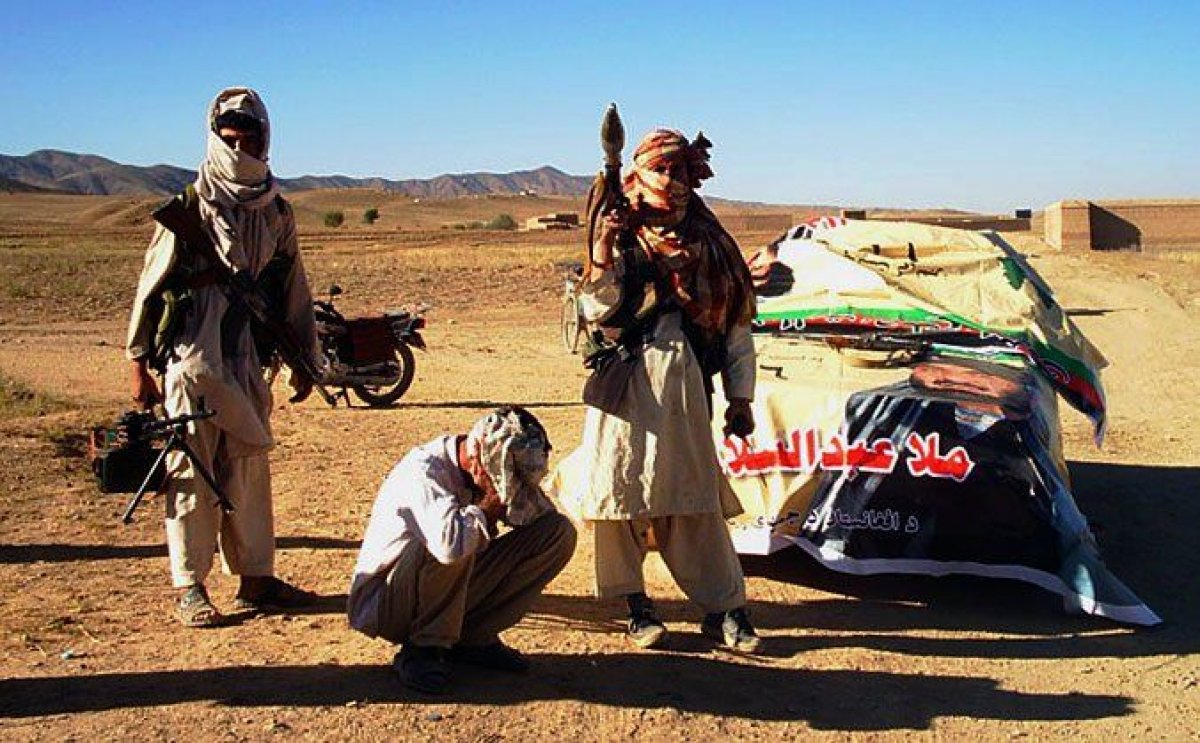

On his home ground, back in Afghanistan's embattled Helmand province, Payanda Mohammad refuses to give up his sidearm. He wore it proudly as a sign of his rank when he led a Taliban combat squad, and his family members still allow him to carry it—after they quietly and prudently made sure the firing pin was removed. They never know when he'll fly into another unprovoked rage, or when he'll experience another violent flashback to the battles he fought against U.S., British, and Afghan government forces around his home village in Nawa district, not far from Marja. It can take several people to wrestle him to the ground when he has one of his fits.

But right now the weapon is hundreds of miles away. His family made him leave it home when they sent him across the border to Pakistan for medical treatment. He and two of his cousins are sitting in a grimy hotel room in Peshawar, talking to a NEWSWEEK reporter, when Mohammad sits bolt upright on his bed and shouts: "Quick! Give me my walkie-talkie!" He grabs his mobile phone—without turning it on—and begins barking orders: "Zahid! Do you have enough weapons and RPGs? Good! Maneuver around to the right! Obaid, you make sure our bombs are primed and hidden in the right places along the canal! See that all the men are alert, so none of the English can escape!" He waits, listens, and issues a final command: "Hold the detainees until I give the next order. I will convey the results of our successful attack to our superiors." He slumps back on the bed, visibly exhausted.

His family says Mohammad has been like this ever since an American bomb scored a direct hit on his squad in July. He regained consciousness only to be told that he was the sole survivor of the blast. "He kept crying and asking God: 'Why am I not a martyr like my men? Why did I survive? What do you have against me?'?" one of the cousins recalls. Faridullah, a 35-year-old Taliban member who's been assigned to keep an eye on troubled former commanders like Mohammad, says he doesn't know when or if Mohammad will return to the battlefield. "I think he's a danger to himself and others," he says, gesturing at a nasty bruise on his face where Mohammad slugged him a day or two earlier.

Among American troops, posttraumatic stress disorder has become one of the signature injuries of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The number of service members suffering from the condition has been estimated as high as 400,000, and suicide rates in the U.S. military have at least doubled in the past decade. Yet for all the millions the Pentagon has spent on studying and treating PTSD, and figuring out ways to prevent it, no one has given much thought to whether the enemy suffers it as well.

The reasons are obvious, of course—both lack of access to patients and a quite understandable feeling that Taliban fighters don't deserve any sympathy. But the insurgents themselves say psychological problems in their ranks are bad and getting worse—to the point where it may be affecting their combat effectiveness. The question facing the Obama White House as it undertakes another review of progress in the war is whether the current U.S.-led onslaught has in fact dealt a serious setback to the Taliban, very possibly disrupting the guerrillas' momentum, if not reversing it.

