It's a story as old as justice. The crazy man crying out, "It's not fair!"—his calls falling deaf ears.

Now it's Phil Spector's story too, about to be twice-told anew, once in his last-chance appeal being considered by a federal court and again by David Mamet in a new film to air later this month. Both argue that whatever happened to cause the bloody and gaudy 2003 death of actress Lana Clarkson—at Spector's home, a gun owned by the legendary music producer discharged in her mouth—Spector should not have been convicted. Innocence is not the question. The right to a fair trial is.

It's a story I also have told. A month before the start of his first trial—which ended in a hung jury—I started making a documentary film with Spector, as complicated and self-destructive a man as you can imagine. He'd been a celebrity for almost 50 years, since writing and performing his first No. 1 hit song "To Know Him Is To Love Him" at 18 years old and going on to develop his hallmark Wall of Sound. As a producer, he had dominated the '60s charts, later producing Let It Be (the final Beatles album), George Harrison's and John Lennon's first solo albums, and the most successful Ramones record. In all that time, he never let a filmmaker near him—until the eve of his first trial. The result was my feature-length documentary The Agony and the Ecstasy of Phil Spector, which intercut no-holds-barred conversations between Spector and me in his castle with the trial footage from the courtroom.

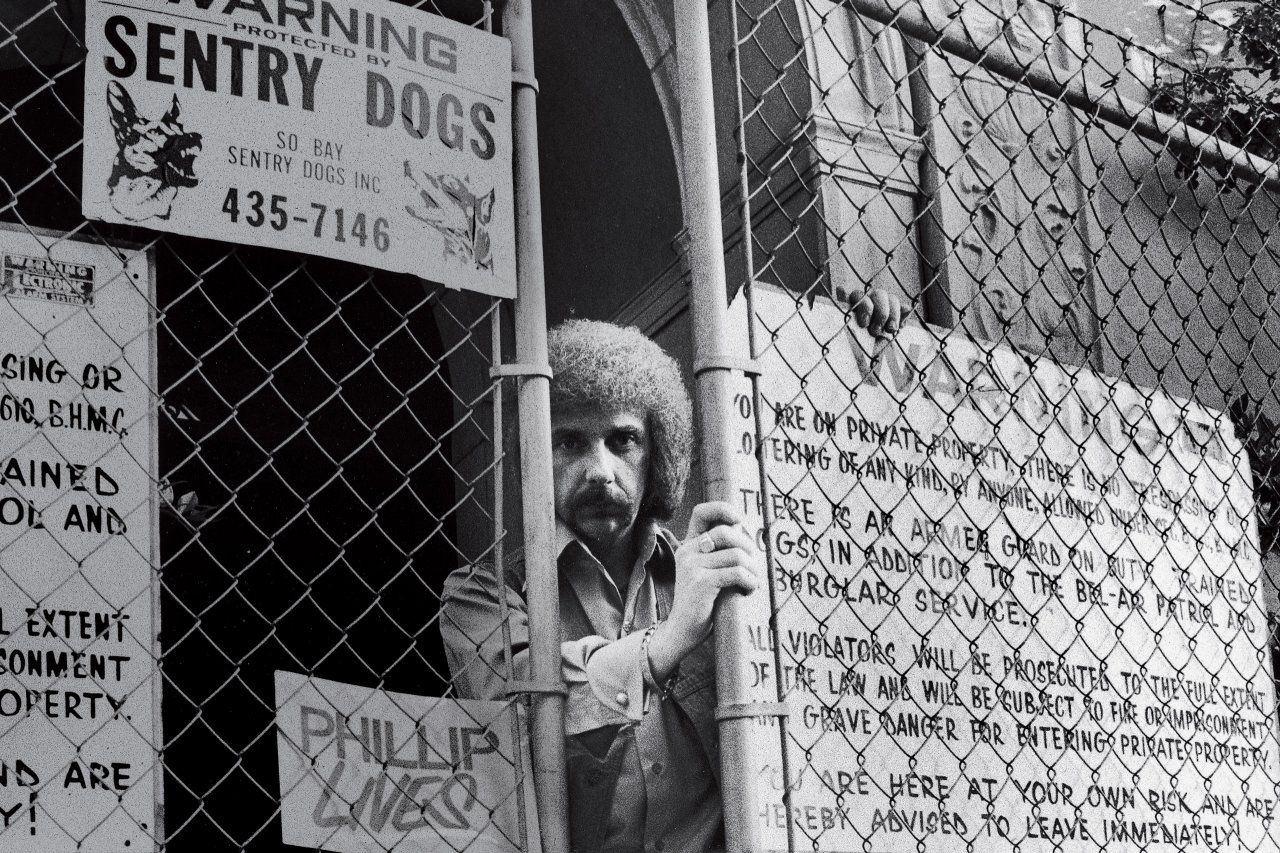

There were many surprises along the way, the first being that Spector's castle, where Clarkson died, was in blue-collar Alhambra on the outskirts of L.A. and not in Beverly Hills or Malibu. As Spector told me, when he decided to leave his Beverly Hills mansion, he wanted to live in a castle. His real-estate agent found two for sale and the one in Alhambra, atop the town's only hill, took his fancy.

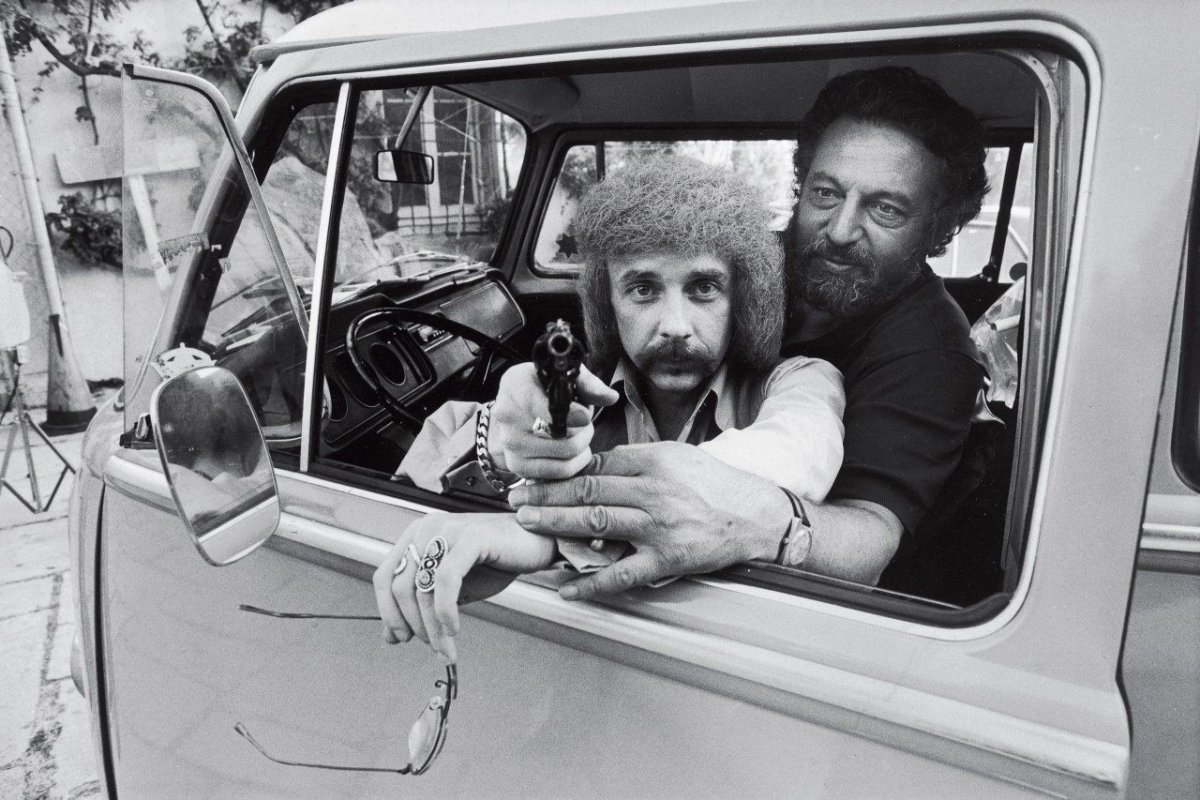

But if Alhambra was a surprise, the possibility that he'd finally shot and killed somebody was most definitely not. After all, the world had been hearing stories about his gunplay and mean temper for more than 30 years. He'd even been reported to have taken a shot just past John Lennon's head after they'd made the Rock & Roll album together, to encourage Lennon to hand over the acetate master recordings. He's said to have pulled a gun on the Ramones, and on Leonard Cohen—who became even more of a hero to me when he told my journalist friend Chris Goodwin that he'd responded by saying something along the lines of, "Oh, Phil, you've been pulling guns on everyone your whole life and you've never shot anyone yet and you're not going to shoot me either, so just put it down." And Spector was so taken aback that he did.

