In America's cultural life, there are foxes, there are hedgehogs, and there is Stanley Kauffmann. He has been reviewing films for The New Republic (with one brief but significant break) since 1958. If you start counting with The Story of the Kelly Gang, the 1906 film that's generally hailed as the first full-length feature, that means he's been writing about movies for half the history of the art form.

Yet in a life marked by great dedication to one discipline, he has found time for all sorts of other pursuits: novelist, book editor (he discovered Walker Percy's The Moviegoer), teacher (at Yale and elsewhere), author of a pseudonymous Western that became a movie, and host of a TV series on the arts, for which he won an Emmy. If there's a job that involves stringing words together, Kauffmann has probably done it in his 94 years, and done it with distinction.

Kauffmann's first love, though, is the theater. Having acted and written some plays in his younger days, he has kept up a side interest as a drama critic. (That break from writing about movies came in 1966, when he had a contentious eight-month stint as chief theater critic of The New York Times.) His newly published anthology, About the Theater, collects 22 of the essays he has written during the last quarter century. Because they appeared after his final regular stint as a drama critic ended (when Saturday Review closed in 1984), the book isn't a record of several seasons of Broadway churn. They're occasional pieces, an array of insights and observations gathered during a life deeply engaged with the performing arts of the 20th century—and, now, the 21st.

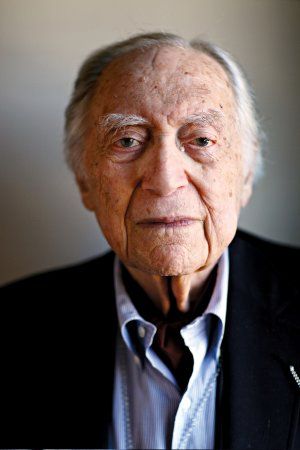

I should dispense, at this point, with any claim to strict objectivity. Since we met at The New Republic a decade ago, Stanley has become a friend. We get together now and then for tea and conversation. Nattily dressed in a jacket and slacks, mind as sharp as ever, he laughs easily, but maintains an almost courtly air. "How are you, old man?" he will say in jovial greeting, and for a moment it feels like a Howard Hawks film.

It's a testament to Stanley's gentility that on occasions like these he lets me pump him shamelessly for stories of yore. He saw his first movie (a Chaplin silent) in the early '20s, began attending Broadway shows (Blackbirds of 1927) soon after that, and can vividly describe much of what he's seen, heard, and read ever since. You don't meet many people nowadays who can speak authoritatively about Orson Welles's voodoo staging of Macbeth, or the legendary opening night of Waiting for Lefty (when Clifford Odets's radical tract led the audience to chant, "Strike! Strike!"). But Kauffmann can, because he was there. He was chanting along.

All the talk about longevity leaves him a little bemused. ("People ask how I did it," he says. "I didn't know I was doing it.") But the quality that makes his writing and his conversation so compelling isn't the mere being there, it's the knowledge he's accumulated over nearly a century of art and life. "I've never met anyone who wears so much learning so lightly," says Leon Wieseltier, the literary editor of The New Republic.

Thus, when he writes about Christopher Plummer's depiction of John Barry-more in one of the newly collected essays, he doesn't just draw on his memory of having seen Plummer's Macbeth several decades earlier—and, several decades before that, having seen Barrymore play a version of himself in the 1940 Broadway comedy My Dear Children. He cinches the review with this striking insight: "Most of the acting of our time sets verisimilitude as its sole aim. The classic actor—Plummer, in this instance—sees verisimilitude as a step along the way to qualities more spacious, daring, mysterious…that existed before us and will exist after."

