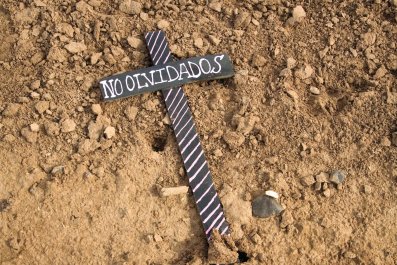

NEGOTIATING A peaceful solution to the nearly 13-year-old Afghan conflict has never looked more complicated. The Taliban's leadership is so deeply divided over the crucial question of whether to negotiate with its enemies—the U.S. and President Hamid Karzai's government—that the insurgency could splinter, with one faction negotiating a separate peace with Washington and Kabul, while the other, supported by hard-pressed fighters in the field, opts for protracted war.

And just when there seemed to be some positive movement last month, Karzai loudly demonstrated that he has serious reservations about the peace process too.

Ironically, the fear of a debilitating internal rift has pushed the insurgency's senior leadership to give peace talks a chance. In late May the insurgency's ruling military and political council, known as the Quetta Shura, called an emergency meeting in reaction to another just a few miles away between dissident senior Taliban ministers, governors, and commanders. The shura, led by powerful commander Akhtar Mohammad Mansoor, feared that the Taliban's former finance minister, Agha Jan Motasim, an outspoken peace advocate who led the parallel meeting, would win agreement from his supporters to abandon the fight and join the Karzai regime.

To prevent this, Mansoor reluctantly decided to adopt Motasim's pragmatic policy and flashed the green light to the Taliban delegation, which had been marking time since early last year to open a political office in Doha, Qatar, and begin a dialogue with not only the Americans, but also an Afghan-government delegation.

The news that the Taliban's office in Doha was open for business seemed to be a real breakthrough. "To avoid a serious internal split, Mansoor decided to drink the glass of poison and agree to talks that the Taliban had always vowed would never happen as long as there were foreign troops in Afghanistan," an Afghan provincial governor, who is close to Karzai, tells Newsweek.

Regrettably, the Taliban badly overplayed its hand by presenting its Doha office as a diplomatic mission rather than as simply a venue for talks. Feeling double-crossed by both the U.S. and the Taliban, Karzai exploded, suspended security talks with Washington, and canceled a scheduled trip to Doha by members of his negotiating delegation. And as a result, the Taliban's Doha office is now closed.

European diplomats in Kabul were stunned by the president's histrionic outburst. "Kabul is always saying, 'We are secretly talking to the Taliban,' but when the Taliban come up with a positive gesture, Karzai seems to jump back," says one European envoy in Kabul. "We have told the president that the peace process is a key part of the West's strategy. We hope we won't lose this opportunity."

To further complicate the search for peace, many insurgent fighters in the field are adamantly against talking to their enemies. "This notion of suddenly talking to Karzai angers fighters on the ground," says a senior Taliban political operative known as Zabihullah. "Unfortunately our leadership has trouble explaining to the fighters why, after 12 years of suffering, it is now time to talk to Karzai."

Or as a British diplomat puts it: "Fighters in the field are the key. If they are not convinced that negotiations are the way to go, then peace could be a far-off dream."