Ringo Starr had been Spector's neighbor, separated by a fence and a small road in Beverly Hills. A couple of years ago we got to talking. "The problem with being a fookin' gun nut is that sooner or later somebody gets shot," Ringo said to me. "But you can't take away his music." Spector had given his generation its soundtrack.

And that's the paradox of Phil Spector. Yes, he was the musical revolutionary who transformed rock and roll into art, invented the very idea of the modern record producer. On the other hand, he was notorious as the monster who kept his wife, Ronnie Spector, locked up in their home, cheated his artists out of their royalties, threatened countless people with his countless guns, and lived as a paranoid recluse surrounded by bodyguards.

And then a former starlet, washed up at 40, died in his lobby from a gunshot fired deep inside her mouth. A perfect climactic chapter for Hollywood Babylon, a scene scripted for a tiny wig-wearing nutter in five-inch Cuban heels.

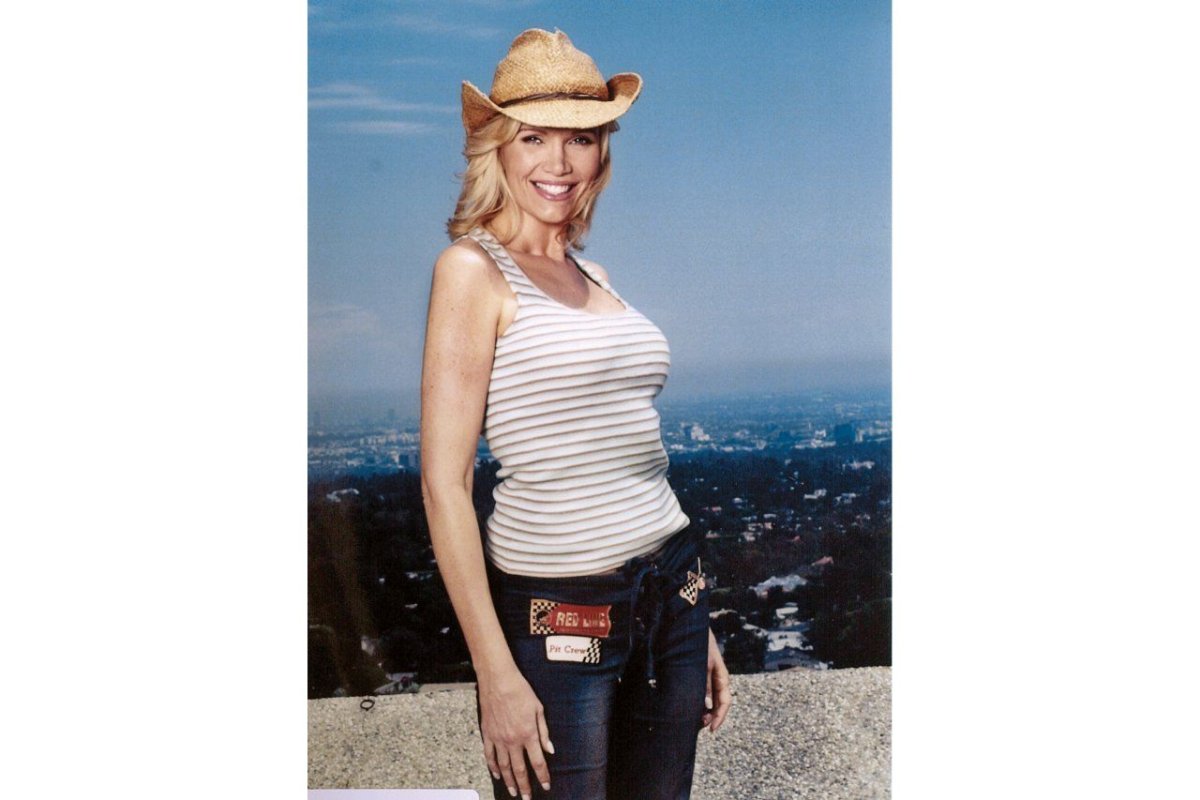

There are two versions of Lana Clarkson, too, equally conflicting. One was the Amazonian blonde bombshell, over six feet tall and admired in B-movie cult circles for her starring role in Roger Corman's 1985 Barbarian Queen—a gorgeous, effervescent party girl, equally talented as an actress and as a comedienne, like her heroine and inspiration Marilyn Monroe.

The other version was the one that Spector's defense team sought to bring out in the trial: the failing actress past her sell-by date, hooked on prescription painkillers, severely depressed, writing suicide emails to her friends, struggling to make her rent the month she died, and reduced to working as a greeter at the front of the VIP room at Sunset Strip's House of Blues for $9 an hour, pulling out chairs for people she'd once partied with—or even once beat out for roles at auditions. The trial I observed, the first one, at times seemed like a battle over which version of Lana to believe.

For me, during the trial, Spector embodied versions of two historical figures and moments I am fascinated by: Oscar Wilde during the period of his own trials, and Napoleon in exile, captive on St. Helena. Wilde in the courtroom wittily playing for laughs under the delusion that if the court would only recognize his genius, he'd go free. Napoleon, his vast empire of a world shrunk to a few small rooms, pacing them endlessly. In Phil Spector, I had both those stories bound up in one man. Back at the castle, on the eve of the trial, his whole world seemed shrunk into a waiting room with him at bay in the corner—another height-challenged man who once bestrode his own universe like a giant. And in court, where I'd watch him going at times into what seemed to be fugue states, I felt I could hear him listening to his greatest hits, and wondering why the court didn't just recognize his genius and let him go.

