Sit with Paul Allen in his office in Seattle and you might take him for the head of a middling actuarial firm. He is 59 and pear-shaped, in black slacks, a white shirt, and blue tie, with his hair cut short above nondescript glasses. His aggressive banality comes as a shock, given his outsize résumé.

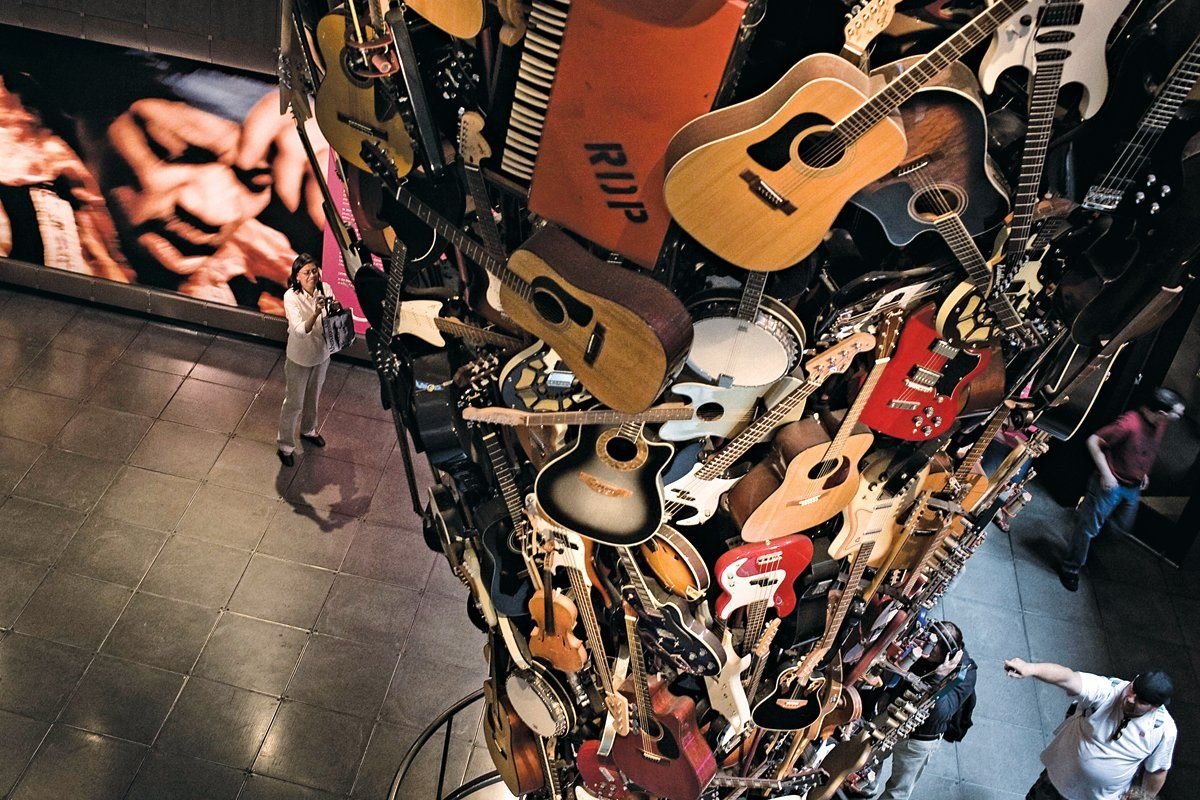

He's the "Idea Man" (self-styled, as per his autobiography) who helped Bill Gates found Microsoft and walked away with billions early on. He's the man who had such a passion for Jimi Hendrix that he built a Frank Gehry museum to house his Hendrixiana. He funded the first commercial manned flight into space, has owned sports teams, cavorted with athletes, and jammed with rockers on his various estates and yachts.

But in his office in Seattle, you might need to be an art critic to get a whiff of his status and wealth. Look around and you spot two gorgeous Calders on a table nearby. Glance through a door and you see one of Rodin's casts of The Thinker; walk through it and you take in Giacometti's bronze Femme de Venise, worth maybe $5 million, as well as a lovely Monet landscape that could have cost several times that. You might also recall the glorious Rothko, glowing in orange and yellow, that you passed on the way to the interview. It has been brought in from Allen's home as the backdrop for this -story's portrait shoot—a canvas now worth something like $80 million, protected from stray elbows by a row of $12 pylons in safety orange. (They go rather well with the Rothko.) There's more wealth here, in these few square feet, than many millionaires amass in a lifetime, and the artworks in sight are only a small part of Allen's hoard.

