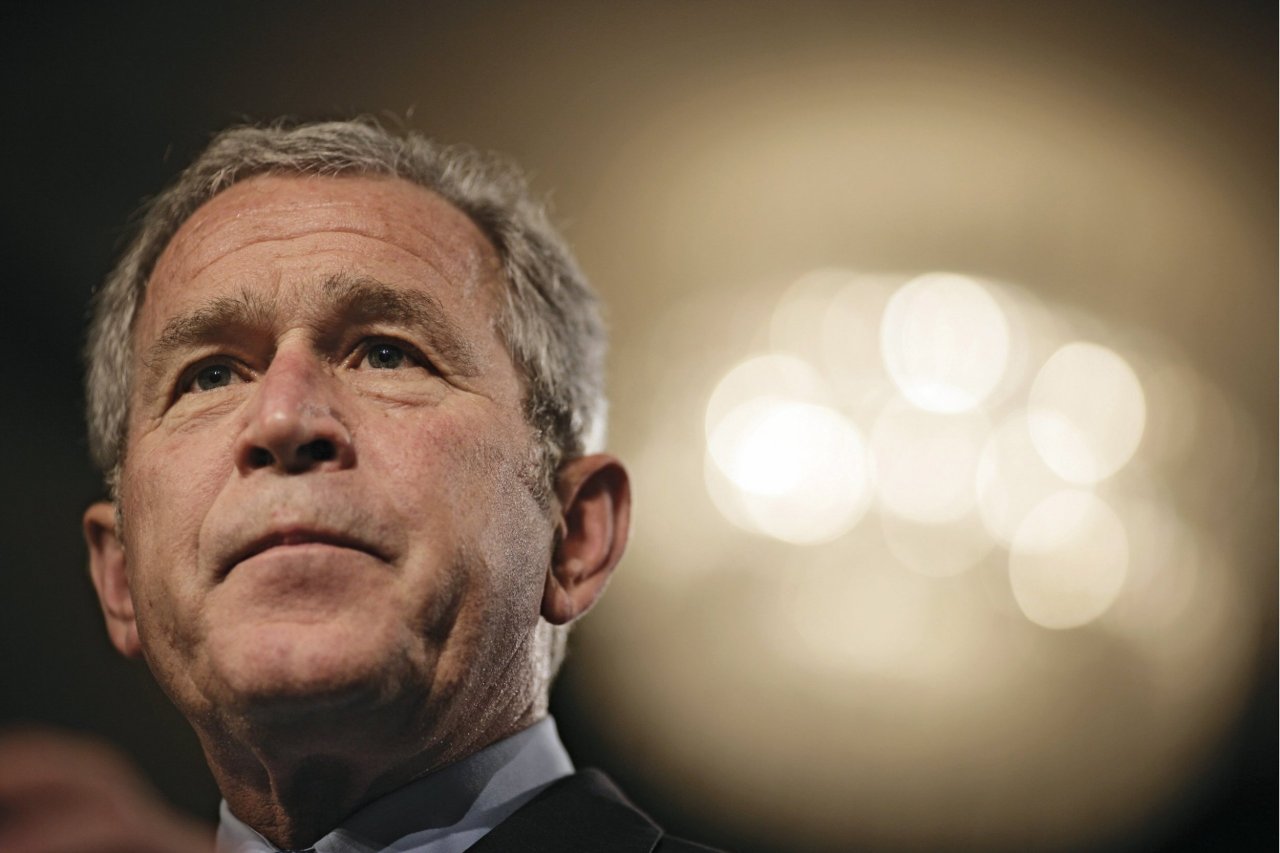

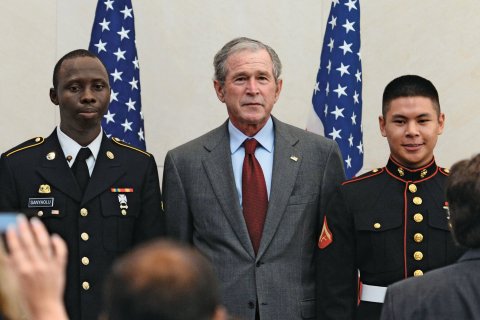

The juxtaposition between image and text could not have been more humiliating. The photo above The New York Times story featured a craggy-faced George W. Bush—now looking like a cross between himself and his father—alongside newly minted American citizens from Nigeria and the Philippines. Below it read the story's headline: "Republicans in House Resist Overhaul for Immigration." Or as the New York Daily News might have phrased it: "GOP to Bush: Drop Dead."

It's becoming a pattern. As early as 1994—when as the newly elected governor of Texas he berated his California counterpart, Pete Wilson, at a Republican governors meeting for demonizing Hispanics—Bush made being pro-immigrant and pro-Hispanic a centerpiece of his political identity. But last week, despite warnings from his old consigliere, Karl Rove, the congressional GOP buried legislation offering illegal immigrants a path to citizenship.

A few days earlier, conservative heavyweights—from Fox's Bill O'Reilly to The New York Times's David Brooks to The Wall Street Journal's editorial page—defended the military's coup in Egypt, thus rejecting Bush's doctrine of Middle Eastern democracy promotion. And if that wasn't enough, House Republicans on July 11 stripped food stamps from the farm bill for the first time since 1973—sharply breaking from the "compassionate conservatism" that had led Bush to back higher government spending on education and prescription drugs.

The party Bush once commanded is repudiating much of his legacy. And it's doing so because it no longer shares his temperament. Bush was, at his core, an optimist. For starters, he was an optimist about the budget. He had taken over in the wake of a late-1990s economic boom that erased the deficits built up during the Reagan years. For Bush, the message was that you can cut taxes, maintain popular domestic programs, and dramatically boost military spending without worry, because economic growth will eventually balance the budget, as it did in the 1990s. As Dick Cheney famously replied when then–Treasury secretary Paul O'Neill warned that Bush's economic policies were leading the country toward a fiscal abyss, "Reagan proved that deficits don't matter."

