Bloomberg was everywhere, like Bloomberg likes to be.

In New Hampshire, on a Tuesday night in October, Bloomberg Television was sponsoring its first-ever presidential-primary debate. A Bloomberg-branded hospitality tent had been erected to promote new products called Bloomberg Government and Bloomberg Law, and amid stacks of free Bloomberg hoodies, as name-brand journalists for Bloomberg News and Bloomberg View munched on lobster rolls, there stood off to one side a replica of the Bloomberg Professional terminal. It might as well have been a shrine. "The Bloomberg," as the financial-data machine is known, is a computer so omniscient that God would use it if he day-traded, and the $6 billion it funnels into the company every year had paid for everything in sight.

Other media outlets don't have a cash cow anything like this. And BGov chairman Kevin Sheekey couldn't help but rub it in, walking up to the terminal's blinking prompt and challenging one guest: "Why don't you look up the price of the New York Times Co.?"

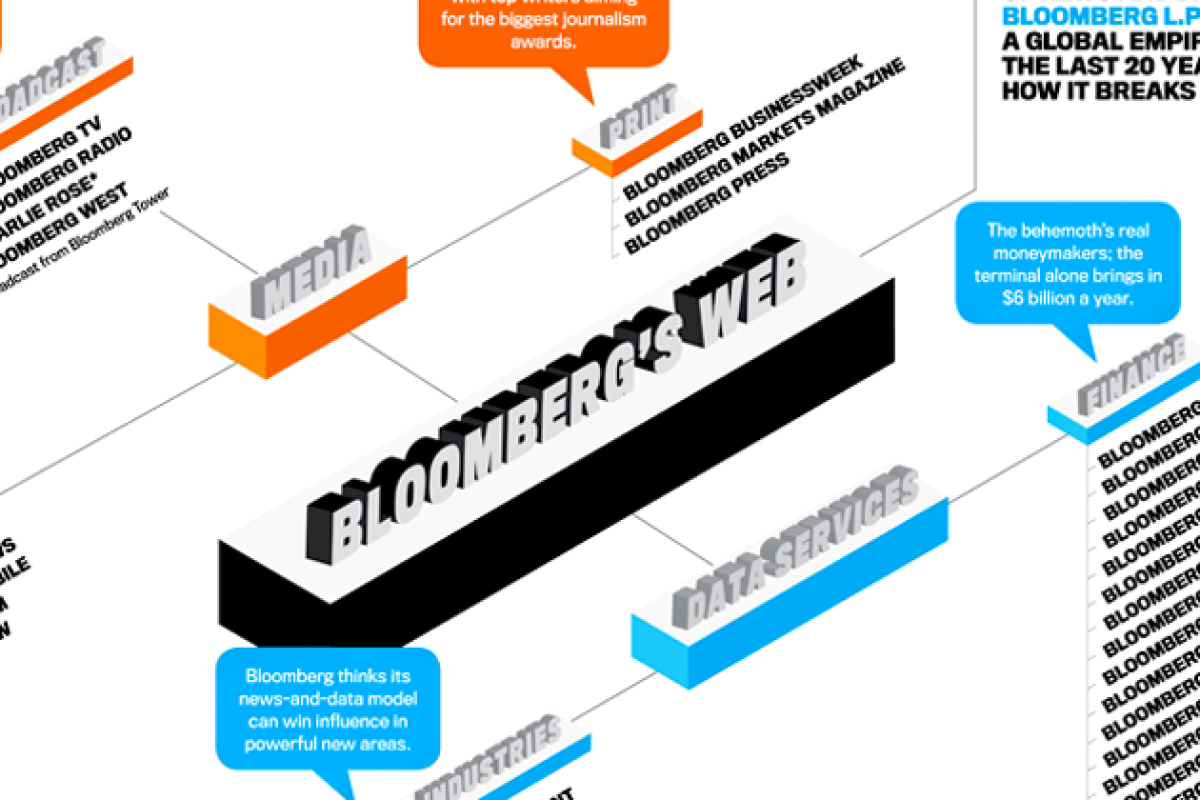

Ouch. As most of the news industry withers, Bloomberg is booming. Terminal money, which accounts for 80 percent of revenue, has helped the company hire more reporters and editors than anyone else on the planet—more than 2,700 of them—over the last 20 years, from Abuja, Nigeria, to Zagreb, Croatia. More recently it has launched powerful new tools for lobbyists, lawmakers, and other power brokers. Long averse to acquisitions, Bloomberg has also started buying up things it covets, like Businessweek magazine and, just this August, the legal-political research behemoth BNA. There is talk that the Financial Times might be its next meal.

All of which means that by the time Michael Bloomberg, 88 percent owner of Bloomberg L.P., leaves New York's City Hall two years from now, he will have his name stamped on some instruments of surprisingly deep influence.

But this isn't just another story about a company beating the odds and growing in a down economy. Bloomberg the company is not all that well known beyond Wall Street; its expansion has managed to be both subtle and seismic, and could fundamentally alter not just the kind of news Americans get but the events in the news themselves. While one guiding principle of traditional journalism is to "comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable," Bloomberg has made its money comforting the comfortable—plying high-spending traders and other business insiders with all the data they need to do their jobs with confidence.