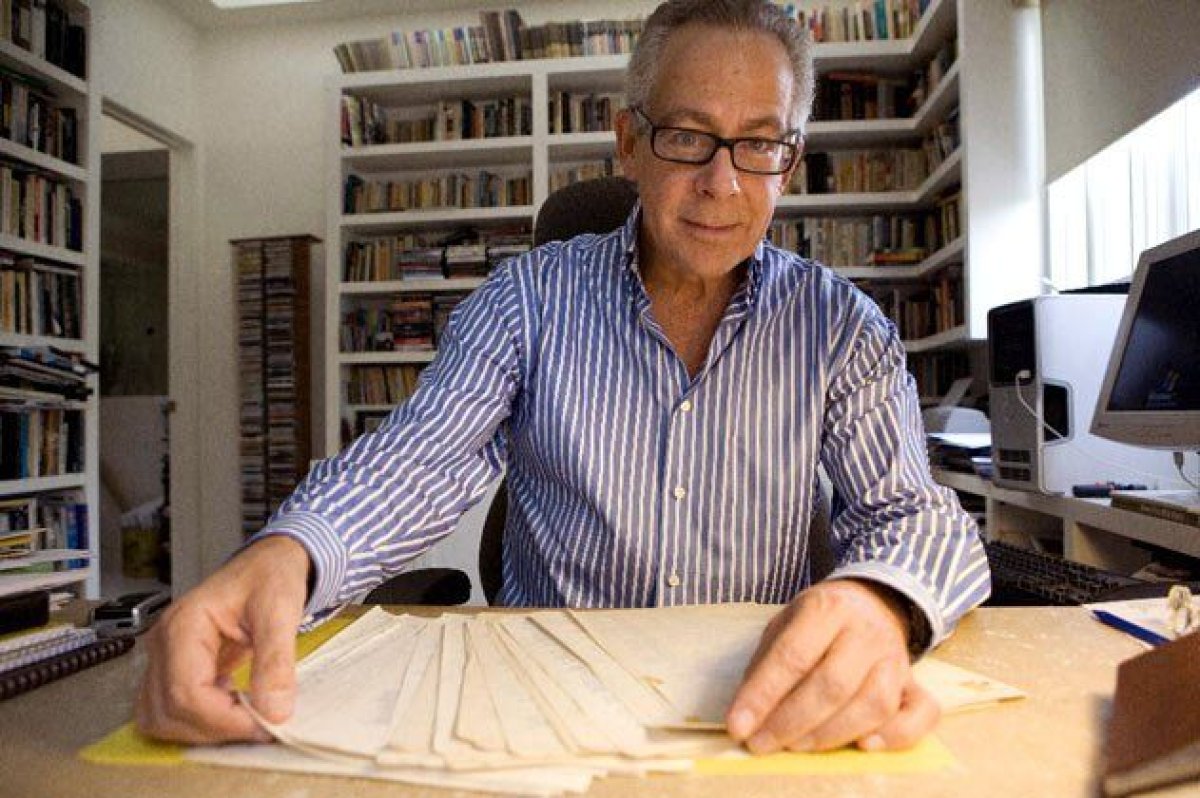

Kauffmann stopped going to plays a few years ago. Lately he's given up film screenings, too. Now studios send DVDs to his book-lined Manhattan home. He misses it, he says—the sense of occasion. And he loses the ability to meet young film people who—anecdotally, at least—don't know him as well as their elders do. (A few years ago, Roger Ebert called Kauffmann "the most valuable film critic in America" and "the one I turn to with the thought that, if we disagree, I may very well be wrong." In a recent e-mail, Ebert said that he stands by every word.)

This new routine has its compensations, though. Hollywood blockbusters, never prominent in Kauffmann's reviews, are now nearly absent. He picks and chooses among obscure independent films and even more obscure foreign work. As a reader, I confess to being sorry he didn't review Avatar: it would have been something to see the breakthrough of 3-D heralded by someone who witnessed the arrival of talkies. But he says the movie put him to sleep. "Why write about films that aren't worth my time, or the reader's time?" he asks.

Kauffmann is sanguine about time and how to spend it. The fact of being 94 makes him "slightly nervous, but grateful. And happy." He has been revisiting old books ("Evelyn Waugh, Isaac Babel—just standard names") and old films, like the early efforts of the French New Wave, whose freewheeling streak he admires more than he used to. On many afternoons, he and Laura, his wife of 67 years, host a kind of salon. Old students such as NEA chairman Rocco Landesman drop by, as do newer friends like Jeffrey Horowitz. It was because of conversations with Kauffmann that Horowitz decided to produce three obscure plays recently with his off-Broadway company, Theatre for a New Audience. According to Horowitz, Kauffmann went to rehearsals, gave notes, took an interest in everything—which is about what you'd expect someone with his broad sympathies to do.

By working so productively for so long, Kauffmann joins a select group. It includes his hero, George Bernard Shaw, who wrote provocatively well into his 90s, and America's new octogenarian sweetheart, Betty White. But as he sails into what I choose to think of as his early middle age, he remains an exception. Kauffmann hasn't just outlasted his critical compères of the Film Generation (a term he coined): as film-critic jobs have dried up lately, he almost seems to have outlived the profession. It's hard to imagine that anyone who comes after him will put together a body of writing as far-reaching as Kauffmann's, as well informed or as sympathetic. In this way, he embodies a certain humanist ideal, one that recognizes that the exploration of art is really a means of appreciating life. Wieseltier detects about him "the quality of a sage." I think of a Prospero who didn't give up his books.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.