This legendary nerd (although Allen bridles at a "pocket protector" image) is also an artsy who spends a fair part of his $15 billion fortune on cultural goods—both as treats for himself and for others. "Some of these things you're so taken with that you find it pretty amazing that you could have something like that in your home, and enjoy it every day," says Allen. "That's a pretty amazing thing. On the other hand, you feel that it's better to loan these things out."

With no great fanfare, the secretive collector has started to circulate his treasures to the public—a philanthropic morsel that is part of a larger program of kindness to the arts that so far has stretched to more than $100 million. On Oct. 15, at the National Arts Awards gala in New York, the group called Americans for the Arts is honoring Allen with its philanthropy prize.

Last year, the Chronicle of Philanthropy named Allen the nation's most generous living donor; he beat George Soros and Michael Bloomberg and has been on its top 50 list for a decade. Speaking from his Washington office, Robert Lynch, president of Americans for the Arts, talks about Allen as the kind of honoree "who can inspire others to do more."

In 2010, Allen pledged to give away at least half his fortune, after a nudge from his school pal Bill Gates. Most of the money is likely to go to his many science causes, which have already sucked up something like a billion Allen dollars. But if even a sliver of his pledge ends up spent on the arts, AFA will feel its award was well given. Arts centers across the Northwest are crowded with plaques thanking the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, and more will no doubt have to be carved.

And then there's the part of Allen's wealth that has been transmuted into art, which, in a classic philanthropic move, could get passed on to museums. Allen is on all the "great collector" lists, but the details of what he owns are murky. "I know nothing," says a New York art adviser normally in the know. "It's locked up tight. I haven't seen a level of privacy so intense, and so maniacal." Allen is known for his nondisclosure agreements; his employees should have "No comment" tattooed on their foreheads, to save journalists time.

So his staff seems pleased that Allen himself chooses to make some disclosures. He mentions that his collecting began with antiquities. It moved forward to the Renaissance and a beautiful Madonna by Sandro Botticelli, which he's already lent out. And of course he's got impressionists: tony pictures such as Monet's great Rouen Cathedral: Afternoon Effect, as well as a Renoir painting of a woman reading that last sold for $13 million.

Both of those, as well as a $40 million Gauguin and a lovely pointillist Seurat, were in a show of 28 Allen works put on in his Seattle music museum, Experience Music Project. The collection comes more up to date with that 1956 Rothko, and with contemporary works that Allen now mentions, such as a canvas covered in spots by Damien Hirst. Allen, smartly, sees the piece as speaking to his own techie past: "There's a kind of digitization happening in there that I respond to." He probably doesn't recognize that his Hirst also pokes fun at the kind of rich madman who'd fork out big bucks for a fancy picture of dots, when the artist has made more than 1,000 others like it.

Allen credits his arts interests to his parents: a father at the University of Washington library and a mother who loved books and taught school in Seattle. Allen was born and raised there, and it's where he first met Bill Gates, in front of their high school's computer lab. He grew up with a bit of art: a plaster cast of the same Rodin Thinker he now has in the original, a book on Picasso he cherished. But his great "cultural" awakening came in 1967, when he heard Are You Experienced? on a friend's record player and had his mind blown by Hendrix. ("Mind-blowing" remains a favorite Allen adjective, and just about the only thing that hints of his early days with "Purple Haze.") "Like many people said, it was like hearing music that was written on a different planet," he recalls. Allen's mother gave her teenager a $5 electric guitar, which he struggled to master, and by the summer of 1970, as he claims in his memoirs, "I sported -button-fly purple bell-bottoms, a medallion around my neck and a Mississippi River gambler's hat"—an image so far from the Allen of today that you want a time machine to confirm it.

