David Crane, a 63-year-old law professor at Syracuse University, sat in the sleek gray rectangular courtroom at The Hague and listened intently as the decision was delivered. This was the moment he'd been waiting on for a decade: the final verdict in the war-crimes trial of Charles Ghankay Taylor, the former president of Liberia.

On September 26, the court upheld Taylor's sentence of 50 years in prison for aiding and abetting war crimes and crimes against humanity that included murder, terrorism, rape, sexual slavery, and mutilations committed by rebel forces during Sierra Leone's civil war—a conflict that spanned 11 years and claimed some 70,000 lives. Taylor, who provided support to the Sierra Leonean rebel groups, is the first former head of state to be convicted of war crimes by an international criminal tribunal since the Nuremberg Trials. And Crane, who signed the original indictment in the case 10 years ago, and served as the chief prosecutor for the Special Court for Sierra Leone, was gratified by the court's decision to uphold the May verdict. "This is vindication and justice for the people for Sierra Leone," Crane told Newsweek in a telephone interview outside the courtroom in The Hague, just after Justice George Gelaga King of Sierra Leone had read the sentence. "It's a huge victory for justice [and] I'm very proud of the dozens of men and women who worked so hard over the past 10 years to see this day."

Crane served as prosecutor at the court from 2002 until 2005. During those years, the biggest psychological challenge was the absence of motive for the enormous brutality and violence. "We've all seen horrors in Rwanda and in the Balkans, but this was all of it—on steroids," he says.

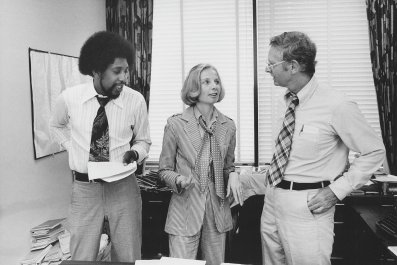

Crane, who was born in Santa Monica, California, studied West African politics and history at Ohio University before getting his law degree at Syracuse University where he would later teach. He served in the U.S. military and worked for the government for 30 years, overseeing various national-security organizations on behalf of the secretary of Defense and the intelligence committees of the U.S. Congress. But he had never been to the region when, one night in early September 2001, he received a phone call from the White House, telling him that he had been nominated for the position as special prosecutor.

At the time, Crane thought it was a joke. No one in the international community would support an American candidate for the position, he reasoned, given the Bush administration's adversarial stance toward the establishment of the International Criminal Court to begin with. But after six months of interviews, he received a phone call from then–U.N. secretary-general Kofi Annan's legal counsel, Hans Corell, telling him that he had been chosen for the job.

"There were a lot of people within the United Nations who didn't want me there," says Crane. When he took on Taylor, "against the wishes of the U.S.," because the law and the facts required him to, "they came to realize that I was a true international prosecutor and not some type of American lackey working for George [W.] Bush."

Taylor himself called Crane a "redneck racist" and said he was only going after him because Taylor is black. (The two never met until 2008 when Crane attended one of Taylor's hearings in The Hague.) And some of Crane's former colleagues at the court criticized the American for what they saw as a "missionary attitude."

Still, no one disputes that Crane's greatest achievement was to help secure the arrest of Taylor, who was in exile in Nigeria until 2006. He and his team, he says, "were driven by a righteous fury."

Crane now lives a quiet life with his wife in the Smoky Mountains in Waynesville, North Carolina, and lectures on international criminal law at Syracuse, flying to work every week. But the former prosecutor still has a strong commitment to international justice. He is working on a book about his experiences at the special court, titled Strike Terror No More after a biblical psalm. He is also working with a team of lawyers and civil-society advocates to set up an archive of war crimes and atrocities committed in Syria that could be used as a basis for prosecution. "We former chief prosecutors are like racehorses," he says. "You can put us out to pasture but we still want to run."