Bush was a cultural optimist, too. He had taken power on the heels of what Samuel Huntington called the "third wave" of democratization, a mighty tide that began when Spain and Portugal shrugged off their autocratic governments in the mid-1970s, and extended in the 1980s and 1990s from South Korea and the Philippines to Argentina and Chile to Hungary and Poland to South Africa. This historic shift—which made democracy the normative form of government not merely in Northern Europe and North America but throughout the world—shaped "neoconservative" intellectuals like William Kristol, Paul Wolfowitz, and Robert Kagan. But it also dovetailed with something personal in Bush. As his former speechwriter Michael Gerson has noted, Bush's brand of Christianity was strikingly untroubled by original sin. His own life was a tale of purposeless, self-destructive wandering followed by radical transformation via the power of faith. And while other conservatives focused on an entrenched "culture of poverty" that made it difficult to change the lives of America's urban poor, Bush championed the idea that with religious counseling, inmates in Texas jails could experience the same radical, redemptive change he'd seen in his own life.

Bush, in other words, was an optimist even when it came to cultures—like the ones prevailing in America's inner cities or in the Arab world—for which other conservatives held out little hope. Despite the incredulity of many on the right, he responded to 9/11 by insisting that Muslims were just as desirous of democracy, liberty, and peace as Christians and Jews. And he set about proving that in Iraq. "The human heart," he told the American Enterprise Institute two months before the invasion, "desires the same good things, everywhere on earth." That universalism also shaped his views on immigration. If Iraqis shared the same basic values as Americans, so did undocumented Mexican immigrants.

The party Bush once commanded is repudiating much of his legacy. And it's doing so because it no longer shares his temperament.

Even during Bush's presidency, his economic and cultural optimism met resistance inside the GOP. From the moment 9/11 hit, polls found that many conservatives—contra Bush—did consider Islam a violent religion. In 2003 the White House and GOP leaders had to brutally pressure some congressional Republicans to make them back Bush's expansion of Medicare. And in 2007 Bush's push for comprehensive immigration reform failed in large part because of lack of conservative support.

But since Bush left office, the GOP pessimists have taken full control of the party. When Bush was jacking up the deficit via tax cuts and defense spending, the conservatives who worried about America's fiscal health mostly held their tongues. When Barack Obama replaced him, however, and began spending money on a domestic stimulus package and a universal-health-care law, the deficit became a GOP obsession. Gone was Bush's happy talk about how economic growth, which had overcome the Reagan deficits, would do so again. In its place came a dystopian vision of America as Greece: its currency worthless and its coffers empty. The GOP, the party that under Bush said America could have it all, under Obama has become the party that says America can't even afford food stamps.

If the post-Bush GOP is more pessimistic about America's fiscal health, it's also more culturally pessimistic—both at home and abroad. Under Bush, when the GOP won a higher percentage of Hispanic votes, Republicans liked to say that new immigrants embodied the values that conservatives revered: religious faith, family unity, self-reliance. But in the post-Bush era, as Hispanics have fled the GOP, a nastier stereotype has taken hold: Hispanics are part of the 47 percent "who are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them," in Mitt Romney's immortal words. As O'Reilly put it on election night, "You are going to see a tremendous Hispanic vote for President Obama," because Hispanics and other Democratic voters "feel that they are entitled to things."

To some degree, the intra-Republican conflict over immigration has been a contest between these optimistic and pessimistic narratives. After Romney's defeat, hordes of conservative bigwigs promised, Bush style, that if the GOP embraced a path to citizenship for immigrants, Hispanics would reveal themselves to be a "natural Republican constituency" (in Charles Krauthammer's words). But when comprehensive immigration reform reached the House of Representatives, Republican members of Congress rejected that logic, partly because they don't need to win Hispanics to keep their seats and partly because they don't think the GOP can win anyway.

If the GOP has rejected Bush's optimism about Hispanics, it has rejected his optimism about Arabs, too. For conservatives who never believed Bush's universalistic rhetoric, Iraq's refusal to become the pro-American liberal democracy he promised made it easier to insist that Arabs and Muslims didn't share our values after all. And once Bush left office, top Republicans were liberated to become more crudely anti-Muslim. In 2010 key figures in the party denounced the construction of the Ground Zero mosque, and during the 2012 elections, GOP presidential contenders pandered to voters worried about the imposition of Sharia. When it became clear that the Arab Spring would empower the Muslim Brotherhood, only a few conservative intellectuals held to the Bush line that the United States should support democratic elections even if they don't deliver the results we want. More common were denunciations of President Obama for acquiescing to a fanatically anti-American revolution in Egypt in the same way Jimmy Carter had in Iran. When the military overthrew the Brotherhood earlier this month, leading conservatives breathed an audible sigh of relief.

For conservatives to be at least somewhat pessimistic about the future isn't surprising. After all, conservatives want to conserve. But America's most politically successful conservative presidents—like Ronald Reagan and, to a lesser degree, Bush—have conveyed optimism by promising that under their leadership, the America of the future would reclaim the best values of its past. The problem for Republicans today is that it's hard to argue that with a straight face. At this moment, at least, there's not much evidence that a more heavily immigrant, more heavily nonwhite America will bring back the values of the 1950s, or that democracy in the Arab world will boost American power, or that future economic growth will restore the fiscal solvency of yesteryear. It's hard for conservatives to be optimistic because George W. Bush's optimistic predictions—about the budget, the transformation of the Middle East, and Republican success with Hispanics—have not come true. If George W. Bush himself were a post-Bush Republican, he might be pessimistic, too.