In one of his letters to me, Spector saw it that way too, sending me this quote: "It is [hardly] possible to do more than hold up one's hands in horror and amazement, and protest most vehemently against the action of the newspapers in condemning him, before he has been tried. No one denies that the so-called 'revealed' and 'released' written evidence against him is appallingly strong. But, until he has been convicted, he is innocent in law, and it is a dastardly and indecent thing for that section of the press, which has never lost a chance of reviling him, to take the present opportunity of venting their spite upon him. It will be almost impossible for him to receive a fair trial. A giant among pigmies, he has, naturally, been cordially hated by all the mean and little people, and they now think to increase their own size and importance by belittling his."

Spector continued: "dear vikram: sound familiar? it could have been written about yours truly. but it was written in 1895 in a French publication about Oscar Wilde, just prior to his trial. and, by the way, he was convicted, and served two years, at hard labor. and died at the age of 40. love, phillip."

Like Wilde on trial, Spector's sense of humor could push its way in at exactly the wrong time. To one of his pretrial procedural hearings Spector wore a giant Jewfro, a wig that launched a thousand jokes (as he told me, "Jay Leno said it looks like I'd been electrocuted already!"), but he seems genuinely to have believed it would merely provide some light relief to a boring if not grim little courtroom appearance. And when, on camera, I asked him, "What happens if they find you guilty?" he couldn't resist some black humor: "I'll be in a jail with Bubba. Six-foot-eight Bubba, he'll be my husband ... and he'll carve me a new a--hole."

I immediately said, "Phil, you've got to stop saying things like that on camera. They'll subpoena my footage, and you saying stuff like that will give them a golden opportunity to show the court and the jury that you're not taking the trial seriously. It'll make them hate you more." To which he performed a shrug and said, with perfect timing, "Hey, what you gonna do?"

Of course Spector was taking the trial extremely seriously, and he was terrified of the possible outcome. It's just that whenever an opportunity came up for gallows humor, he'd take it. And as we all know, black humor is very easy to misunderstand. As no doubt this article, in citing it, might be.

Along with his humor, Spector was a master of the tall, or at least the tallish, tale. One time he told me about his interaction with Bob Dylan in the lead-up to George Harrison's Concert for Bangladesh, which Spector helped produce. Dylan hadn't performed in public since his motorbike accident a few years earlier, and apparently was more than nervous. According to Spector, Dylan had locked himself in his New York townhouse and was refusing to come out, even as the concert was about to begin. So Spector went downtown to talk to him, "Jew to Jew." He got to Dylan's door, banged on it with his gun, and insisted Dylan open up or he'd shoot through the door. Dylan, Spector told me, opened the door and went.

