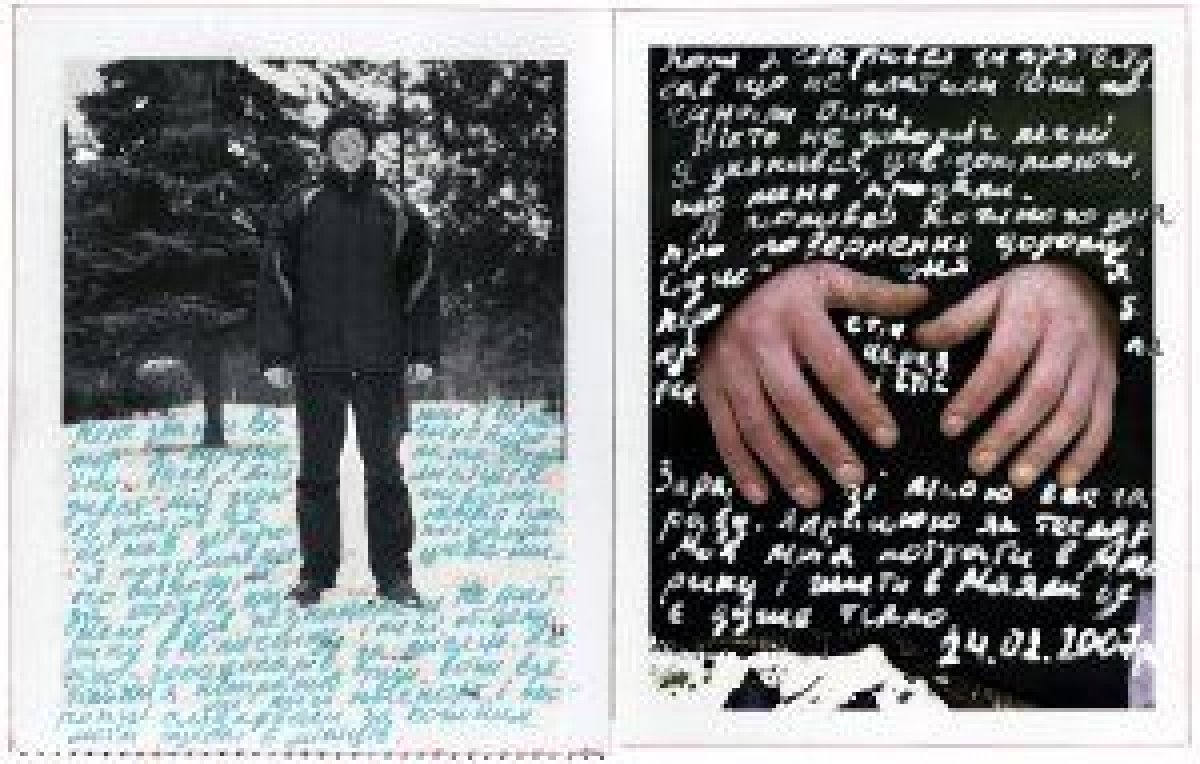

In the shadow of ornate mausoleums and marble tombs, rows of wooden crosses are planted in the dirt, bearing no names, only numbers. Three young men were recently buried in an anonymous grave in this cemetery on the Italian island of Lampedusa. Little was known of them, except how they died—trapped under the hull of a smuggler's ship that crashed onto the rocky shore. The men carried no passports and no papers, though one had a picture of a young woman in his pocket, and another, a folded letter rendered illegible by seawater.

The island priest, Father Stefano Nastasi, photographed the dead men as he has all the nameless who have drowned off the coast during these last few months, storing their portraits at the church rectory in case someone comes in search of a lost relative, he says. "Right now, though, the families probably still think they made it."

No one knows how many people have died trying to make it from North Africa to Europe. Human traffickers don't keep passenger lists, and authorities can only guess at the numbers of migrants based on the size of the capsized ships. But this much is clear: this is one of the deadliest years on record. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that in the past two months alone at least 1,600 people have died at sea as they fled their countries for European shores.

Lampedusa's coastline is marred by the carcasses of capsized boats; the port is filled with shipwrecks, some with blankets, children's toys, and jackets still on board. Deaths in these Mediterranean waters are now so common that fishermen routinely snag corpses in their nets. But to avoid the lengthy bureaucracy that goes with reporting the morbid catch, they often throw the bodies back in the water. "I can't afford to have my boat sequestered for the season," says one fisherman who didn't want to give his name. "They won't get any better burial on land if we bring them in."