Allen says he has never stopped strumming, occasionally alongside celebrity musicians such as Mick Jagger and Bono. (Being a billionaire comes with its perks, although "in concert" footage the guitar-playing mogul can sometimes look like a kid working on his times tables.) Allen has founded and fronted a couple of vanity bands—"Grown Men" and "Paul Allen and the Natural Born Swimmers"—and is putting the finishing touches to a second album due out any day. A single from it has a cameo as background music in the male-stripper comedy named Magic Mike, in which Allen does not appear in the flesh. His R&B-ish song calls to mind James Bond themes of the '80s, with lyrics that favor rhyming couplets: Ache inside ... Wounded pride ... Hit and run ... Loaded gun.

Allen says that he made the move toward visual art only after Microsoft went public in 1986, and his vast holdings in the company's stock helped make him, for a while, the world's fifth-richest person. (Allen hasn't gotten notably poorer, but other fortunes have since raced past his. Last spring, Forbes ranked him 48th.)

Allen remembers his first "mind--blowing" visit to the Tate Gallery in London and discovering Roy Lichtenstein there. (Allen now owns The Kiss, one of the pop artist's early riffs on cartoons.) And he speaks of being introduced to more difficult art by his friend David Geffen, the Hollywood mogul and patron. He compares his favorite art to the "free expression and experimental approach" of Hendrix, pointing to Jackson Pollock as a Hendrixian figure "who is completely free and different and so new. He set a new standard and paradigm."

Allen is now "very, very much in tune with what's happening in the art world," according to Tom Venditti, the curator who helps Allen tend his collection and lend it out. (He has been given permission to talk, but it clearly makes him nervous, as though every detail he lets slip was once stamped "Top Secret.") Venditti says that more than 300 Allen works have gone out so far, to 47 different venues, and that the pace of this lending is building. The curator describes Allen as "an art collector, mostly"—Venditti jokes that "we didn't buy Munch's 'Scream,'" with the implication that they could have gotten the $120 million painting if they'd cared to—but also mentions all the "lesser" interests of his boss's.

These include holdings in electric guitars and rock-and-roll curios, in vintage technology and scientific equipment, in science-fiction illustrations and props. (Venditti says he helped Allen acquire Captain's Kirk's first command chair from Star Trek, now on view in the -science-fiction museum that Allen has installed in the basement of his shrine to Hendrix.) And then there are the dozens of old war planes for which Allen has built yet another nonprofit home, on an airfield near Seattle. "The breadth of what interests me sometimes surprises even me," says Allen. "For everybody there are things that resonate with them, and things that don't resonate as much. But there's so much art that does resonate with me, that the more I've got into it, the more I've found that I really enjoy ... People have said to me before: 'But Paul, you like Lichtenstein and you like Monet,' but to me that's not that unusual."

Like all the rest of Allen's assets since he took the Gates-Buffett pledge, his art is fair game for future giving, especially since he has never married or had kids. "With the health issues I've had, I've had to think about it maybe more than some people that are my age," says Allen. In 2009, he was diagnosed with a brutal lymphatic cancer. (He'd had a bout with a different form of it in 1982, which helped push him to leave Microsoft the next year.) The latest drugs put his disease into remission, and if you ask Allen how his health is now, he utters a sotto voce "fine, fine." But the cancer or its treatment has clearly taken a toll: one hour's conversation seems to exhaust him, and he leaves the room walking like a much older man.

The public disposal of Allen's cash looks like it's under control: the well-oiled Paul G. Allen Family Foundation has a clear mandate and program, which, for the arts, includes encouraging "dynamic adaptability" in the institutions it funds and promoting "content-infused art," says Sue Coliton, the foundation's businesslike vice president. Where Allen's own art will fit into this giving still seems in doubt. "Of course when you're no longer around, someone else or the public should enjoy it," Allen says, but he doesn't like donating where others have already and points out that the world hardly needs another art museum.

He aims for something more high impact than that: "The works of art that you really find amazing, you should try to tell people, 'This is really amazing! Can you see what I'm seeing here, because it's -really fantastic!'" He says he's considering options that will help communicate this amazingness and make people realize they can have easy access to it in their own lives. But as for the details of what he has in mind, "I've got some ideas, but there's nothing we're prepared to release."

Even at his most voluble, Allen can seem to have signed his own nondisclosure agreement.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.