of an outbreak rather than through examination of strains.

According to the CDC, there is no systematic collection of detailed information about the use of antibiotics either in human health care or in agriculture in the United States. Without the ability to track, isolate and identify these pathogens, the both state and government health officials are unable to act until people start showing serious signs of illness or dying.

Medical experts agree that the use of antibiotics to spur growth in animals or to prevent disease caused by processing techniques has to stop. They also say that up to half of the usage of antibiotics by humans is unnecessary. Programs to engage in what is known as "antibiotic stewardship" - training physicians on the proper uses of the drugs and even limiting the ability of doctors in hospitals who are untrained in infectious diseases to prescribe antibiotics - have begun to be implemented, although they are not yet widespread.

Since large pharmaceutical companies have little economic incentive to develop antibiotics, the experts say, government has to step up, funding basic research into new treatments that would cut the cost for the development and sale of new drugs.

The hardest step could be restraining the international use of antibiotics. Many resistant strains are emerging in India and Southeast Asia, where antibiotics can be purchased without a prescription, according to Dr. Trevor Van Schooneveld, medical director of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. The resistant strains that emerge in those locations easily spread around the world; for instance, a resistant bacteria that causes urinary tract infections emerged not long ago in New Delhi; it is now being found in the United States.

The failure to pursue these solutions have left infectious-disease specialists frustrated as they see the world moving further and further away from the promise offered so many decades ago by antibiotics. Governments, they fear, may not act forcefully until the problem becomes overwhelming.

"We may have to wait until the deaths of some really prominent and previously healthy people,'' said Relman. "It might be that only by shocking the public will we be able to have the world get galvanized about this threat."