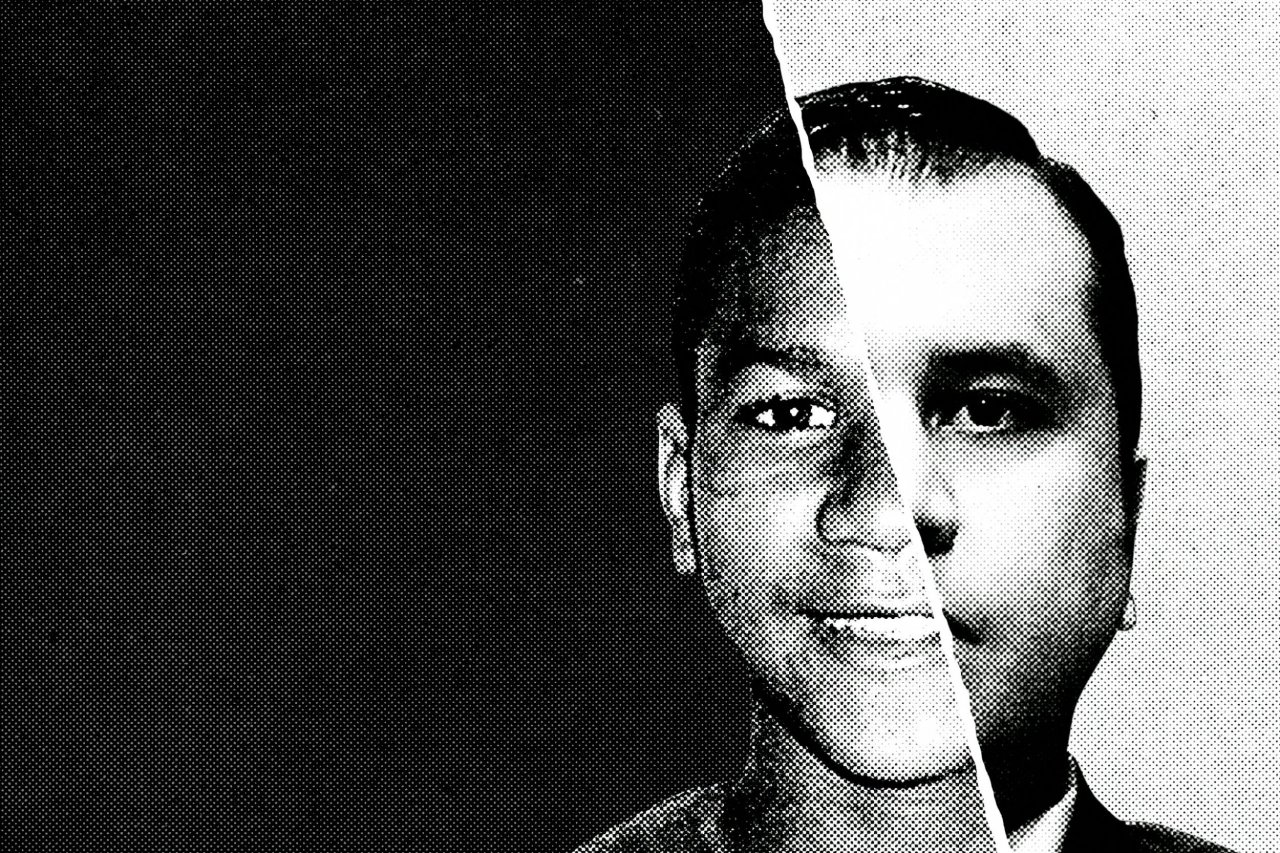

By this point, all Americans know the facts. A teenager, Trayvon Martin, was pursued and killed. The shooter, George Zimmerman, was acquitted, his claim of self-defense validated by a jury. We have lined up to state our views about what should happen next: vocal protesters and advocates (I count myself among them) think that the system failed at critical points and should be corrected, from the "stand your ground" law that empowered Zimmerman to the investigation and prosecution of the case itself. Others are assembling to protect gun rights and the right to self-defense.

In service of these goals, we will march. We will tweet. The Justice Department will investigate, talk radio will opine, and some laws and policies will hopefully, needfully, be changed.

But when it is all over—when the political debates have run their course, when the pundits have moved on—we will still be left with something else. Something harder to describe. A set of noxious gut feelings about Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman—and where we all stand on the issue of race.

