"If you want to get the Mormon view of the extended Mormon moment..." The New York Times declared in an article Thursday, "there are few better places than this combination of a white-shirt pilgrimage to Mecca and a G-rated version of Bonnaroo."

The setting described by the Times' Peter Applebome is the Hill Cumorah Pageant, a big-budget production put on annually by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that tells the story of its sacred text, the Book of Mormon. The show, which is staged at the foot of the hill where Joseph Smith says he found ancient prophetic writings recorded on golden plates, draws thousands of Latter-day Saint viewers from across the world each summer. The show is drawing national attention this year partly because of another popular - albeit significantly less G-rated - Mormon-themed musical on Broadway. That production's success, along with the presidential campaigns of two LDS candidates, have shed an unusually bright spotlight on the Mormon community, a phenomenon Newsweek examined in its June 13-20 cover story, below.

Say what you will about him, but Mitt Romney doesn't do, or not do, anything by accident. Take June 2, when the former Massachusetts governor traveled to a quaint farm in Stratham, N.H., to "announce" his foregone conclusion of a 2012 presidential campaign. Romney has to overcome several mountainous challenges before capturing the Republican nomination, and so he spent most of the day trying to reduce them to molehills. To thaw his icy persona, Romney passed out his "famous" family chili and surrounded himself with bales of hay. To account for his moderate governing record, he reminded listeners that the Bay State legislature was "over 85 percent Democrat." And to soften concerns about "Romneycare," he admitted it was "not perfect," then repeated his mantra about it being "a state solution for a state problem."

But there was one challenge—a challenge that could alienate the kind of Republicans who vote in early primary states such as Iowa and South Carolina—that Romney didn't address: his Mormon faith.

No question the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is "having a moment." Not only is Romney running again—this time, he's likely to be competing against his distant Mormon cousin Jon Huntsman Jr. The Senate, meanwhile, is led by Mormon Harry Reid. Beyond the Beltway, the Twilight vampire novels of Mormon Stephenie Meyer sell tens of millions of copies, Mormon convert Glenn Beck inspires daily devotion and outrage with his radio show, and HBO generated lots of attention with the Big Love finale. Even Broadway has gotten in on the act, giving us The Book of Mormon, a big-budget musical about Mormon missionaries by South Park creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone and Avenue Qwriter Robert Lopez that, with 14 nominations, is expected to clean up at the Tony Awards on June 12.

But despite the sudden proliferation of Mormons in the mainstream, Mormonism itself isn't any closer to gaining mainstream acceptance. And nowhere is the gap between increased exposure and actual progress more pronounced than in politics. In recent weeks NEWSWEEK called every one of the 15 Mormons currently serving in the U.S. Congress to ask if they would be willing to discuss their faith; the only politicians who agreed to speak on the record were the four who represent districts with substantial Mormon populations. The rest were "private about their faith," or "politicians first and Mormons second," according to their spokespeople.

The evasiveness extends even to presidential candidates. In late 2007 Romney traveled to Texas A&M to soothe evangelicals with a speech that downplayed the distinctiveness of Mormonism. "It's important to recognize that while differences in theology exist between the churches in America," he said, "we share a common creed of moral convictions." Since then, Romney has rarely commented on the subject.

The more moderate Huntsman, meanwhile, has repeatedly deflected attention from his Mormon roots, telling NEWSWEEK in December that religious issues "don't matter" and that the LDS church doesn't have a monopoly on his spiritual life. He and his wife "draw from a lot of sources for inspiration," he said. "I was raised a Mormon, Mary Kaye was raised Episcopalian, our kids have gone to Catholic school, I went to a Lutheran school growing up in Los Angeles. I have [an adopted] daughter from India who has a very distinct Hindu tradition, one that we would celebrate during Diwali. So you kind of bind all this together."

One could argue that Romney and Huntsman, like their Mormon colleagues in Congress, are right to take religion off the table; after all, many politicians are all too eager to exploit it. But ignoring voters' concerns about the Mormon faith won't make them go away—and by trying, Romney and Huntsman may miss an unprecedented opportunity to dispel misconceptions, blunt biases, and make real progress. A new Pew poll finds that nearly a quarter of respondents would be less likely to vote for a Mormon presidential candidate. And then there's the independent anti-Mormon ad mentioning polygamy that helped sink Matt Salmon's bid for the Arizona governorship in 2002. "A lot of people still don't completely understand what we [Mormons] believe," Salmon tells NEWSWEEK. "In the voting booth, they will use whatever factor they can."

In a vacuum, some people will inevitably conclude that Mormonism is too weird for mainstream America. But just because Romney and Huntsman aren't making the case for their faith doesn't mean there isn't a case to be made. The pro-Mormon argument doesn't have anything to do with the quirkier aspects of the sect's history and practices (special underpants, magic spectacles); the accouterments of any religion can seem wacky when scrutinized in the public square. Instead, it centers on the distinctive values and characteristics that have come to define Mormons outside the church walls—in their communities, in their careers, and in the culture at large. Those inclined to think of Mormons as a band of zealots bent on amending the Constitution to outlaw cappuccino may never be convinced. But the rest of us might benefit from hearing the country's most prominent and influential Mormons tell the truth about their faith: that the distinctiveness of the Mormons is actually the secret of their success.