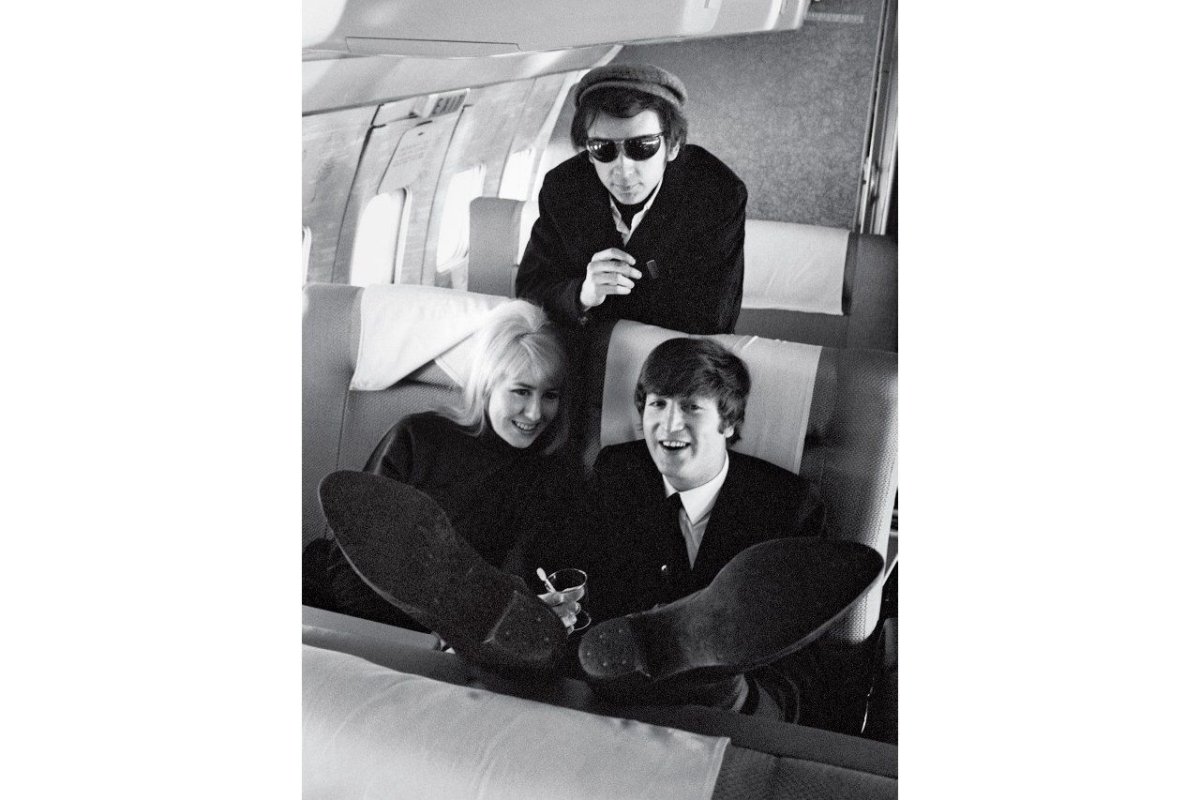

You never know quite what to believe in Spector's stories, but there often seems to be a grain of related fact deep down inside the most unlikely of them. I've heard tell that Spector claims to have brought the Beatles to America. Not true, of course, but I discovered a couple of years ago that Spector was indeed on the plane that brought the Fab Four to the U.S. for the first time in February 1964. My friend Dick Fontaine was on the plane, en route to making his Beatles documentary Yeah! Yeah! Yeah!, and he remembers a tiny guy sitting next to him, in a cap, sweating acridly in terror all through the flight. Sure enough, it was Phil Spector, whose fear of planes is legendary, though it's not clear what his role was on the plane's epochal mission.