For black Americans, it will be that sour, aching feeling that someone, in the dark of night—empowered by a weapon, a reason, and relative impunity—can gun us, or our sons, or our husbands, down. It's that thing my fiancée felt when she looked at me after we watched the verdict, hands held, sitting on the floor of my office. This is an intelligent woman, law-school educated, not overly emotional, and never at a loss for words; but channeling Trayvon's mother, with a stunned look in her eyes, all she could muster was, "Can they really just kill our kids?"

For many white Americans, it will be a different though related sentiment that will linger. It's a sentiment that is largely quiet on television and social media—because it would be swiftly condemned—but we must acknowledge that it's there, that it's represented in massive numbers across the country, in opinion polls, congressional districts, and, yes, on juries.

It's a view that has sympathy for the Martin family, but at the end of the day also has sympathy for George Zimmerman: You know, sue me, but a tall, hooded black man that I've never seen before in my neighborhood is maybe a little frightening. And I don't know what happened next between Zimmerman and Trayvon. But if, God forbid, I, or my husband, or my wife, is ever in that situation, I might like the right to ... Most would shudder to finish the sentence.

When the verdict came, all my fiancée could muster was, 'Can they really just kill our kids?'

Our marches will proceed, and they should. Our laws will be debated, and hopefully changed. A civil case, and a federal case, will at least be considered. But when it's all said and done, in the pits of our stomachs, we are still left with this ... thing. Two new versions of a very old fear—with a wide chasm in between.

What to do about it? In the days after the Zimmerman verdict, I approached several people who have spent lifetimes building bridges and breaking down walls. I asked them what on earth black and white Americans could do to seek and find justice in our country and heal ourselves in the process.

ONE WOULDN'T necessarily think of the Southern Baptist Convention as a place to look for advice on race. The convention was formed in 1845 when its members, insisting that foreign missionaries should be able to own slaves, split from their Northern Baptist counterparts. After that time, for more than a century, the leadership of the SBC was at the forefront of restricting minority rights. Southern Baptists were found among the Klansmen and lynch mobs during Reconstruction. They fought for the passage and maintenance of Jim Crow laws. And the convention—our nation's largest Protestant denomination—was one of the chief opponents of the civil rights movement and Dr. Martin Luther King.

That consistently tragic history is what makes a guy like Russell Moore so remarkable. A white Southerner with a broad smile, jet-black hair, and a ceaselessly cheery demeanor, Moore is the new head of the Southern Baptist Convention's Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, the public-policy arm for the denomination, and its most powerful spokesperson. And, believe it or not, he has emerged as one of our country's most articulate and persuasive leaders on the issue of race outside of the traditional civil rights community.

It started when he was a very young child attending Sunday school in Biloxi, Mississippi, which is just off the Gulf of Mexico and about as far south as you can get. Moore was playing with a dirty quarter and placed it in his mouth, as boys are prone to do. Noticing the infraction, his teacher scolded, "Russell, take that quarter out of your mouth. You never know if a colored man touched it!" Little Russell sat, stunned, as the teacher proceeded to lead the class in the famous song "Jesus loves the little children; all the children of the world ..."

The experience was jarring for Moore. He told me that even at a young age, he knew those two things—racism and the Gospel—could not comfortably rest side by side. "I see now that my teacher was dealing with a sort of ethical schizophrenia," he says. She held one belief about God the Father, and quite another about his African-American children.

Since his early Mississippi days, Moore has made it a personal goal to understand the manifestations of racism in the American soul and root it out—first as a congressional aide, then as a professor and dean at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He began his tenure as the Southern Baptist Convention's chief ethicist with a call to racial reconciliation before thousands of Southern Baptists.

Black and white Americans are having two entirely different conversations.

Through his work, Moore told me that he learned that people like his childhood Sunday-school teacher are usually not "evil white supremacists plotting in a lair somewhere trying to harm people, or infect the rest of the country with their ideology." Rather, issues of racism are pervasive among otherwise well-meaning folks; these matters are, as he puts it, "a part of our ambient culture."

When it comes to the case of George Zimmerman and Trayvon Martin, and the racial questions that have arisen in its aftermath, Moore told me that the core problem is that black and white Americans are having two entirely different conversations.

"African-Americans tend to speak about the case in broad social and political terms," he explains, "but we rarely get to hear their own quiet, personal stories. The real message of the Martin case didn't hit me until an African-American pastor, a friend of mine, told me that there are some places he doesn't want his young son to go, because he's 'afraid of him becoming another Trayvon.' "

"This man was fearful for his son's personal safety," Moore continues. "That hits home for me, as a father and as a man. And it's the type of personal story that can shatter the myth that everything is OK."