Mormonism's astonishing growth from its founding 181 years ago in upstate New York to its current status as the fourth-largest religious denomination in America, with just over 6 million members domestically and about 14 million worldwide, has been fueled by a ferocious underdog energy derived from an experience of brutal persecution. The hostility was largely a reaction to the new religion's long list of unusual beliefs and practices. Mormonism's founder, the self-declared prophet Joseph Smith, claimed to have translated a new work of scripture (the Book of Mormon) from text written on golden plates he found buried in the ground. The book told the story of an ancient Israelite civilization in the Americas, including a post-resurrection visit from Jesus Christ. Many other revelations followed, including the most notorious of all: the one advocating "plural marriage," or polygamy.

The sect's unusual beliefs, like the wives of its leaders, multiplied rapidly, provoking opposition everywhere the Mormons turned. First they were chased from Ohio, then from Missouri, where Gov. Lilburn W. Boggs, fearing the church's opposition to slavery as much as its embrace of polygamy, declared that "the Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the state, if necessary, for the public good." The expulsion from Missouri led to Illinois, where Smith and his brother Hyrum were murdered at the hands of a mob on June 27, 1844.

The sect might have perished then and there had Brigham Young not stepped in to succeed Smith, leading its members on a grueling 1,300-mile exodus from the boundaries of the United States to the barren desert south of the Great Salt Lake. Even after the church officially abandoned the practice of polygamy in 1890, opening the door to statehood for Utah, Mormons remained very much on the cultural and religious margins.

Today the legacy of that marginalization continues to mark the Mormon outlook on the world. "As somebody who grew up in Utah," says Dave Checketts, the Mormon former CEO of Madison Square Garden, "I always felt like there was a little bit of a chip on the shoulder. We feel like we're really good citizens, good people, and misunderstood." Social and cultural insecurity has also served as a goad to Mormon productivity and achievement. "If you look back at the church's longtime history," notes Checketts, "there's evidence of a certain level of diligence and hard work and a will to overcome adversity."

The desire to avoid asking for assistance from non--Mormons has also influenced the church's structure, which requires nearly every member to contribute to the common cause. Mormons worship together for hours on Sundays, perform spiritual and economic outreach to members of the Mormon community, and pay a tithe (one 10th of their income) to the church. Some spend additional hours performing secretive rituals and sacraments (including vicarious baptism for the non-Mormon dead) in specially consecrated temples. In an age of spiritual consumerism, when many people regard religion as a therapeutic lifestyle aid, faith is often expected to serve the individual. For Mormons, it's the other way around.

The result is an organization that resembles a sanctified multinational corporation—the General Electric of American religion, with global ambitions and an estimated net worth of $30 billion. The church runs and finances one of the largest private universities in the country (Brigham Young University). Many members serve two-year missions abroad for the church, acquiring fluency in foreign languages (and foreign cultures) along the way. (Mitt Romney learned French on his mission to France, while Jon Huntsman picked up Mandarin Chinese in Taiwan.) More than many other faiths, the Mormon church prepares its members to engage intelligently with the broader culture and the wider world.

But the roots of Mormonism's distinctiveness go beyond the church's history and organizational structure. They go all the way down to some of the church's unique theological doctrines. The Mormons believe, for example, in "eternal progression," which means both that God himself was once a human being and that we can follow his example to evolve into gods ourselves. This progression toward ever-higher stages of divine perfection extends beyond death, continuing into the afterlife.

For Kim Clark, a Mormon and former dean of the Harvard Business School, this doctrine explains a lot about the church's drive toward economic and educational achievement. "Your whole eternal identity as a person is defined by eternal progression," says Clark. "We know that…there will be opportunities to grow and learn and become like our heavenly father, to do what he does. That's a very powerful thing."

Theological commitments also influence the way members of the Mormon church engage in politics. Members vote Republican in overwhelming numbers. (The McCain-Palin ticket carried heavily Mormon Utah with 63 percent of the vote.) It's hardly surprising that support for low taxes and a minimum of government regulation would appeal to a community that once endured severe government-sponsored oppression. Congressman Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) sees an even deeper connection between his faith and his economic and political views. According to Mormon tradition, God and Satan fought a "war in heaven" over the question of moral agency, with God on the side of personal liberty and Satan seeking to enslave mankind. Flake acknowledges that the theme of freedom—and the threat of losing it—runs through much of Mormonism, and "that kind of fits my philosophy." (Although Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid has declared, "I am a Democrat because I'm a Mormon, not in spite of it," his is a minority view among members of the faith.)