The NATO push has been relentless: coalition forces have killed or captured some 350 low- and midlevel commanders in the last year, together with more than 1,000 fighters. Taliban commanders are quick to point out that those physical costs are at least partially offset by a steady stream of young recruits seeking to avenge U.S. airstrikes on their villages or the deaths of relatives who had joined the Taliban. But the losses are taking a psychological toll as well, particularly on more experienced fighters, who have endured years of combat against a vastly superior foe.

That toll is evident when talking with Helmand-province commanders like Mullah Mohammad. He's the third man to lead his unit in the past 12 months—his two predecessors were killed in action. He says he knows of at least a dozen commanders in the province who are suffering from problems like Payanda Mohammad's, including a senior commander in Nawa district who has also been sent to Pakistan for treatment after a mental breakdown. Faridullah, based on his work with Taliban combat-stress victims, estimates that well over 100 fighters and commanders in just the two provinces of Helmand and neighboring Uruzgan are suffering from serious mental problems as a result of their combat experiences. He speaks of two unrelated incidents recently in which Taliban fighters snapped and turned a weapon against their own men and friends, killing more than a dozen people altogether. "We are humans," Mullah Mohammad says. "An animal couldn't withstand the strains we are under."

That's a sharp difference in tone from insurgent leaders' accustomed confidence. "I'd say 100 percent of Taliban have suffered and seen enough death and destruction to become mentally sick," says a senior Taliban intelligence officer who covers eastern Afghanistan. "There is no Taliban member who has not suffered a big mental shock from combat, explosions, the loss of fellow fighters and friends."

Combat-related mental problems are a fact of life for just about everyone in Afghanistan, of course. According to Dr. Suraya Dalil, Afghanistan's health minister, 60 percent of the population is suffering from mental-health problems, thanks not only to the war but to the country's extreme poverty and woefully inadequate health care. "Mental illness among the people is as common as malaria," says Mullah Mohammad. "It's alarming, but not surprising, that there are so many psychologically disturbed people in Afghanistan," says Dr. Wahab Yousafzai, a Pakistani psychiatrist who runs training courses for Afghan physicians who work in provincial health-care centers. "Common people feel helpless. Death can come at any minute from U.S. and NATO forces or the Taliban."

Yousafzai's students say they're seeing a growing number of patients complaining of severe depression—and that includes Taliban. "One doctor told me, 'Everyone seems to be Taliban. So we treat anyone asking for help. We really don't know who's who.'?" No matter who they are, Yousafzai says he's encouraged that so many Afghans have begun seeing physicians about their mental-health worries. Afghans have traditionally regarded mental illness as an embarrassing curse to be kept hidden, an affliction caused by jinn and witchcraft. Sufferers needed to have the evil spirits driven out, either by the local mullah or by pilgrimages to Sufi shrines. At one such shrine in Nangarhar province, the mentally disturbed are chained to walls and trees and kept on a bare-subsistence diet for up to 40 days, if the symptoms don't stop sooner.

Sufi shrines have done little good for Yousaf Khan. He assumed command of a 10-man unit in Ghazni province in 2008 after his two predecessors had been killed. Now he's stretched out on a thin foam mattress at a Taliban safe house in Karachi, a big bag full of medicine bottles beside him. At 29 he looks weak and bloated, and has dark circles under his eyes. Although the temperature inside the room is in the high 80s, he's wearing two thick sweaters and complaining that the city is too cold. He often turns violent, according to his brother, Fida Mohammad. At night he sleeps fitfully, alternately laughing and crying. One minute he's accusing his brother of being against the jihad and not letting him return to the fight; the next minute he's announcing, "Our mujahedin have reached Kabul."

Khan barely remembers what happened to him one day in mid-2009. "I think my brain got a shock," is all he can say. His brother tells the story: U.S. aircraft were hovering overhead. Khan and two of his men took cover on one side of a mud-brick wall while three more of his fighters hid on the other side. When an American bomb struck on that side of the wall, the blast threw Khan into the air, knocking him unconscious and covering him with debris. After waking up he searched for his comrades, but he found only pieces of burned flesh and torn clothing. He was taken to his family's farmhouse near Ghazni city. He began suffering from insomnia and turned violent.

After several fruitless visits to Sufi shrines, his brother took him to a medical clinic in the Pakistani city of Quetta. A CT scan showed no brain damage. A doctor gave him pills that were supposed to calm him down, but he remained out of control. He started shouting in the clinic's waiting room: "Long live Mullah Omar and the Taliban! Death to America and the Pakistanis!" Back at home he grew so violent that his family kept him shackled for days at a time in a room apart from everyone else. Whenever they let him loose, he wandered away.

Khan's brother, a schoolteacher, quit his job to look after him. He has taken Khan on medical trips to Pakistan seven times, spending more than $3,000 in transportation, bribes to police, and medical fees, and just about exhausting the grape-growing family's savings. The brother says the Taliban have given Khan no assistance. "The Taliban don't care for the mentally ill," he says. "They help if you receive a physical wound, but not for a mental injury." He says the family is considering one final option that a Karachi physician suggested: electroconvulsive therapy. "Sometimes I cry for him," the brother says. "He was so smart, the first person people listened to on family affairs. Now he's mad. Sometimes I think he would be better off dead."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.