His connections with his fellow greats in the rock pantheon notwithstanding, in our conversations Spector came back again and again to his bafflement and rage that they weren't standing up for him now that he was in trouble. Where were the superstars who'd all at one time or another said they owed their careers to his inspiration? Brian Wilson, Tina Turner, Cher, Bruce Springsteen, Keith Richards, and Bono—why weren't they coming out and offering their support, so that the judge and jury and the public could see who he really was? There was no point telling Spector that a character reference from Keith Richards wasn't going to carry a lot of weight with Judge Fidler, who was anyway rigorous in not allowing mention of Spector's artistic career in the courtroom.

When I write about Spector's sense of persecution, I do so in full knowledge that many readers are likely to think that Spector's missing the point. A woman died in his house by a bullet from his gun, after all—and that's a lot more real than feeling dissed by the music industry. And that is true. But I believe Spector's feeling of being slighted is key to understanding who he really is. Even as he sat in his huge living room, with a painting by Picasso on one side behind him and a beautiful big drawing by John Lennon on the other, with the white piano from the Imagine sessions just off on the left, I got the impression that his sense of injustice about how life had treated him was what he felt most keenly.

Anyway, just because you're paranoid doesn't mean that people aren't out to get you. As a good friend of mine in Los Angeles law enforcement told me at the time, between O.J., Robert Blake, Michael Jackson, and Paris Hilton, it was seemingly impossible to send a celebrity to jail. But Phil Spector, with his history of flamboyantly ugly behavior, seemed fated to go down.

Here's what we know about the night Lana Clarkson died, February 3, 2003. Spector, who by and large had been on the wagon for 10 years, for some reason went out drinking that night in Hollywood. He had a woman with him. The House of Blues on Sunset was his third stop. When he came to the front of the Foundation Room, Lana Clarkson, as the door girl, refused him entry. With his strange hair and wearing what seemed to be a woman's white frock coat, he looked like an old bag lady to her. He didn't take this well, blowing up at her and saying he owned the place.

The manager came over to see what the fuss was and recognized Spector, admonished Clarkson that Spector was a very important guest who should be treated like Dan Aykroyd (himself one of the actual owners—that kernel-of-truth thing again), and after many apologies Spector and his friend were seated. Later in the evening, his friend left and Spector gave a cocktail waitress a $450 tip. At which point Clarkson came over and apologized to him again, and Spector asked her to have a drink with him. She said she couldn't till after her shift ended.

And when it did, the CCTV in the House of Blues parking area shows Clarkson walking him out to his Mercedes, and his driver then drove them to Alhambra. A few hours later, Lana Clarkson was dead, slumped in a chair in the hallway of the castle.

During the first trial, in the absence of clear-cut forensic proof that Spector had fired the gun that killed Clarkson, the prosecution relied on establishing Spector's well-known history of threatening people, especially women, with any number of his prodigious collection of guns. The defense kept hammering away at the lack of forensic proof. If Spector had indeed jammed the gun deep into Clarkson's mouth and pulled the trigger, why was there such a negligible amount of blood spatter on the white coat he was wearing when the gun went off?

My documentary, though it focuses primarily on Spector's music, intentionally leaves the audience with the impression the prosecution did not make its case, and that the jury's announcement that they were hopelessly split in the third week of deliberations was an appropriate result: a hung jury. What I didn't go into was my very strong sense that Spector's team of lawyers wasn't being allowed to make their own case: that a suicidally depressed and desperately struggling actress had shot herself, using one of Spector's guns. To my layman's eyes, as I watched potentially exculpatory evidence being blocked from entering the record, I didn't feel Spector was getting a fair trial.

The idea of an awful, flawed man being railroaded for a crime he may not have committed plays to so many of David Mamet's central obsessions. His movie, Phil Spector, inspired by my documentary and starring Al Pacino as Phil Spector and Helen Mirren as his defense lawyer, Linda Kenney Baden, comes out the last week of March.

In his script, Mamet works Spector's eccentricities to the hilt: Pacino plays a maddening figure, crazy as a bug but also a misunderstood genius, and under Mamet's direction, you watch a hard-bitten Mirren gradually warm to Spector and become convinced of his innocence. (Full disclosure: I worked with Mamet on the production as a key consultant.) With Pacino's and Mirren's complex and riveting portrayals, you come away from Mamet's movie thinking that Spector is his own worst enemy even as you are persuaded that there is more than a reasonable doubt about his being a murderer.

