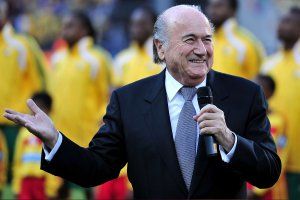

Getting to the World Cup has never been easy. Hotels go fast. Tickets go faster. The trip, prolonged for American fans by their team's advance to the knockout round, requires months of advance planning. But no amount of preparation would have eased passage to this year's contest. Visitors can thank FIFA president Sepp Blatter for a raft of unprecedented screw-ups.

Blatter, a Swiss moneyman who draws corruption allegations like a Chicago pol, oversaw several boneheaded decisions in the run-up to the tournament. Some, like selecting an abominable Shakira jingle as the theme song for a sporting event in Africa, were tasteless and inconsequential. But others, like a sweetheart ticketing and accommodation-booking contract, have frustrated both fans and local South Africans and potentially cost the host country millions that would have been spent in foreign cash.

The deal in question was with a company called MATCH Services AG, which is co-owned by the company where Blatter's nephew Philippe is CEO. MATCH reserved almost two million nights' worth of rooms in hotels and guesthouses across South Africa in anticipation of 500,000 wealthy foreign visitors. But the company also tacked on high surcharges that helped drive up prices. A room in Johannesburg that would normally cost $100 per night was suddenly going for twice that amount or more, global recession be damned. Owners of guesthouses and B&Bs who hadn't signed up with MATCH got even greedier. In April, the owner of Die Agterplaas B&B in Johannesburg tried to charge me nearly $2,000 to stay a week at her place, $1,500 more than the room is going for immediately after the World Cup, according to online booking sites. When I told her that she was gouging me, she blamed FIFA. Even $20-per-night hostels were asking $70 for a bunk bed in a dorm room.

The end result was what you might expect: foreigners, who were already paying $1,500 or more in airfare to visit South Africa, simply decided not to make the trip. Lots of people. Numbers are impossible to truly gauge because Blatter runs FIFA like one of those banks down the street from his offices in Zurich, but the best guess of Danny Jordaan, the head of the local organizing committee, is that more than half of the foreign visitors projected to show up at the tournament will instead be watching it from their sofas at home.

South Africa and FIFA both say plenty of foreigners are attending, but their numbers differ: the government says 456,000 came and FIFA, in a statement, cites 372,000 foreigners, with 97 percent of the 3,009,000 total purchasable tickets sold—though there is no way to tell how many of those tickets have actually been used. By contrast, according to Forbes, around 2 million foreign visitors came to Germany when it hosted the Cup, and all 64 matches sold out.

What's worse, some international fans had already bought pricey game tickets ranging from $80 to $160. But now they couldn't afford to use them. They directed their wrath at Blatter. On the forums of BigSoccer.com, angry fans inveighed against FIFA and its president. One commenter described FIFA as "unorganized organized criminals." There was even chatter about a class-action lawsuit. FIFA has tight security controls on transferring ownership of tickets and an impossibly opaque system for reselling them. Fans could get a refund, but only if FIFA offloaded the tickets for similar value—a big problem when foreign demand plummets and South Africans can't afford to pay the same prices as tourists.

And there was yet another snafu: most African tourists have tight budgets and limited Internet access, meaning that the few who could afford tickets to South Africa weren't likely to buy them online. Fifty thousand people from other parts of Africa were originally expected to attend the continent's first World Cup. The number now is closer to 11,000, according to Grant Thornton, an accounting and consulting firm that tracks World Cup sales. That's a paltry 2 percent of all visitors.

All of which conspired to create a righteous cock-up, as frustrated British fans might say. Less than a month before the start of the World Cup, demand for tickets was so weak that anyone could get into just about any game. Facing the embarrassing possibility of matches played in half-empty stadiums while being broadcast to an audience of billions, Blatter and his crew went into scramble mode. They converted unsold tickets into an ultracheap option (under $20) available only to locals and embarked on a fire sale to fill seats with South African fans. In this soccer-crazed country, these are exactly the people who should have been going to the games in the first place, but they generally don't factor into the corporate decision-making process in Zurich, even though they've purchased around 75 percent of the tickets.

Unfortunately, FIFA's latter-day maneuvering wasn't enough. Attendance at the tournament so far has been weak: only four of the first 11 sold out, for instance. A game on June 12 between South Korea and Greece in Port Elizabeth drew only 31,531 people in a stadium built for 42,486. On nonmatch days, towns like Port Elizabeth, Nelspruit, or Polokwane are seeing so few tourists that only the FIFA banners plastered on street corners would indicate that a World Cup is underway. And on a blustery day in Durban this week, more people were selling hot chocolate on the beach than watching Portugal play Ivory Coast on the big screen in the "fan fest" park.

The bigger issue is that FIFA's gaffes may have longer-lasting consequences. South Africa laid out well over $4 billion to build stadiums and upgrade infrastructure, and while locals are understandably delighted to host the tournament and overturn narrow-minded stereotypes about their country, reports are already rolling in about the excessive costs—the refurbishment of Soccer City in Johannesburg, for example, ended up exceeding the projected cost by more than $400 million—and fears that remote stadiums like the one in Rustenburg will be underused after FIFA leaves.

The World Cup is never the economic boon for host countries that many think it is, and FIFA, a tax-exempt organization that will bring in $2.7 billion off television rights for the tournament, has hardly been charitable. Last week, security guards at several stadiums went on strike over pay. FIFA, they claim, promised them $65 for a 12-hour shift. Instead, they received $25 from their employer, Stallion Security Consortium. Around 3,000 locals took to the streets in Durban on Wednesday chanting, "Get out, FIFA mafia!" Blatter could hardly have imagined this scenario when he invoked the spirit of Mandela at the tournament's opening ceremony two weeks ago. It's the World Cup, after all. The streets are normally filled with happy singing fans.

Luke O'Brien is a writer based in Washington, D.C. His work can be found at www.lukeobrien.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.