Now it's taking that formula to Washington. When Bloomberg bought BNA for $990 million in August, most Americans had never heard of the Bureau of National Affairs or its 350 newsletters on topics like tax, health care, and labor. It doesn't produce popular scoops—instead it churns out nuts-and-bolts information on things like an appeals-court judge's ruling on a patent dispute; when the House Appropriations Committee will mark up an EPA funding bill; and how telecom giants will benefit from a moratorium on wireless taxes. Which means every lawyer, lobbyist, and law-maker in the capital depends on BNA's proprietary data to do his or her job and gain an edge over competitors. From that angle, BNA is just the kind of company that Bloomberg— already a powerhouse among business insiders—could use to extend its power into new markets, in this case the "influencing community" inside the Beltway.

"It's utterly logical," says Steven Brill, the founder of Court TV and American Lawyer. "I lusted after BNA when I owned all my legal publications, because it's very high-margin, high-priced, and specialized information."

Bloomberg had recently launched two new subscription services online, BLaw and BGov, each with the company's trademark approach of seducing professionals with a fire hose of data, custom-built analytic tools, and proprietary news until they feel unable to make key decisions without consulting Bloomberg. But in the crowded market for insider Beltway news, BGov and BLaw were still finding their footing when BNA put itself up for sale.

Now Bloomberg can feed BNA's sought-after data directly to BLaw and BGov subscribers. The result: a one-stop shop for lobbyists to game the system.

Let's say a lobbyist for a coal company wants to squash any legislation that affects his employer's mining operations. He logs onto BGov.com (the cost is $5,700 per year) and is automatically alerted to breaking news of a just-introduced energy bill. The data drill-down begins. BGov shows the lobbyist how similar legislation has fared, what subcommittee the new bill will face and when, who the key congressmen are, and how they have voted in the past. The lobbyist calls up information on the swing vote's upcoming election contest: it's competitive, and the congressman is behind in fundraising. Lists of major donors—who might be induced to contribute or, better yet, place a call to the officeholder himself—are a click away. These political pressure points and a thousand more are how lobbyists make their mark, and Bloomberg thinks BGov can deliver them faster than the competition.

The BGov headquarters in Washington mashes up the standard Bloomberg aesthetic—snack stations, neon hues, an obsession with fish tanks—with the cement-floor look of a startup tech company. The space is half empty, with row upon row of identical Bloomberg terminals set up and waiting to be inhabited by programmers, reporters, and salespeople.

As more of Washington subscribes, Bloomberg can hire more journalists to swarm the Beltway. The result will be situations where Bloomberg News reporters cover a bill's path through committee, as committee staff use BGov to research their opponents' weaknesses, or where Bloomberg News reporters cover a federal trial, as the case's attorneys use BLaw to comb through precedents.

Expanding into the legal and political realm is a logical outgrowth of the business that Michael Bloomberg started in 1981. Fired from an investment bank, he envisioned a product that would deliver essential data to Wall Street types faster than anyone else: the Bloomberg terminal. By 1990, addicted investors were clamoring for news to give all the numbers context, and over the next two decades Bloomberg built a global editorial network, with more than 150 bureaus in 72 countries. The CEO, Dan Doctoroff, calls it a "virtuous circle of influence." Terminal loot pays for the news divi- sion, which breaks market-moving stories, which makes the terminals that much more worth their astronomical fee of about $20,000 per user per year.

In 2005 the company moved its headquarters into Bloomberg Tower, a light-soaked, 55-story Manhattan skyscraper where the cheer (see: snacks, fish tanks) is only partially offset by the dystopian monitoring of employee movements and keyboard usage. The place has the babbling hum and customized-oxygen feel of a shopping mall, in which all the teenagers have been replaced with valedictorians.

For 2010, revenue approached $7 billion. Comparisons to public companies are inexact, but the New York Times Co. reported $2.4 billion in revenue for 2010, and Thomson Reu-ters $13 billion. But while Reuters's operating margin is 19.6 percent, and the Times Co.'s is about 10 percent, Fortune estimates Bloomberg's to be an astonishing 30 percent.

With financials like that, Bloomberg can experiment in any direction it wants. "It's not about influence for influence's sake," says Doctoroff. "It is all pursuant to a very disciplined corporate strategy." Bloomberg headquarters has no offices, not even for the CEO, and a jacketless Doctoroff is giving an interview in a fuchsia-tinted glass terrarium just behind his desk, which itself is only steps from the main employee elevator bank. He leaves to retrieve a wire model of a solar system to illustrate his point. "The terminal, which today represents about 80 percent of our revenues, is the sun in our solar system," he says, placing both hands on the large yellow plastic orb. It has a little terminal logo on top. "It is for us the life-giving force." Other, lesser business properties merely orbit the terminal, basking in its technology, capabilities, and sales relationships.