Ibra, a 17-year-old from the Ivory Coast, recently set out from Tripoli. Once at sea, the ship's engine went out and the refugees drifted for days before a fisherman summoned the Italian coast guard. By then, however, several people had already died, including a pregnant woman. "There's no reason to keep a dead body on board under the hot sun," says Ibra. "We emptied their pockets and buried them at sea."

The massive wave of migration—and the attendant deaths—are hardly surprising. Libya is a key transit country for African migrants trying to go to Europe, and until recently, European leaders supported Col. Muammar Gaddafi with economic agreements because Gaddafi—as he repeatedly reminded everyone—controlled the spigot on the flow of African migration. During a state visit to Rome last year, Gaddafi's threats were hardly subtle. "We don't know what will happen—what will be the reaction of the white and Christian Europeans faced with this influx of starving and ignorant Africans?" Gaddafi said as he stood next to Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. "We don't know if Europe will remain an advanced and united continent or if it will be destroyed as happened with the barbarian invasions."

When NATO bombardments against Libya began, Gaddafi vowed to "unleash an unprecedented wave of illegal immigration" on Europe. And the ships have been arriving from Libya since.

In the first five months of 2011, more than 45,000 people made their way to Lampedusa—more than 10 times the total number of last year. Thousands of others have arrived on nearby Pelagian islands, as well as Sicily and Sardinia. One boatload of Tunisians made it all the way to the Italian mainland, docking about 50 kilometers south of Rome. If the war in Libya continues, hundreds of thousands more are expected to make the perilous journey in the coming months.

Some refugees come for economic opportunity, having made it to Libya from other poor North African countries or sub-Saharan Africa. Others are fleeing war and unrest in Libya and beyond. But perhaps most disturbingly, human-rights groups report that soldiers loyal to Gaddafi are rounding up people and forcing them onto boats at gunpoint. According to UNHCR and Save the Children representatives who have interviewed scores of survivors, the soldiers give navigational instructions to random passengers before towing the ship to open waters—presumably the idea is to create a humanitarian catastrophe, thereby putting more pressure on Gaddafi's erstwhile European friends.

The journey takes about four days, and conditions on the ships are often horrific. There is little food and there are no toilets on board, and pregnant women are forced to insert catheters before boarding so their urine won't "poison" the superstitious men. One pregnant woman, Madeline Adebisi, recently made the journey—involuntarily, she says. When the bombing of Libya began, Adebisi's husband left Tripoli in search of work after losing his job, and the 32-year-old Nigerian woman was left living with a group of other African women who, like her, had lost their jobs in a hospital with the advent of the war. Soldiers loyal to Gaddafi came to where the women were living and forced them to relocate to a small house near the port. After a few days, they were pushed onto a boat with hundreds of others in the middle of the night, and set to sea.

Three days later, having already tried to dock on the island of Malta, the ship lost its rudder off Lampedusa's shore. Unable to steer, the captain abandoned the wheel, and the ship smashed onto the rocks a hundred meters from the Door to Europe statue, erected to memorialize migrants who have died at sea trying to get to the continent. "We heard the screams coming from the rocks," Lt. Marco Persi of Italy's military police tells NEWSWEEK. "They just kept screaming and screaming, calling desperately for help. I was so worried we would lose some of those babies."

The coast guard's spotlights illuminated a terrifying scene of children and pregnant women fighting for survival in the churning sea. Rescuers plucked hundreds from the water.

"I thought I was dead that night when the boat crashed. I saw this bright light, and I was sure my life was over," says Adebisi, who is now living in a refugee center in La Spezia on the Ligurian coast. She is about to give birth, but has no idea if her husband is dead or alive—she has not heard from him since April, when he left Tripoli.

Migration by way of Lampedusa is not a new phenomenon. But the number of people this year who have made their way to Europe via the island is unusual. The uprising in Tunisia that began in December fueled the first wave. A second wave began arriving in late February, when migrant workers from sub-Saharan Africa, who had been working in Egypt, fled the unrest there. NATO's bombardment of Libya, which began in March, propelled the third wave, with tens of thousands of people—Libyans and migrant workers in the country—fleeing across the border to Tunisia or across the sea to Lampedusa.