Conversely, Moore suggests that whites move away from the micro and toward the macro when they consider the Zimmerman verdict: "On the other hand, too many white Americans deal in particulars, without realizing that it's larger than that," Moore says. "It's not just about this individual case; it's about the fabric of American history. We have to recognize that African-Americans see Trayvon Martin's face alongside Medgar Evers, Emmett Till, and others that most people will never know. We have to acknowledge that in our conversations."

To Moore, where and how this dialogue happens matters. "These conversations have to be had at the local level, organically, and it can't be in the heat of nationally polarized moments. We have to take time to invest in preparation. There's advance work that has to be done."

"It's like marriage," Moore adds. "You have to work on issues in advance, when times are good—not when you're screaming at each other and on the way out the door."

CONGRESSMAN JOHN Lewis, who marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, with billy clubs crashing down upon him, has seen racial conflicts wax and wane. But for him, the Zimmerman trial was still in a class by itself. "When I heard the decision, I fell ill," he told me. "I couldn't speak about it for a day."

He has since done a lot of thinking about the trial and where the country should go from here. I asked him what the best way forward was, expecting to hear that people should organize and that policies should be changed. He did make these points, but then paused for a second. "You know, here is the key: to be made whole, we have to forgive George Zimmerman," Lewis said. "We have to forgive those who believe that what he did was right."

African-Americans see Trayvon Martin's face alongside Medgar Evers, Emmett Till, and others.'

"I forgave and never had ill will towards George Wallace, or the people who beat me in Rock Hill, South Carolina, in 1961," he continued. "In order to be effective, all of our actions, all of our organizing, all of our conversations have to flow from a consistent ethic of forgiveness."

Lewis said that he learned this lesson from a man named Jim Lawson, a black Methodist pastor and missionary from Ohio who had spent time in India studying the principles of Gandhi. Hearing about Lawson, Martin Luther King Jr. recruited him to journey south, saying, "Come now. We don't have anyone like you down here."

"Jim Lawson taught me that any meaningful action on the topic of race must begin with forgiveness," Lewis says. "Once we forgive, we can encourage the majority population to walk in our shoes—the shoes of a black mother, a black father, a black son, a black daughter. But first, we have to forgive."

THE PRESCRIPTIONS of both Lewis and Moore suggest just how much we need to do differently as a country—and they are right to focus on the challenges ahead. But Maya Angelou offered a different perspective when we spoke: she focused on how much we are already doing right. Angelou—who has knit a fair piece of our country's cultural fabric together over the years with her words, poems, and life—made clear that her heart was broken for Trayvon Martin. Yet—and I did not expect this—it also brimmed with hope.

"Look at the people who are protesting!" she told me. "Look at the people who are standing up for their rights." In their faces she saw a glimpse of the American future. "These aren't just black people or white people—these are right people," she said. "These crowds, some of them are 50, 60 percent white." Angelou compared it with the days of marching with King, when Christians, Muslims, and Jews stood side by side, and Northern students joined Southern sharecroppers to demand ever-greater liberty.

For Angelou, this is the key: the fact that an increasing percentage of white Americans now deeply identify with the struggles of black folks. In the wake of Trayvon's death, "it is not just African-Americans who feel belittled and injured," she told me. "No, the desire to understand what happened, to comprehend, to inform, to ingest what we know to be right has finally spread to people of all different backgrounds and beliefs."

PERHAPS IT will continue to spread. I certainly hope it does. But first, we have to be honest with ourselves—about our hopes, as Maya Angelou expresses, but also about our fears.

Some have called for a "national conversation on race," maybe another speech by President Obama on the subject, like the one he delivered years ago in Philadelphia, or an expansion of his more recent remarks on Trayvon Martin. While I believe these types of conversations and speeches are helpful—the president's invocation that, if he had a son, "he'd look like Trayvon" had a healing effect for many—I wonder if something at once greater, and smaller, is needed.

Instead of a national conversation on race, perhaps it's time for a million local ones. Over coffee or dinner, I'd love to listen—really listen—as my neighbors tell me how they feel when they see young men like Trayvon Martin, in the dark of night, hooded sweatshirts and all. I'd like to then share a bit of what I know about these boys, who are so much like me: their history, their families, their angst, their dreams.

I don't know what would result from that type of dialogue; previous national moments to finally speak candidly about race have fallen by the wayside. But maybe it's time to lay bare our thousands of anxieties about George Zimmerman and Trayvon Martin, and see where it gets us. In doing so, perhaps we'll learn more about this thing called race, and begin to address our gnawing fears.