Doctoroff points to magazines. The company has published the upscale Bloomberg Markets since 1992; in 2009 Bloomberg bought the much more mainstream Businessweek, and now uses it to leverage interviews with CEOs. In September, Amazon boss Jeff Bezos gave the magazine an exclusive interview about a secret tablet device. "We released the cover story on the terminal first. It moved Amazon's stock like 5 percent," says Doctoroff. "We would not have been the first call of Jeff Bezos to announce the Kindle Fire if we had only been writing for our 313,000 terminal customers. Because he didn't want to just speak to financial professionals. He wanted to speak to the world."

Bloomberg L.P. owns most kinds of news outlets, including TV, radio, magazines, mobile, the Web—every medium except newspapers. There have been occasional bursts of chatter about Michael Bloomberg buying a newspaper. First it was The New York Times; lately speculation has turned to the Financial Times, which is more of a natural fit in subject matter and also a publication much more likely to be sold by its parent, Pearson. Though it accounts for less and less of the education giant's total revenue, the FT is not a weak paper. Its business journalism is highly regarded. It is one of the few newspapers to successfully charge for its content online. And its editorial page could provide a prominent boost for Bloomberg View, an opinion-journalism site meant to channel Michael Bloomberg's centrist politics. It's also the arm of the company he seems most likely to engage with after leaving City Hall: BView opened up shop not at Bloomberg Tower but inside the building that houses the mayor's personal Bloomberg Philanthropies effort.

BGov's Sheekey, Irish and mischief-eyed, seems to enjoy fanning the acquisition rumors. He's not just another company exec—a top Michael Bloomberg lieutenant, Sheekey ran his three mayoral bids (and explored a run for the presidency in 2008). "They'd get much more interesting if the company ever bought a newspaper," he says, out of the blue, referring to the View columnists. "Was that on the record?"

An FT spokesperson declined to comment.

Who could argue with broadening Bloomberg's appeal? Actually, plenty of people inside the company do. The terminal business doesn't just work well; it works so well that legacy Bloomberg staffers argue against any initiative that distracts in the slightest. Journalism awards and nebulous influence don't bring in terminal subscribers. "There's a tug of war within the company—there are people inside who don't want to broaden, who say the core business is all we need, why waste our time," says one former Bloomberg executive. "The money is with the traders, but the influence lies well beyond the traders." Internally, staffers tell of tension between longtime Bloomberg News editor Matthew Winkler and Norman Pearlstine, a veteran of Time Inc. and The Wall Street Journal. Pearlstine was hired in 2008 to put a friendlier, more readable face on Bloomberg's content, which for years has been packaged for the addled brains of traders. (There is a blog, Strange Bloomberg Headlines, that compiles some of the more dada-esque keepers: "Fed Pays Lip Service to Beef to Skirt Ridicule"; "GE Beating S&P Sets Profit Goal After Immelt Decade Skirts Abyss.") A company spokesman says there is no tension between the two executives.

Incremental scoops that move a company's stock price are still the coin of the realm, but star imports like Daniel Golden, a Pulitzer winner at the Journal, are showing the dividends of more ambitious reporting. A team he led won a George Polk Award in February for an investigative series on for-profit colleges. Another blockbuster story on insurance companies profiting from the deaths of U.S. soldiers, by David Evans, was a finalist for a 2011 Pulitzer.

Events like the GOP primary debate in October are understood to be crucial chances to make a first impression with Americans who have never heard of Bloomberg. An estimated 1.3 million tuned in, a record high for Bloomberg TV. It was another successful foray into politics. More is coming: the company plans to cover the 2012 presidential campaign heavily and will spend lavishly at the party conventions. "I think the Bloomberg guys are very, very smart—and really wealthy. Some of the stuff they do down here I think is probably a rounding error on their books," says Robert Allbritton, the owner of Politico, another outlet that came out of nowhere to dominate news in Washington. "But you don't get wealthy making mistakes."

It's impossible to talk about the aspirations of Bloomberg the business without addressing Bloomberg the man: it is a company owned by a politician, buying companies that influence politicians. For the decade that he has been mayor of New York, he has been officially barred from determin- ing the direction of the company he founded. (Behind the scenes, he does have his say on top hires, acquisitions, and projects that pique his interest, like Bloomberg iPad apps.) When the mayor reenters civilian life on Jan. 1, 2014, his admirers believe his power will only grow.

"City Hall holds him back. He stands to become something much larger after he leaves office," says Sheekey. "Mike Bloomberg has the ability to be the best parts of Bill Clinton, Rupert Murdoch, and Bill Gates all rolled up into one."

A statesman with a media empire and billions to give away: Michael Bloomberg has his own power apart from Bloomberg L.P. And while the company insists he will not return to active management, the man and the company remain entwined—from fish tanks to editorial judgment to real estate. Bloomberg Tower was supposed to be all the space the company would ever need in New York. In February, though, it leased an additional 400,000 square feet at a stately building on Park Avenue. Its previous occupant? Altria, the tobacco company, which left New York in part because of the Bloomberg administration's smoking ban. Where the logo of the mayor's foe once hung, you can expect to see his name.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.