The future home of the Central Reference Laboratory, a $102 million state-of-the-art center to secure biological agents that could be used as weapons of mass destruction, is located in the former Soviet Republic of Kazakhstan. A visitor making the trip from nearby Almaty, a picturesque city flanked by snow-peaked mountains, to the imposing four-story, concrete-and-steel structure where the center will be housed might be put in mind of a James Bond movie and dimly imagine that, behind these walls, evil genius Ernst Stavro Blofeld plots SPECTRE's world domination while stroking his cat.

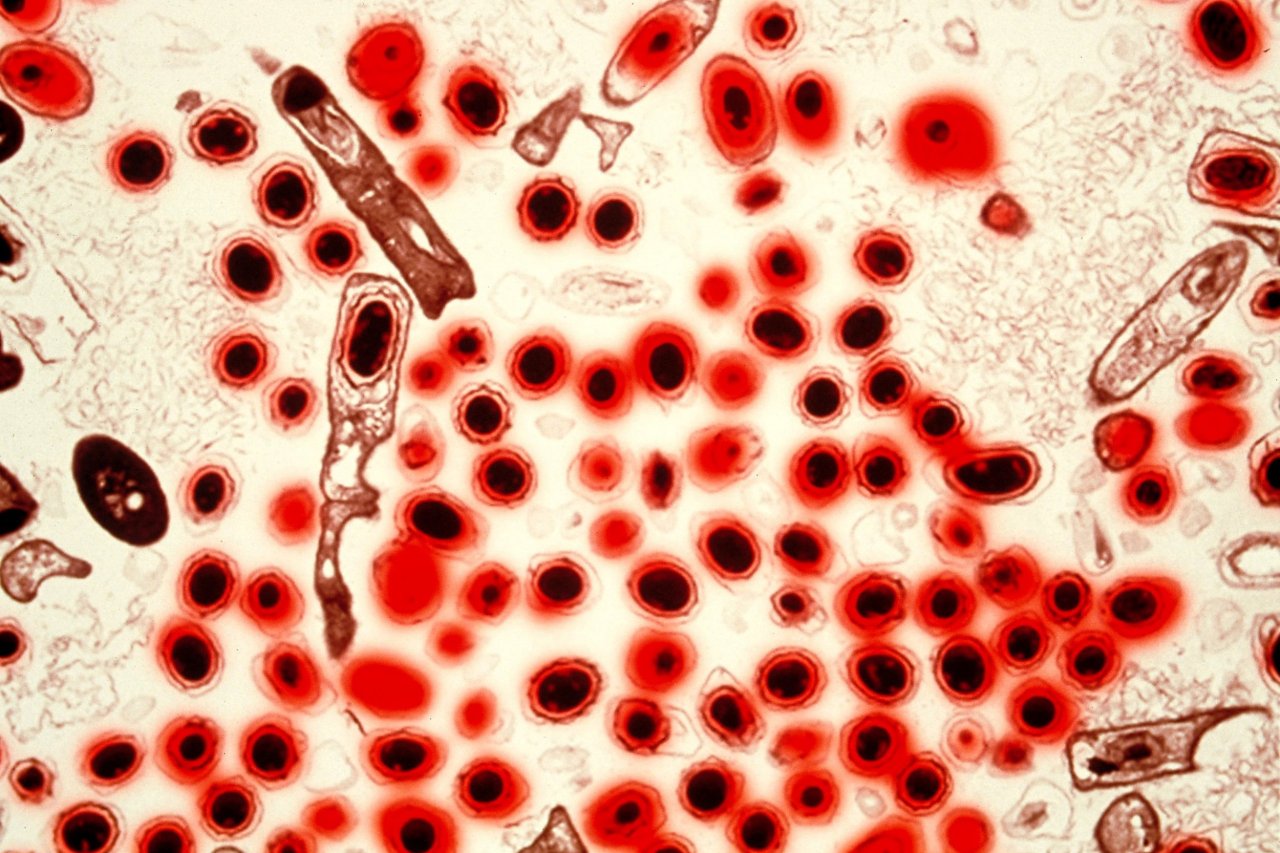

The reality is no less fascinating. Funded by the U.S. military's Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the laboratory will serve a dual purpose: to research dangerous pathogens such as anthrax, tularemia, and the plague, and to keep those same pathogens secure—in other words, to act as a line of defense against global pandemics.

"These pathogens don't know borders," Charles Carlton, a 42-year-old American lieutenant colonel tells Newsweek. Carlton, a military representative at the U.S. Embassy in Astana, the capital, serves as the liaison between the U.S. and Kazakhstan on construction of the laboratory, due to open in 2015.

A member of the Special Forces and a specialist on the former Soviet Union, Carlton is used to living in unusual locations. He grew up an army brat and lived in Belgium and Panama as a child; he then enrolled in the military himself and did tours in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

Serving as a young captain in command of a Special Forces detachment in Kosovo prepared him for his current job, he says. "I quickly learned that a lot of the decisions that I had to make on the spot had to be within the overall larger strategy of what we were trying to accomplish"—but there wasn't anybody to tell him exactly how to do it, a feeling that he described as "very liberating." "Being here," he says, "is very analogous to those days as a captain—just probably on a larger level."

When asked why the U.S. should spend money on a research lab in such a remote corner of the world, Carlton said, "There's no such thing as a Kazakhstani pathogen. This is a worldwide threat, and it's important to the U.S. because, by controlling these especially dangerous pathogens and these threats to animals and humans, we prevent enormous costs down the road."

Call it the "better safe than sorry" approach to national security. "I would not want to overly concern the U.S. population," Carlton says, "but it's of serious concern [and] we feel it's necessary to take these proactive steps ... so that if something does come out, we have a readily identifiable repository that we can use to help to detect and diagnose" the disease.

During the Soviet era, Kazakhstan was "kind of a theme park of Soviet WMD," says David E. Hoffman, author of the book The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the ensuing security vacuum in places like Kazakhstan, it became imperative for the West to try to secure any weapons of mass destruction in danger of falling into the wrong hands. While the most imminent threat was nuclear, both in terms of leftover strategic weapons and materials like plutonium and highly enriched uranium, Kazakhstan had also been home to a vast biological-weapons program. "The Soviet Union built the largest biological-weapons program known to mankind," Hoffman says. "They did some monkeying around with genetics to try to create new diseases and they also harvested the pathogens they found in nature to [turn them into] weapons." Because of this history, Kazakhstan has been an advocate of nonproliferation since the 1990s.

Labs like the one being built in Kazakhstan and an existing facility in the country of Georgia are important because they function as "early warning systems or sentinels against pandemic disease," so that "pathogens can be identified quickly before they travel across the oceans," says Hoffman. "They can be kind of a beacon, or a warning [system], against diseases that could just as easily affect Manhattan or Malibu. Diseases don't stop at passport control."

Rob Verger reported from Kazakhstan on a fellowship from the International Reporting Project.