On social issues, many Mormons enthusiastically take part in what evangelical activist (and former Nixon accomplice) Charles Colson calls the "ecumenism of the trenches"—the practice of conservative Protestants, Catholics, and Mormons toiling side by side as allies in the culture war against secular liberalism. Still, the differences, and tensions, among the groups are real and deep, and not only because Mormons think of their religion as a "restoration" of genuine Christianity after an 1,800-year apostasy that produced both Catholic and Protestant forms of the faith. The church goes far beyond its comrades in the culture war in holding that an ideal marriage—one between a man and a woman, undertaken as a sacrament in a Mormon temple—is forever binding, with marital vows, and procreation, extending into eternity. This view of marriage motivates some of the church's most controversial public stands—the most recent being its backing of Proposition 8, the California ballot initiative to prohibit same-sex marriage.

Taken to an extreme, the peculiarities of Mormon history and belief can lead to the antigovernment conspiracy theorizing of Glenn Beck and the John Birch Society, which enjoyed support in Mormon circles during the 1950s and '60s. But the same constellation of views can lead toward -consensus-building moderation. Think of Mitt Romney's stint as governor of liberal Massachusetts, when he championed health-care reform. Jon Huntsman showed similar instincts when he accepted President Obama's nomination to serve as U.S. ambassador to China. In the words of Kirk Jowers, director of the University of Utah's Hinckley Institute of Politics and a practicing Mormon, Romney and Huntsman are typical of what happens when prominent members of the church spend time "in environments where Mormonism is simply not a part of the everyday equation." They blend in.

And therein lies the paradox of Mormonism in America today. Consider the TV and Internet ad campaign recently started by the church: a range of people describe their everyday lives and finish up with the phrase "And I'm a Mormon." Church spokesman Michael Purdy describes the ads as an attempt to downplay Mormon "otherness." The message: Mormons are just like everyone else.

Except that they're not. And it is their distinctiveness that is influencing the broader culture. David Neeleman, the Mormon founder and former CEO of JetBlue Airways, brought lessons from his church to his company, donating most of his salary to a fund for needy employees and regularly shedding his suit and tie for a flight attendant's uniform. Management guru Stephen Covey has sold millions of books translating core elements of the upstanding, upwardly striving Mormon outlook into a method for becoming a "highly effective" person. Stephenie Meyer's extraordinarily popular Twilight novels and films give vampires a Mormon makeover, with a lead character, Edward Cullen, serving as a sexy model of moral purity and chastity. And the list goes on.

Politics—the field with perhaps the greatest potential to change how most Americans view Mormons—has yet to catch up. But while national figures such as Romney and Huntsman are still reluctant to highlight their Mormon faith, other politicians are starting to see their Mormonism as a selling point. Matt Salmon is one of them. After losing to Janet Napolitano in 2002, partly because of that independent polygamy ad, Salmon, a former congressman, retreated from public life for a while. "They put signs up beneath my signs saying 'Don't Vote Mormon,'?" he recalls. "If you did that with any other religion, you'd be crucified." But now Salmon has decided to run in 2012 for his old congressional seat—and he's refusing to "hide" from his heritage. "Our Mormonism is fundamental to who we are, whether in business, politics, or our daily activities," he says. "I've come to the conclusion that I love to serve and would love to serve again. But if I have to shade over who I am and what I really believe and how I think to be successful, then I don't want to be successful."

With McKay Coppins, Andrew Romano, and David A. Graham

Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this article stated that the McCain-Palin ticket carried Utah with 78 percent of the vote. They in fact carried the state with 63 percent.

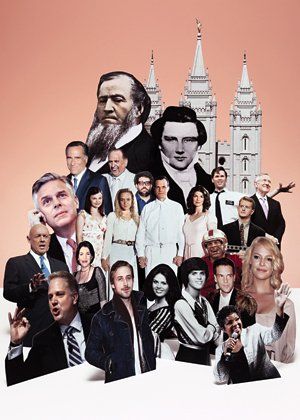

Photo Illustration by Bela Borsodi; Source photos: Joan Marcus (The Book of Mormon), HBO-Courtesy of Everett Collection (Big Love), AP (Beck, Knight, Smith, Jennings), Corbis (Steve Young, Covey, Osmonds, Temple, Heigl, Gosling, Huntsman, Labute, Monson, Brigham Young), Getty Images (Flowers, Reid, Meyer, Romney)

Key to intro graphic: From top center, left to right: 1. Angel Moroni. 2. Salt Lake Temple. 3. Brigham Young. 4. Mormon church founder Joseph Smith.

5. GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney. 6. Prophet Thomas S. Monson (current head of the Mormon

church). 7. Playwright Neil LaBute. 8. Actor Andrew Rannells playing a missionary in the Broadway musical

The Book of Mormon. 9. Harry Reid (D-Nev.), Senate majority leader. 10. Potential GOP presidential candidate

Jon Huntsman Jr. 11. The cast of HBO's Big Love. 12. Ken Jennings, Jeopardy! champion. 13. Football star

Steve Young. 14. Highly Effective author Stephen Covey. 15. Twilight author Stephenie Meyer. 16. Entertainers Donny and Marie Osmond. 17. Singer Brandon Flowers of the band the Killers. 18. Actress Katherine Heigl.

19. Glenn Beck of Fox News. 20. Actor Ryan Gosling. 21. Singer Gladys Knight.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.