Under the Geneva Convention, political refugees become wards of the country where they land. But economic migrants can be deported back to their nation of origin. And in March, Italy and Tunisia reached an accord in which Tunisian authorities promised to stem the flow of economic migrants; more than half the Tunisian arrivals were deported back to Tunisia; the rest were given six-month visas, allowing them to travel within Italy and, in theory, through Europe's Schengen (open border) countries.

The move prompted France—the target destination for most French-speaking Tunisians—to start patrolling its border with Italy, opening a fierce European debate about the viability of Europe's open-border Schengen Agreement. The EU's home-affairs commissioner, Cecilia Malmström, ruled that European countries could reinstate internal border controls under "very exceptional circumstances, such as where a part of the [EU] external border comes under heavy unexpected pressure." The ruling provoked an angry Italian reaction. Roberto Maroni, the interior minister, threatened theatrically that Italy would pull out of the European Union, quipping, "It's better to be alone than have friends like these." Effectively, he said, the ruling would ensure that Italy alone would be left to deal with the refugee crisis. "Europe is not doing what it said it would do," Maroni complained at an EU summit. "There is a war in Libya, and as long as it goes on, refugees will keep on coming. This is a problem that we cannot manage alone."

At one point this spring, migrants and refugees topped 10,000 people in Lampedusa, filling every habitable—and inhabitable—space on the island. About 3,000 people were crammed into a detention center built to hold just 800, and refugees were sleeping in doorways and on plastic sheets under trucks during spring's torrential rainstorms. The refugee agencies ran out of food, and the island's water supplies were severely tested. Berlusconi visited Lampedusa in March promising to nominate the island for a Nobel Peace Prize, and vowing to "become a Lampedusan."

Today, very few boat people stay on Lampedusa, where the detention center is reserved for women and unaccompanied minors. Instead, within 24 hours, those who arrive are packed off by ferry to the mainland, where they are sent to refugee centers around the country. Some centers are tent camps, others military bases. But most all of them are bleak and overcrowded.

Here, behind barbed-wire fences, people await judgment for political asylum, temporary visa, or deportation.

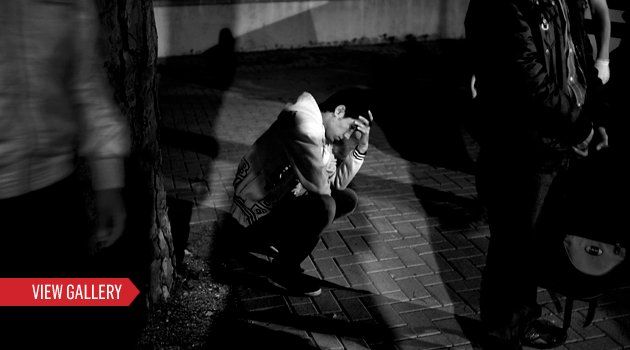

Like Faker Gazzel, many of those who make it from Lampedusa to mainland Europe head for the border town of Ventimiglia, trying to cross into France. Gazzel, a 23-year-old whose brother was killed during the uprising in Tunisia, landed on Lampedusa in February; it took him almost two months to travel the more than 1,000 kilometers north to Ventimiglia. Since April, though, he has been stuck there, even though he holds a temporary visa allowing him to travel to France. Each night Gazzel and his friend board one of the late-night trains headed for Nice; each night they are kicked off the train by French officers who carry billy clubs and wear surgical gloves as they search for Africans aboard the train. "Tunisia is ruined for me," Gazzel tells NEWSWEEK. "Life will be much better in France—if I can get there." He has little money left and spends his afternoons listening to Arabic music on a small radio, drinking red wine out of a cardboard box under a tree on the river bank.

For those suspended in this borderland, the past and the future, sharing stories of maltreatment at the hands of the French police is a way to pass the time.

Ammar Rabaari, 26, takes his front tooth out of his pocket and holds it in the palm of his hand. "The French police knocked it out," he says, showing a toothless grin. His legs are cut and bruised, and his hands are scarred and swollen. Rabaari, a Tunisian, made it to Paris by train in March, living with his brother for almost two months before police caught up with him. One night in early May, French officers arrested him and a group of his friends on a Parisian street. According to Rabaari, the police beat them up before putting them on a train back to Ventimiglia. He is undaunted, though, and will try for Paris again.

His traveling companion is a former hotelier from Tunisia named Tahre Tabi who lost his job when the revolution halted tourism in that country. "I have taken my family's savings to start a new life and bring them over. I cannot fail," the 33-year-old Tabi says. "I never thought about coming to Europe before the revolution, but now I don't have a choice but to stay and try to make this work."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.