I did not attend the second trial, in which Spector was convicted and sentenced to 19 years to life in prison. He's now at California's Corcoran State Prison, where Charles Manson and Sirhan Sirhan are also housed.

He has no further appeals available in the California courts system, but he has one last chance to get his conviction overturned. In the federal court system, with a federal habeas corpus argument. And this is where Spector's already sensational story takes an extraordinary turn. I've interviewed Spector's two appeals lawyers in depth, and this last-chance appeal turns on a major principle of law, which makes Spector's case about something much bigger than the terrible personal tragedy of Lana Clarkson's death and any controversy over Phil Spector's guilt or innocence.

Very briefly, federal habeas corpus as we know it today has its roots in the period immediately after the Civil War when the U.S. government created a legal procedure to protect African-Americans, newly freed and made full citizens, from judicial injustice in the former slavery states. It meant that if a defendant got railroaded in state court, there'd be recourse to appeal to the federal court to get that reviewed and reversed. Federal habeas corpus is designed to keep state courts honest and criminal trials fair. It's not about the guilt or innocence of the petitioner, it's about whether due process was followed in getting him or her convicted. And Spector's lawyers are arguing that due process was violated in Phil Spector's second trial.

The legal details are rather arcane, but the basis of the appeal boils down to this: in the second trial, the prosecution was having trouble getting the crime-scene technician to describe the blood spatter on Lana Clarkson's hands in a way that was unambiguously consistent with Spector firing the gun. If Clarkson had fired the gun, which was the defense's position, the spatter coming out of her mouth would have been on the inside of her hand, which would have been facing her mouth as she pulled the trigger. If Spector had fired the gun, forensics experts agreed, the spatter would likely be on the back of Clarkson's hands.

With the crime-scene technician failing to help the prosecution's argument, they turned to a videotape from an earlier hearing. The technician is still wavering, the take-away unclear, when Judge Fidler intervenes: he declares definitively that he can see more clearly from where he sits, and that she is describing the back of Clarkson's hands.

Spector's lawyers say this intervention by the judge made all the difference between a hung jury in the first trial and Spector's being convicted in the second, as Judge Fidler's videotaped statement is the sole substantive difference in the evidence put forth in the two trials. They say that the taped statement by the judge, which was presented as a piece of evidence to the jury, effectively turned the judge into a witness for one side instead of an impartial overseer. They also charge that the judge's testimony, because it was taped and not live, denied Spector his legal right to cross-examine. Finally, they say that the prosecution put undue weight on the authority of the judge—then serving as a biased witness, in telling the jury that if they didn't believe the crime technician was describing the location of the blood spatter clearly or accurately, they had the judge's statement to consider.

As one of Spector's lawyers, Chuck Sevilla, says, "In my 40-plus years of working in the criminal-justice system, I've never seen a judge used as a prosecution witness as he's presiding over a trial. I've never heard a prosecutor argue that the judge himself corroborates our most important forensic witness ... If we allow a judge to take a role as a witness for the prosecution in this case, is it going to be a green light for judges doing it in other cases? I think the federal court has to step in."

As Spector's other appeal lawyer, Dennis Riordan, says, "It's not a finger on the balance, it's a fist." And David Evans, a highly regarded Los Angeles criminal-defense attorney who is not involved in the Spector case, reflected that "[t]his is a profoundly important issue ... "This case is in front of a very able magistrate judge. If these concerns are not addressed in his decision, one fears for the future of the writ [of habeas corpus]."

Federal habeas corpus has been under assault, largely by Republican lawmakers, for 30 years, as part of their campaign to restrict the appeals process in general. And that's why the outcome of Spector's appeal may be so crucial. I would never have thought that Phil Spector would end up being a test case for a crucial protection of citizen's rights. But as Evans told me, all sorts of key legal victories involve unlikely and sometimes unsavory characters.

Sevilla and Riordan's appeal arguments have been made and the federal habeas corpus magistrate judge is currently deliberating. I'll let Phil Spector have the last word, which he sent me recently: "Hello Vikram. I'm sorry I can't talk to you directly, but this will have to do. My comment on what happened to me at the second trial is simple: I am the only prisoner in America put here by a trial judge who was a witness for the prosecution. That's wrong."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.