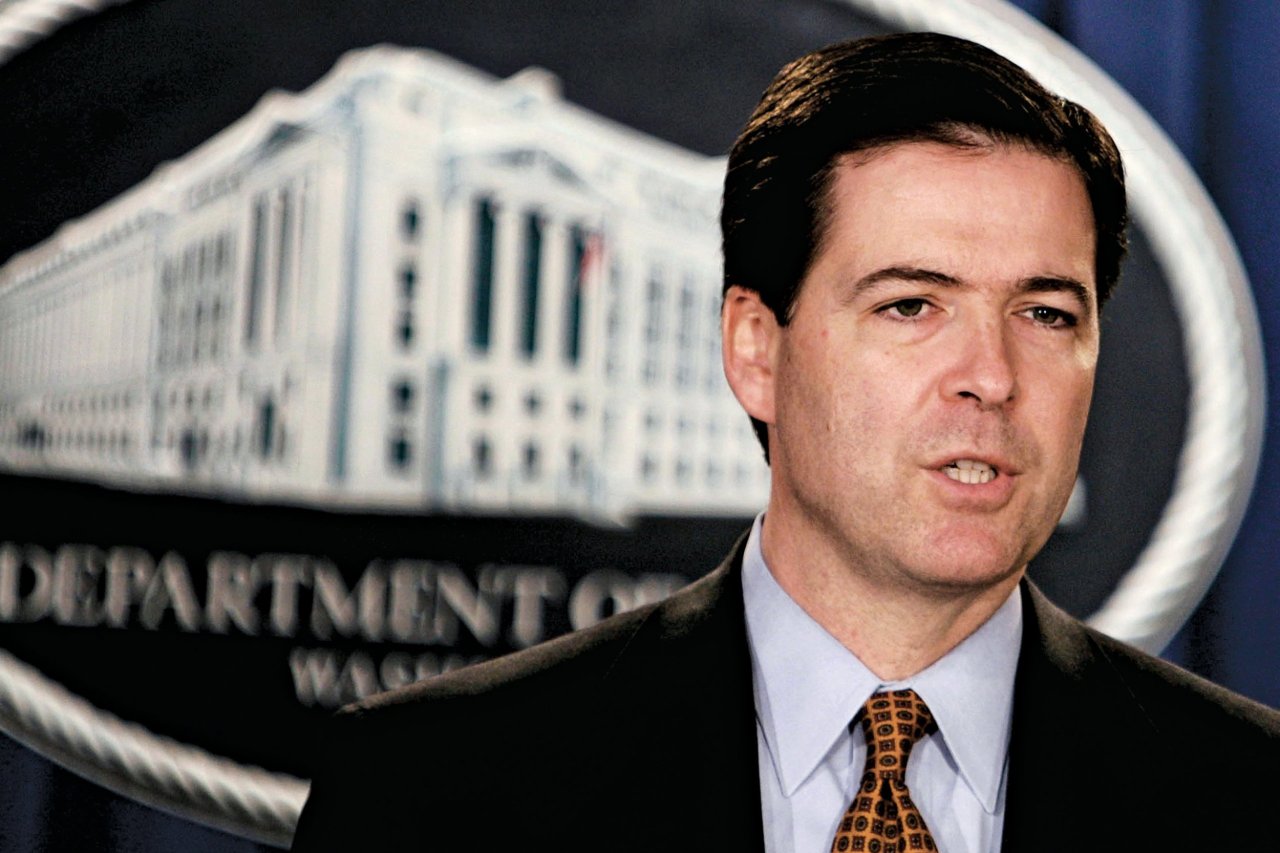

JAMES COMEY, President Obama's expected choice to lead the FBI, will likely be nominated amid the uproar over the National Security Agency's domestic surveillance programs. But Comey, a former deputy attorney general and veteran prosecutor, is thought to have a powerful shield of protection against fallout from the spying controversy. If the public knows anything about him, after all, it's his role in leading the internal Justice Department rebellion against the Bush administration's warrantless wiretapping program. It was this episode that led to the iconic hospital-room scene in which Comey thwarted senior White House advisers who were attempting to pressure an ailing Attorney General John Ashcroft into reauthorizing a surveillance program the Justice Department had deemed illegal.

And yet nearly a decade later, the specific aspect of the broad program Comey and his colleagues objected to remains poorly understood. In 2008 I reported in Newsweek that the insurrection was over the vast and indiscriminate collection of metadata, possibly relating to phone calls and emails. The NSA was collecting and storing the telephone numbers of virtually all Americans, as well as the times and duration of the calls. In addition, the government was vacuuming up and storing the subject lines of emails, the times they were sent, and the addresses of both senders and recipients.

Now, in the wake of revelations about the Obama administration's continuation of the surveillance programs, a clearer picture of the reasons for the rebellion is beginning to emerge. Knowledgeable sources say it was about data relating to email and other forms of Internet communications—but not telephone metadata.

Over the weekend The Washington Post reported that the NSA had been "siphoning off" email metadata and technical records of Skype calls from providers that included AT&T, Sprint, and MCI (which later merged with Verizon). It was this kind of Internet-based surveillance that Comey objected to. By contrast, he was satisfied that the collection of phone metadata was legal. In fact, a former senior intelligence official tells me, Comey signed orders authorizing the sweeping up of call data on multiple occasions, even after the March 2004 rebellion. "The phone program was never in contention," says the source.

Ultimately the Internet-collection program was modified, satisfying Comey and his fellow rebels that it met the requirements of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act and therefore was legal. The legal distinction between the telephone program and the Internet program remains unclear. But it now appears to be a safe bet that one of the most dramatic showdowns of the Bush administration turned on highly technical aspects of digital communications and mind-numbingly complicated provisions of surveillance law.

The last time Comey testified on Capitol Hill, he gave a riveting account of the hospital scene and his fight to vindicate the rule of law. If he gets a chance to testify in a Senate confirmation hearing, he might end up having to explain why it was OK to vacuum up the telephone records of virtually all Americans, but not their Internet data. Of course, it will probably take place in a closed session.